The Influence of Old Materialisms; or, Three Scenes of Self-Regulation

Lenora Hanson

In “Materialities of Experience” William Connelly distinguishes new materialism from mechanical materialism as well as from the idea that “everything is in flux.” In other words, new materialism is neither a deterministic nor a chaotic materialism. Instead, the organizing principle of new materialism is the “oscillat[ion] between periods of relative arrest and periods of heightened imbalance and change.”1 An oceanic style of thought has emerged from the displacement of cause in favor of oscillation indicated here. The language of new materialism, as well as much post-critical writing, displaces the problem of origins and orders in favor of oscillation, vibration, inter-involvement, correspondence, analogy, etc.2 These methods explicitly privilege relationality as an ontological category over accounts of the conditions of possibility that order relations.3 They favor a redistribution of human and nonhuman agencies over causal accounts of agency, performatively enacting that redistribution through extensive lists and network analysis.

But causality continues to haunt new materialist attempts to substitute oscillation for determinism. To be overly simplistic, in such ontologically-concerned accounts, change occurs because the nature of matter tends towards change. What Connolly calls “emergent causality” is indicative of this problem, as it suggests that oscillation is its own cause—that is, that oscillation is both cause and effect of what is always already becoming. Causality becomes a tautological circle here. In an attempt to get away from determinist or transcendental causes, which depend upon a “higher power” outside of matter, new materialism refers us to “the dicey process by which new entities and processes periodically surge into being [triggering] novel patterns of self- organization….”4 New materialism thus ends up in a tropological circle in which causality takes the structure of substitution (that of oscillation, surges, and triggers).

This paradox is, at least in part, produced by a general resistance to Marxian accounts in which determinate causality was already displaced in favor of an overdetermined interrelation between life and activity called production.5 In contrast, new materialist approaches tend to conflate an ontology of the “inter” or the relational with a history of relationality. In the latter, the relational more often than not comes into view as a limit point rather than a continual emergence. Indeed, one way to tell the history of capitalist accumulation is through the dependency of paid labor upon social, affective, and ecological relations through which capital staves off imminent crisis. Another history of the relational would need to include what Rei Terada has recently described, a long history of philosophy hinges on non-essentializing and relational epistemologies that delimit political agency, not through determinate causalities but through the terms of mutual relationality and co-existence that she reads as a logic of racialization.6 This problem of the historical is significant because it provokes a mediation or a fold in the relational, one that demands an account as to how it is—not why it is—that particular kinds of relations exert the force of the causal and agentic (a transcendental force) without recourse to actually-existing determinate causalities or centralized agencies.

Below I take up this fold of the historical through a return to the putative difference Connolly draws between mechanistic materialism and new materialism. In the following scenes, I ask what it would mean if even in mechanistic materialism, causality was always already a matter of distributed relations? That is, what if even the age of mechanical materialism—that materialism of the 18th century—was more concerned with the relational than the agential? Or with the distribution of relations rather than with the matter’s absence of agency? What if agency was only the retroactive effect of relations that were more or less stable, more or less self-regulating, more or less equilibrating? Would the problem then be to redistribute agency, or to attend to those historical constellations of relations of which causality was an effect?

Here I assemble a series of scenes in which 18th century materialism can be seen as a repressed influence on new materialism, specifically in its theorization of vibrating bodies, self-regulating cycles, and nonhuman histories. New materialist repressions of its 18th century variants are immensely useful, however, in that they trace the contours for a more dialectical account of materialism. By engaging that influence more directly, we can understand negation or forgetting, in this case in new materialism, not as an actual erasure but as a repurposing of the debris of the past that can be usefully put into practice for the present.

Scene One: Economies of the Hand

Between 1749 and 1775, an allegory of materialism circulated as follows: A child reacts to an object impressed upon his hand (“The fingers of young children bend upon almost every impression which is made upon the palm of the hand”). After this first reactive desire (“excited by the sight of the favourite play-thing”), the child continues to repeat this motion (“After a sufficient repetition of the motions…reacting to the faint recollection of that first touch”). Gradually, these external sensations become associated with the sound of words the child hears his nurse say (“the sound of the words, grasp, take, hold, &c., the sight of the nurse’s hand in a state of contraction”) giving way to the simultaneous association of reaction, desire, and language (“at last, that idea or state of mind which we may call the will to grasp, is generated”). The culmination of this process is not a willful, voluntary subject, but a subject “secondarily automated,” one habituated into a cycle of socially-accumulated associations that he performs involuntarily.7

This operation is an economic one, a division of labor between organs (hand) and environment (nursery) that runs on an exchange logic. In this model, the will is a product of substitution, the economizing exchange between parts that are unified in the abstraction of time made visual. This visible hand constellates the mechanical and the sensible in 18th century materialism, suspending the body of the child somewhere between Foucault’s taxonomically-crazed Classical episteme and the 18th century. It depicts a body economic, one whose division of labor depends on its spatialization. Broken down into successive units, each instance is equivalent to the next on this highly visualized plane of description. Not just a physiology of the invisible hand, as free trade or the commodification of labor, here an innate equivalence, a natural price of sorts, is born out in a body where no variation affects the whole. Circulating through this scene is the relation between need (“excited by the sight of the favourite play-thing”) and the exchange of association as the play of equivalence, “necessity [is] the measure of equivalences.”8

But the substitutability—of part to whole, from part to part—in the associationism above is not mechanistically determined. It is a movement, a motion, an iteration. It is an oscillation between an arbitrary event (“The fingers of young children bend upon almost every impression which is made upon the palm of the hand”) and habituation (of domestic space, of linguistic signs, of descriptions of self-regulation). Equivalence is the ongoing mediation between the contingent and the historical; like a sign “it is arbitrary…because is totally subject to history.”9 Spatialized in the body, set in the backdrop of the nursery, history is enclosed in a cycle of the self-same—not a sameness predetermined mechanically but one continuously impressed into a motion.

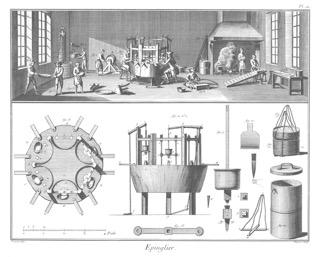

Diderot and d’Alembert,“Pinmaker,” Encyclopédie (1765) They are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants, and thus without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society… (Adam Smith, Theory of Moral Sentiments 250)

For Jordy Rosenberg, such scenes of self-regulation mediated the disappearing profits of capital investment and the transatlantic slave trade in the 18th century. The dialectic between the subject and the social tolerates excess, with the faith that cycles of liberal sociability will correct for it: “One senses one’s own processes of cognition and sensation and, in sensing them, senses the social whole.” Thus, excess—or what Rosenberg calls enthusiasm—comes to be the test case of the “ideal of British ‘equal’ exchange in the eighteenth-century labor and commodity markets,” as well as the way to distinguish between those subjects who are and are not self-regulating.10 The scene of the habituated hand above, conjured by the scene of the bourgeois nursery, shows us that mastering enthusiasm—the desire for the object—operates through the sympathy that individual parts have with the social whole. [Never mind that this mastery is supplementary, substituting the nurse for the mother, the nursery for the social, habit for desire.]

But self-regulating economies—of bodies, of things, of capital—did not always appear self-originating. In some instances, this series of substitutions is revealed as an act of force, more visible when scaled up from the domestic space to a map of empire. For instance, Joseph Priestley’s 1769 A New Chart of History orders the history of empire in a linear fashion not because this is how history actually works, but in order to train the eye and the mind to operate in a uniform and balanced manner. The linear, according to Priestley, facilitated understanding while avoiding the potential error of sensory excess. The linear representation of time is a physiological imposition, a disciplining of a kind, in which history creates a cognition that will “flow uniformly, from the beginning to the end…flowing laterally, like a river.”11 [In other words, whether line of empire or assemblage of matter, nursery setting or garbage pile, sympathy is a scene of force.]12

Joseph Priestley, A New Chart of History(1769) A history in which “events hung loosely suspended like so many insect bodies sucked dry” (Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, I2/6)

The nursery scene suddenly appears more like a positing of origins, an act of force inscribed onto the body, than a description of sympathizing, self-regulating habits. But what, exactly, is being ordered here, imposed upon? What, in other words, is being written over, remade palimpsestically?

Something like a memory. In 1749, David Hartley’s Observations of Man puts it the following way:

if a single sensation can leave a perceptible effect, trace, or vestige for a short time, a sufficient repetition of a sensation may leave a perceptible effect of the same kind, but of a more permanent nature; i.e., an idea, which shall recur occasionally, at not long distances of time, from the impression of the corresponding sensation.13

The self-regulating economy of bodies is not originary; equilibrating oscillations are not auto-originating. The “effect, trace, or vestige” is the condition of possibility for the corresponding sensation and its sensible economy. It is the not-yet corresponding, the vestige of an-other sensation. This means that there is scene before sympathy, an exteriority to the enclosed automation of the hand. The trace is the “constitutive exteriority” to what Benjamin described as the “natural process…the cycle of the eternally selfsame” that is bourgeois history.14 A trace is a vestige—what is left over is by definition a wrench, an excess—in the economic representation of the body’s division of labor.

The trace makes correspondence—like history, like automation—a retroactive imposition (of force?).15 Correspondence originates in a singularity that survives, in the temporal rather than the self-same. In this basic blueprint of the associating, economic body, in the first instance there is a singular, spectral event. That non-identity suggests something of a repression, an unconscious in which non-correspondence resides. If correspondence indicates the economic telos of a sensible body, the identity of parts achieved through equilibrium, then the trace escapes elsewhere. These origins are spectral, leaving the trace of another temporality hidden in the body, stored in the “positive unconscious” of the hand.16

The specter of the bourgeois nursery is found in the etymology of theft in the 18th century, which also finds itself imprinted in the hand. Patrick Colquhoun, creator of the first modern police force on the docks of London, referred to theft as pilfering.17 Pilfering, as one etymology dictionary has it, derives from the “palm of the hand.” This same dictionary also has it as meaning “to have signified to peel or skin.” Cant (or slang) dictionaries that promised access to the language of urban criminality catalogued “light fingered” as the term for thieves. And Priestley, the writer of linear history, recommends garnishing the wages of the working poor in order to discipline them into longer working days, concluding this recommendation with the specter of a hand in the act of theft: “[the common people] have no sense of shame in being supported by others, and are too ready to pilfer, though they have not always the courage to take by violence.” A vestige peeled back from the automated hand, this genealogy of pilfering traces an excess to the enforced equilibrium of labor’s division.18

William Hogarth, The Idle Prentice (1747)

Hovering always in the potential state of pilfering (pilfering is a transitive verb and to that extent does not need to take an object, can always remain a specter), these scenes put our hands into a dialectics of sensation rather than a cycle of the sensible self-same. Uncovering an uneven accumulation of “effects, traces, and vestiges” in the palm, at the origin of allegories of correspondence, these hands bring into view differential economies of the body. They distill a memory of bodies that did not go into the grid of the division of labor, of equilibrated bodies, of automated sensibility.

Vibrating bodies are crossed by the pilfering, the idle, the crimanal(ized)—not opposed to each other but in a dialectical relation. Within this trace structure, self-regulating economies of bodies can only be the site of a wish-repression: self-regulation is the repression of its material condition of possibility. It is the wish for what could be harmonious and self-regulating in the body, but that, for now, only represses a history of accumulation on its surface. A self-regulating physiology encases, in the negative form of the depiction above, an impression of the refusal of labor in the hand of a thief.19

Scene Two: Accumulation Impressions

In The Order of Things, Michel Foucault proposes a constitutive asymmetry within the advent of historicity, what he refers to as a “series of accumulations.” This asymmetry was schematized in the knowledge of the living organism: on the one hand there was the “great, mysterious, invisible focal unity” of biological functions and on the other the “biological being [that] becomes regional and autonomous,” making species “totally distinct from one another.” On the level of organic structure, one finds relations of “co-existence, of internal hierarchy, and of dependence.” On the level of species (what Foucault strangely never references as race although the term was used frequently in the very writing Foucault cites) “living beings…must group themselves around nuclei of coherence which are totally distinct from one another.”20 In an 18th century episteme, then, the living emerges as what is common to all and what creates a caesura that divides absolutely. Onto the commonality of biological function was mapped the absolute divisibility of self-enclosed species. Central already to this model, which in many ways provide the initial schema that would later be articulated as biopolitical state racism, is a non-contradiction between the corresponding and the divided.21

Mediating this asymmetry was the equilibrium any living organism was capable of establishing with its environment. A new order of things emerged in which absolute distinction was predicated upon the self-regulating totality of the living and its milieu. The asymmetry that shattered the knowledge of life into the common (comparative anatomy) and the incommensurate (species/race) redistributed hierarchies of the living through the enclosures of equilibrium.

While for the Foucault of Order this mediation of asymmetry and accumulation remains confined to the epistemic, the equilibrating operations of the living he describes provide the coordinates for capital accumulation in its biopolitical and ecological mode. As Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt suggest, the “crude grasp” of “a capitalist economy fueled by automatism…is devoid of any economic measure or principle.”22 For them, it is because we (humans) have “internalized this principle of self-regulation” that we are the condition of possibility of capital accumulation. The latter sustains itself through the auxotrophic nature of the living and its continual modulation through relations with and dependencies upon others, as “a living being that depends upon specific associations with others because it is not metabolically autonomous.”23

In other words, accumulation spaces out its time through reproduction. We can understand this process through what Jason W. Moore characterizes the law of value ecological terms. There the non-identity between paid (productive) and unpaid (reproductive, social, ecological) labor defers the imminent tendency of the rate of profit to fall in a capitalist economy.24 Reproduction functions as the “constitutive exteriority” to production, the outside or the colonialized frontier that provides an equilibrating force. This outside is continually brought inside, recycled and circulated, for the purposes of stabilizing production, but always in a non-identical relation that unfolds in the space and time of colonialism. Here again asymmetry organizes and distributes the corresponding capacities of the living. Moore’s re-reading of the law of value highlights capital accumulation as a dialecticizing of the self-regulating and the exhausting, the reproductive and the dominating.

In other words, accumulation is the asymmetrical ordering of equilibrium. But what a general analysis of capital accumulation leaves to the side is how this non-identity between the relations of re/production manifest in the real abstraction of racialization. Daniel Nemser usefully describes such a process as the ordering of the “complex assemblages” that emerged in new classificatory systems of the living in the 18th century: “The shift away from ‘things themselves’ to complex assemblages…ma[de] possible a new theory of the human body and specifically of racialized life framed in a global register.”25 The non-identity, or what I called before the asymmetry, of capitalist accumulation is also the accumulations of these differentials in the embodied distribution of race.

Alexander Humboldt and Aime Bonpland, “Tableau Physique” (1802) “Vast submarine fund, in which all cultures, all studies, all proceedings of mind and will, all social uprisings, all struggles are collected in a formless mire…The passional elements of individuals have receded, dimmed. All that remains are the givens of the external world, more or less transformed and digested” (Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project)

Accumulation is not strictly an epistemic phenomenon of historicity, then, but is a sensuous, physiological asymmetry that leaves traces of the cycles impressed into the living. These traces are records of the radical asymmetry inscribed into bodies, what Foucault refers to as the erasure of genealogy as the progress of history, what Marx described as the history of primitive accumulation written letters of blood and fire. The accumulation-through-asymmetry that schematizes living things in the 18th century assumes its concrete form, not as Benjaminian arcades, as commodity fetishes, or as architecture but as ecology, colonies, and race.

The traces impressed by these cycles are also seams in which the knowledge of resistance and revolt, what Kluge and Negt call the obstinacy of history, is distributed. If accumulation is a temporality that is specific to the living, it is because the living holds the time of the past—that it is impressed with the traces of asymmetry. Thus the living is a product of historicity, which is to say of the accrual of the past (what Foucault will later translate into the inscribed body of genealogy). Here the living, rather than the commodity, is “the material in which traces are left especially easily.”26

But these risk disappearing in ontologies of recent post-critical turns that make the equilibrium of the living readily available over a dialectal reading, in which spatialization and transience mediate its immediacy. Such methods suggest that: “present experience and…original event are the same thing. It is as if we share our being with the past (taking the same ontological status) and so receive knowledge about the past (overcoming the problem of epistemology). Ontology and epistemology are fused.”27 History is fused not with the conditions of knowing, but the abstract substance of knowledge. The relation between past and present is flattened out—made absolutely continuous—in order for the past to be made immediately available to “present experience.” In other words, history is made entirely into a matter of thought and its ability to make equivalent, to create correspondence.

But if the above genealogies of correspondence reveal anything, it is that such operations of consciousness are a site of desire, the “wish image” of the “not-yet-existing” (the trace) of a “utopian imagination that need[s] to be interpreted through the material objects in which it [finds] its expression.”28 The wishfulness for sensible, self-organizing bodies to exist in a continuous present, through the fusion of the mental and the historical, the ontological and the epistemological, neglects the difference within accumulation that equips us with a language for understanding how fusion, interdependence, inter-involvement are organized differentially. Locating such bodies within this gap preserves the possibility of memory.

Treating the relational as a history of a “series of accumulations” would mean mining the seams of uneven and irregular production of violence, the disjunctures which allow for the crucial possibility of drawing from histories and relations that had to be erased in a particular ordering of relationality. Ontologies of the immanently fused, the interrelated, the analogous flatten out the trace of that ordering, risking another erasure of the conditions of possibility of what Benjamin called remembrance.29

Scene 3: The Mole and the Dream

And when [the sleeper] wakes and wants to tell of what he dreams, he communicates only boredom…For who would be able at one stroke to turn the lining of time to the outside? Yet to narrate dreams signifies nothing else.30

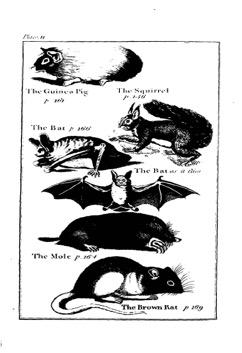

A 1792 English edition of Buffon’s Natural History gives the following entry:

The Mole has eyes so small, and so concealed, that it can make but little use of feeling. In recompence Nature has supplied it with an ample portion of the sixth sense. Of all animals the mole is the most profusely furnished with generic organs, and of course with the relative sensations…its little paws, with five claws, are very different than other quadrupeds, and nearly resemble the hand of a human being.31

Relatively lacking in those senses that make other animals suited to the immediacy of their surroundings—of the senses that provide instinct—The Mole relies on “relative sensations” and a “sixth sense,” a second nature perhaps, to make his way beneath the accumulated earth.

Incapable of seeing in front or behind him, he shares this constitutive lack—and auxotrophic relations—as well as “the hand” with the human being. This mole-human hand gestures to the mining work that must be done in order to turn the dreamtime/spacetime of accumulation inside out. It is a reminder that we live within and beneath the enclosures of autonomy and self-determination that emerged in the 18th century, but also that “‘the role of bodily processes’” are seams “around which ‘artistic’ architectures gather, like dreams around the frame—work of physiological processes.”32 This hand of the mole-human operates underground because history is not immediately available, because experience is not immanently interrelated. These hands know that pilfering is necessary because the resources for reproduction are not so readily available on the surface.

Long a favored animal of revolutionary thought, for Kluge and Negt the mole is significant not for its lack of sight per se, but because its life underground accumulates a history of traits produced alongside of capital accumulation. Second nature in this sense is not an alienation or a fall, but a store of memory-capacities waiting to be redeemed. The natural history of the Mole is “a secondary, black-market economy, where, isolated from the authority of the ego and capital’s logic of valorization, repressed and derealized traits take on an intransigent life of their own.”33 The obstinacy accrued in the bio-physiological processes constitute a subterranean field of acts and traits within the history of life, labor, language.

The problem, then, is to know how these traits, these seams, these dreams have been/will be organized and mobilized. This knowledge is a genealogical one, which is to say that it appropriates and activates the contingencies of the past in a struggle over the past. In this sense, a dialectical method shares a speculative and retroactive nature with primitive accumulation.34 If primitive accumulation is the mythical remaking of a contingent past into the necessary-present, then, in Marx’s own words, dialectical “research” also “has to appropriate the material in detail…to trace out their inner connection” so that “if the life of the material is reflected back as ideal, then it may appear as if we had before us an a priori construction.”35 The point is not to locate a continuity or sameness with the past, or to make the dead into the present. Indeed, to establish the relations of history on such terms is to enact further erasures, repressions. In Benjamin’s adaptation, the affirmation of a retroactively constructed history activates what has been lost to meet the demands of a contingent present. It is to carefully (Foucault says rigorously) trace materials for memories of what had to be undone for the present to be made, in an act that undoes the ontology of sameness. It is to locate material impressions that have the force of the originary, as the what is not-yet that has left its trace behind us.

The potential of this “as if” was theorized by Benjamin as a kind of psychic architecture—the dream. In Benjamin, accumulation gives way to cycles, too. But these cycles are structured like dreams, encasing traces of pastness in the “originary entwining of nature and history [that] pointed to a duplicitous origin and to originary transience, which not only corroded the assumption of primary substance or arche but also took leave of the metaphysical conception of nature as originary immediacy.”36 No matter how natural, how habitual cycles of accumulation might appear, they are continually disjointed by traces of transience. It is because of this that the material infrastructure of the present entwines destruction and remembrance, a repression and a wish. Dreams provide the connective tissue in which physiology meet infrastructure, where accumulation fails to erase its traces in correspondence.

Not for nothing, then, does the text that gave us the self-regulating body and hand at the beginning also note that “The wildness of our dreams seems to be of singular use to us…For if we were always awake, some accidental associations would be so much cemented by continuance, as that nothing could disjoin them; which would be madness.”37

Dreams are those associations expelled from the waking, self-regulating body. They are the material impressions that accrue within and alongside of it. Manufactured in the daylight, dreams are repressed and archived as nighttime materials, as the trace of differential associations and constitutive exteriorities through which accumulation occurs. Dreams, then, are the material impressions of an incommensurability that accrues between the body and habit, the asymmetry that structures reproduction and productivity. This eighteenth-century distribution of dreams as a madness, or a quasi-outside, generated by the same material process as that of self-regulating association offers a critical rejoinder to what I called above the “wish-repression” of self-organization. It models a self-regulating process that is organized through that which exceeds it (in this case dreams, but in the above scenes we can also say theft and unpaid labor, or the asymmetry of reproduction within capital accumulation). Against the causality of oscillation, dreams remind us that the problem has never been a purely determinate causality, or linear cause and effects, but of an accumulation that constantly fractures such space times. A materialist account of change, or of oscillation, thus requires an understanding not of determinism or linearity, but of the spectral and uneven way in which the future is continually drawn into the past, and the past into the future. Joshua Clover describes this time as the poetics of capital accumulation, as that uncanny “the future anterieur” in which “value ‘is’ not immediately, it only ‘will have been’.” “The task of dialectical analysis,” he continues “is not to discover a new cause elsewhere, but to see moments as both cause and effect, even as the process unfolds temporally.” In other words, we may not need new accounts of causality, but better accounts of how unfolding, one might say oscillation, operates through non-linear fixes. But we can also say that the task of dialectical analysis is to recover those pasts that were necessarily rendered non-causal, those constitutive exteriorities or specious associations of “madness” that have been necessary to that unfolding of accumulation.38 In other words, the task is also to remember that history holds counter-accumulations. Without such a dialectical, which is to say historical, materialism, materialism has neither a past nor future, only a continually oscillating present from which we will never escape.

Notes

Lenora Hanson is an assistant professor of English at New York University. Her academic work attends to the history of figuration, political theory, and the life sciences from the late Enlightenment to British Romanticism.

William Connolly, “Materialities of Experience,” New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics, ed. Diana Coole and Samantha Frost (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010), 179.

Anahid Nerssessian recently elaborated connections between new material and post-critical methods in “What is the New Redistribution,” PMLA 132.5 (2017): 1-2.

A perfect example of this is Connolly’s description of Foucault’s notion of disciplinary power as a “rich history of inter-involvement that sets the stage for experience.” Connolly, 187.

Ibid., 179.

Andrejz Warminski puts the matter of Marxist mediation the following useful way: “In short, life overdetermines consciousness—it is made up of contradictions and a negativity, call it, that cannot be reduced to (i.e. mediated, sublated, into) one simple, determined negations…life is not a given, positive fact but rather produced by the labor of human beings who constitute themselves as human in this history of material production; whereas consciousness is the (historical, material) relation of these human beings first to nature and then to other human beings—a relation which is historical and material because it is one ‘mediated’ not by knowing (and all the determinations that come with it: subject and object, truth and certainty, in itself and for itself, and so on) but by the historical materiality of relations of production.” Ideology, Rhetoric, Aesthetics, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), 101-102.

Rei Terada, “The Racial Grammar of Kantian Time,” European Romantic Review 28.3 (2017): 267-278.

This scene comes from Joseph Priestley’s 1775 Hartley’s Theory of the Human Mind, on the Principle of the Association of Ideas with Essays Relating to the Subject of it. But it is copied directly from David Hartley’s Observations on Man, the text that popularized vibration as the material basis of ideas, will, and habit in the 18th century. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, (CW115461839): 32-33. This scene resurfaces in the “Fourier” section of The Arcades Project, where Benjamin writes that Fourier’s conception of phalansteries as “explosions” “may be compared to two articles of my ‘politics’: the idea of revolution as an innervation of the technical organs of the collective (analogy with the child who learns to grasp by trying to get hold of the moon), and the idea of the ‘cracking open of natural theology’.” Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, Trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, (Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard, 1999), [W7,4].

Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Random House, 1970), 222.

Jonathan Culler cited in William Keach, Arbitrary Power: Romanticism, Language, Politics (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2004), 10.

Jordana Rosenberg, Critical Enthusiasm: Capital Accumulation and the Transformation of Religious Passion, (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 46, 62.

Joseph Priestley, A Description of a New Chart of History, Containing A View of the principal Revolutions of Empire That have taken place in the World, (London: Joseph Johnson, 1771), 8.

In the first chapter of Vibrant Matter, Jane Bennett offers the example of trash as an assemblage with “thing power,” that is “not restricted to a passive ‘intractability’ but also included the ability to make things happen, to produce effects” with her. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010), 5.

David Hartley, Observations on man, his frame, his duty, and his expectations, 2nd ed. (London: Joseph Johnson, 1791), 57.

Weber describes constitutive exteriority through language, as “the mediality that separates from itself, and yet…in doing so establishes a relation to itself as other.” Benjamin’s –abilities, (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2008), 197.

“Correspondence” denotes a “relation of agreement, similarity, or analogy” but in its pre-English etymology, “correspond” was also used to “express the action or relation of one side only,” as in the sense of “epistolary correspondence.” Both origins are implied in the passage above. The trace evokes an uncertainty of arrival and deferral (a short time) associated with the promissory nature of writing. It is from this uncertainty that the correspondence of different sensations ensue. Oxford English Dictionary, 2014, Online.

In the sense that Foucault used it, as what eludes consciousness but is part of the shared rules of discourse.

On Colquhuon’s career, see Peter Linebaugh, The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century, (New York and London: Verso, 2003): 402-442.

This specter could be more generally considered through the lens of Sylvia Federici’s elaboration of primitive accumulation, as those “previously accepted practices and groups of individuals that had to be eradicated from the community, through terror and criminalization” that haunts the emancipation of wage labor, or the precondition of the division of labor in the primitive accumulation of gendered labor. See Caliban and the Witch, (New York: Autonomedia, 2004), 170.

We might say, echoing Adorno, that the self-regulating, as disclosed in Hartley and Priestley, is a wish, “because its potential is not yet realized,” and that the trace is a memory, “because its desires were never fulfilled.” The challenge, then, is to not to erase the distinction of these moments in an ontology of interrelation or correspondence, but rather to see how their crossing opens up a transience that remains promissory.

Foucault, 273, 265, 269, 273.

While this asymmetry between what is analogous (function) and what cannot be compared (species) is first elaborated as particular to the 18th century concept of living things, these terms resurface in Foucault’s concept of the biopolitical hold over “man-as-species.” In that latter field of power, it is “control over relations between the human race…insofar as they are living beings, and their environment, the milieu in which they live” also creates the absolute distinction of which populations can be abandoned to die. That is, the asymmetry immanent to life in an 18th century episteme later reappears as the absolute caesura made from within populations. Even this notion of death as what is within life first appears in Foucault’s analysis of Cuvier and species thinking. This continuity suggests a contamination of epistemes that Foucault tends to keep separate: namely, life in a medico-disciplinary mode and life in a biopolitical mode. In other words, life in its racialized form appears at the modern origins of living things, and not strictly with the emergence of the nation-state’s concern over race as what “reproduces itself uninterruptedly” within populations. The fact that Foucault only directly considered the latter as an operation of racialization opens up a major gap what are, in fact, shared terms of the emergence of life in the 18th century and the racism of biopolitics.

They continue: “While machine capital does not observe any inherent limits or proportions…living labor, by contrast, always follows principles of measure. It possesses a sense of harmonious balance that capital lacks.” Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt, History and Obstinacy, ed. Devin Fore, trans. Richard Langston (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press/Zone Books, 2014), 85.

Ibid., 94.

Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the web of life: ecology and the accumulation of capital, (London and New York: Verso: 2015).

Daniel Nemser, Infrastructures of Race: Concentration and Biopolitics in Colonial Mexico (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2016), 162. This recognition of differentials was widespread in 18th century writing on the global. For Adam Smith, a future global equilibrium of power was latent within the rampant inequalities of global circulation in the 18th century. In The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon’s seems to suggest that the horizontality of liberal, democratic governance depended upon the radical unevenness of colonialism, in what Peter DeGabriele calls the “blind domination characteristic of the sovereign relation…displaced into the relation between the domestic and the colonial.”

Benjamin, The Arcades Project [I5,2].

Devin Griffiths, The Age of Analogy: Science and Literature Between the Darwins (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), 26.

Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project, (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1991), 115.

Markedly absent from such analyses, as I hinted at briefly in the introduction, is an account of how some relations come to be privileged or maintained within systems, networks, or assemblages. In part, this strikes me as a result of the wholesale abandonment of a Kantian framework, at the center of which was an engagement with conditions of possibility and the law-like nature of our understanding of natural phenomena. To maintain such a framework is not to take refuge in an anthropocentric subjectivity. It is, rather, to address the deeply nonhuman, which is to say transcendental-historical, structuring of our forms of relationality. Kantian conditions of possibility ask us to think possibility as what enables and limits at once, and thus as a principle that, while undetermined, is effectively like a law. That is, conditions of possibility present an indeterminacy or contingency of relations that nonetheless put organizing rules into play. In this sense, conditions of possibility are always about a memory of what is inaccessible but that continuously haunts the present through a lawlike ordering.

Benjamin, [D 106].

Georges Louis Leclerc Buffon, Comte de. Buffon’s Natural History, abridged. Including the history of the elements, – the earth, … Insects, – & vegetables. Illustrated with great variety of copper plates, … In two volumes, Volume 1, (London, 1792) 164. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Gale. New York University.

Benjamin, [O,8].

Devin Fore, “Introduction,” History and Obstinacy. Ed. Devin Fore. Trans. Richard Langston. (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press/Zone Books, 2014): 35.

Marx suggests how contingent and non-linear the development of industrial capital was when he writes: “the rise of industrial capitalists appears as the fruit of a victorious struggle both against feudal power and its disgusting prerogatives, and against the guilds, and the fetters by which the latter restricted the free development of production and the free exploitation of man by man. The knights of industry, however, only succeeded in supplanting the knights of the sword by making use of events in which they had played no part whatsoever.” Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, 2nd edition, Trans. Ben Fowkes, (London and New York: Penguin Books 1990): 875.

Marx cited in Benjamin, [N4A,5].

Beatrice Hanssen, Walter Benjamin’s other history: of stones, animals, human beings, and angels, (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1998), 16.

Priestley, Hartley’s, 223.

Terada argues for a minimal causality through which the necessary relation of the social is established. Her argument pertains to Kant specifically, but is relevant more generally for considering the tenuous construction of the relational through the space time of either succession or simultaneity. Causality, in her account, was significantly constructed by Kant as a relation, of reciprocity or co-existence, that accommodated the dynamism of unevenness or, perhaps, development, but could not accommodate non-relation: “[Kant’s] architectonic offering to the analytic of race is to create for society’s already present real abstractions of universal equivalence, spatiotemporal conditions that ensure that there is nothing else that can count as known. Rendering the uneven availability of bodies to one another into a principle of ‘co-existence’ that must be ethically policed, but cannot be rejected, is an operative part of the analytic of race…As much as assertions of essentialism, assertions of ‘inherent’ minimal reciprocity are [also] important components of racism… (“The Racial Grammar,” 275-76).