Whimsy, the Avant-Garde and Rudy Burckhardt’s and Kenneth Koch’s The Apple

Daniel Kane

Part 1 - Alice throws my shirt onto the cabin roof

‘Little Fawn-like Alice’ or, more simply, ‘Loofah’ is what my friends and I used to call Alice when we were undergraduate students at Marlboro College back in the late 1980s. Because Alice resembled Tin-Tin (sexy) and was tremendously intelligent and funny, I considered myself one of the luckiest guys around when she consented to become my beloved after months of often desperate courtship on my part.

We moved in to a cabin in the middle of the Vermont woods, and tried our best to live and love together. One summer’s day we drove down to Brattleboro to go shopping. On the drive back to the cabin I took my shirt off. As we pulled up to the cabin, something happened that has resonated with me ever since…something I think about constantly even though it happened over twenty years ago now…this is how Alice recalls it:

You were wearing that horrible mustard-colored misshapened cotton mock turtle neck you wore every fucking day that made you look green and homeless. You had just gotten back from Czechoslovakia. I was driving and you were next to me. It was starting to get hot and you took off the shirt in the car and put it between our seats. We pulled up to the cabin. I grabbed the shirt as we were getting out of the car and tossed it onto the roof of the cabin. The roof was flat so once it was up there you couldn’t see it, and there was no reason to think it would come back down. You asked me what the hell I was doing. I said it looked like shit on you and I was saving you from yourself. You looked at me like you might be seeing me for the first time. You were shocked, but you actually laughed.1

Yes. I laughed. I loved Alice for throwing that shirt onto the cabin roof. You see, I loved whimsy. I loved anything that even hinted at the whimsical. Alice loved whimsy—Alice was whimsical. She was the kind of woman who, when I asked her once what she thought of a particularly bad movie, spat out dead! dead! death! while kicking my knee gently.

Whimsy keeps you on your toes.

A whimsical action or gesture is never cute—it is too active to be reduced to cuteness, committed as it is to deflecting goals, refusing closure, scorning the certainty of ideology, denying cuddles in favor of surprise kicks. What happened between me and Alice that summer day illustrates what I mean. In our case, her whimsical decision to throw my shirt onto the roof of the cabin was to force me to fundamentally question the very standards I used to mark sartorial value. Why did I think the shirt was OK in the first place? The implications of that problem are far-reaching, as they call into question the mechanisms that decide why we like one thing as opposed to another. If I was wrong about liking that shirt, what else was I wrong about liking? What art, what music do I like that I should I not like? What are the signs of my bad taste?

Perhaps even more importantly, Alice’s gesture also made me aware that the very act of taking off my shirt in the car was a kind of a macho move. It is almost always men who feel entitled to take their shirts off at the height of summer. Standing outside the cabin shirtless, I suddenly felt vulnerable, naked, even as I remained amused. I did not feel strong. Whatever authority I had as a man who felt at liberty to strut about topless was shaken. I was absolutely jolted into presence.

Part 2 – ‘I would write on the lintels of the door-post, Whim’

Whimsy is good at stepping in and shaking surety about. The etymology of the word reveals qualities of resistance, bounciness, suddenness, disorientation, unexpectedness. According to the OED, the first known use of the word in writing is in Ben Jonson’s Volpone.2 Whimsy in this case is used by the character Mosca to describe a feeling that is at once profoundly satisfying and threatening to exceed his control:

I fear, I shall begin to grow in love

With my dear self, and my most prosperous parts,

They do so spring and burgeon; I can feel

A whimsy in my blood: I know not how,

Success hath made me wanton. I could skip

Out of my skin, now, like a subtle snake,

I am so limber3

Later uses of the word continue to play upon the surprise factor of whimsy as that surprise is predicated on affection. For example, Edmund Gayton proclaims in his Pleasant Notes upon Don Quixot (1654) ‘I love Toboso, and I know not why, Only I say, I love her (whimsyly)’ (O.E.D. 2014). Whimsy is discombobulating, disorientating. ‘I ha got the Scotony in my head already’, wrote Thomas Middleton and William Rowley around 1627 in their play The Old Law, adding ‘The whimzy, you all turne round’ (O.E.D. 2014). I especially adore later uses of the word, including N. W. Wraxall’s dismissal in 1775 of a building as whimsical precisely because a large part of it served no particular function; ‘It may just as well be called an European structure, where whimsy and caprice form the predominant character’ (O.E.D. 2014).

American uses of the word and variations thereof include Thomas Jefferson’s insistence that Plato used Socrates as a front for his own wandering wonderings; ‘Plato, who only used the name of Socrates to cover the whimsies of his own brain’. Whimsies in the brain mean a thought never stops moving, never adheres to the fantasy that taking a rational, systematic approach to uncovering a mystery or examining a question might ever lead to something as final and resolute as total understanding. Whimsy does not love wisdom but refuses its authority by insisting on play, fancifulness, and drift.

This is not to say that whimsy does not contain within it a provocative charge, as I hope my story about Alice throwing my shirt onto the roof illustrates. Indeed, one of my favorite uses of a variation on the word ‘whimsy’ is in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s seminal essay ‘Self-Reliance’ where Emerson famously questions the value of charity. ‘Your goodness must have some edge to it,—else it is none. The doctrine of hatred must be preached as the counteraction of the doctrine of love when that pules and whines. I shun father and mother and wife and brother, when my genius calls me. I would write on the lintels of the door-post, Whim. I hope it is somewhat better than whim at last, but we cannot spend the day in explanation’.5 I love the way the final two sentences cannibalize each other. Playing the part of the radical iconoclast, Emerson insists on the sanctity of his own agency and instinct even if they fly in the face of liberal convention. And yet, just as soon as he makes that move he casts doubt on his own proclamation—‘I hope it somewhat better than whim at last, but we cannot spend the day in explanation’. The implications of Emerson’s stance here are far-reaching and unorthodox:

[According] to the Old Testament, writing on the lintels of the door is something you do on Passover, to avoid the angel of death, and it is also where writings from Deuteronomy are placed, in mezuzahs, to signify that Jews live within and that they are obedient to the injunction of the Lord to bear his words and at all times to acknowledge them. So Emerson is putting the calling and the act of his writing in the public place reserved in both of the founding testaments of our culture for the word of God […] Emerson’s passage [also] acknowledges his writing to be posing exactly the question of its own seriousness […] he both declares his writing to be a matter of life and death, the path of his faith and redemption, and also declares that everything he writes is Whim.6

While Emerson does write ‘I hope it somewhat better than whim at last’, we should be careful not to interpret that to mean that he conceives of whimsy as a mere resting spot on the way to an idealized transcendence. Rather, his immediate deflection of his own antinomianism punctures anything resembling finality or resolution. Emerson insists here on a vital presentism that resists stasis and, crucially, frames his position as containing a critical ‘edge’. Resisting the possibility of having his thought co-opted into product—be it the product of ‘commercial activity’ or the product of liberal orthodoxy—Emerson is impelled to nail Whim Luther-like to his front door.

Amusingly, though, Emerson’s resistance demands he qualify that move almost as soon as he makes it by denigrating whim itself. Why? I think it is because Emerson recognizes that the moment a position takes on a stable sheen via proclamation—even a position predicated on Whim—the greater the risk that position runs of being stabilized as something that resembles ideology. To have that happen would ruin the playfully contrary essence of whimsy. As Richard Squibbs explains, ‘the whimsical persona rhetorically subordinates systematic explication of his philosophy, plans for social reform, and so forth to momentary inclination’.7 This should not be mistaken for nihilism, however. There is a fundamental value in the whimsical gesture. ‘Whimsicality, then, turns away instinctively from the shop logic of instrumental reason’.8 It helps readers ‘begin the process of thinking one’s way, in conjunction with others, towards the positive paradox Emerson was, in his own way, to encapsulate in the word “Whim”’.9 So, whimsy is a kind of prod that shocks us out of the stupor we never knew we were in in the first place. It provides us with productive moments of surprise and subversion, encouraging tentativeness and doubt in the face of assertions of verity. The potential outcome of such an apparently negative imperative is, at the very least, a beautifully positive invitation to treat each other gently by ‘thinking one’s way, in conjunction with others’. Again, though, this does not mean that whimsy is never employed without purpose. As my friend Sara Crangle pointed out to me in an email, Alice ‘did not like your shirt. She felt you looked bad in it. She’s a hipster who knows what looks good, so there’s some reason to believe you looked awful in your shirt. Additionally, she did not like your male posturing, and there’s a boatload of feminist history and theory that suggests she’s got reason to dislike that. So her behavior is both spontaneous and reasoned; it is an unusual and whimsical performance to throw your shirt out of reach, but there are substantial explanations for her doing so’.10

Part 3 – The Apple in History

I love whimsy so much that I dream one day of writing a book that reassesses the role whimsy plays in American twentieth and twenty-first-century avant-garde culture—from Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain right through Miranda July’s recent work in film and performance art, with stops along the way to consider, say, Charles Reznikoff’s musings as he walked from Brooklyn to Manhattan; Merce Cunningham’s choreography; Frank O’Hara’s ‘I do this, I do that’ poems; Allan Kaprow’s Happenings; Yoko Ono’s Bottoms, Jonathan Richman’s songs about ice-cream men and little dinosaurs, and beyond. For now, though, we will have to be content with an analysis of filmmaker and photographer Rudy Burckhardt’s and poet Kenneth Koch’s two minute long stop-frame animation film The Apple (1967) which Burckhardt filmed and Koch wrote the poem for that serves as its narrative.11 Koch was one of the original figures in what would come to be known as the New York School of poets (whose ranks included poets John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Barbara Guest and James Schuyler). While not particularly active in avant-garde cinema, Koch was a major figure in the New York poetry scene, hobnobbing and performing regularly with radical poets including Ed Sanders (of the proto-punk band The Fugs), Allen Ginsberg, and Black Nationalist poet Amiri Baraka. Koch proved a long-time friend of Burckhardt’s, and Burckhardt turned to Koch’s poetry repeatedly throughout his career for inspiration.12

Burckhardt’s circle from the 1950s through his death in 1999 included poet friends Schuyler, Ashbery, and O’Hara, as well as a wider group of painters, musicians, dancers, and theater people affiliated with the New York scene. Choreographers like Yoshiko Chuma and Paul Taylor and artists such as Nell Welliver and Alex Katz all made appearances in Burckhardt productions. Burckhardt also worked in collaboration with Joseph Cornell on a number of films, including The Aviary (1955), What Mozart Saw on Mulberry Street (1956), and Nymphlight (1957). Practically all of Burckhardt’s films from the 1950s on were informed by friendships with poets such as Edwin Denby, Koch, David Shapiro, Ron Padgett, Taylor Mead, Alice Notley, and Wang Ping. Their bodies and voices would play starring roles in five decades’ worth of film work.

One would think that with friends like these, Burckhardt’s films would gain wide circulation, but for the most part Burckhardt’s films were screened at loft and house parties. This was in spite of the fact that Burckhardt was part of the original New American Cinema Group, an organization of innovative independent filmmakers made up of underground luminaries including Lionel Rogosin, Ken Jacobs, and Jonas Mekas. Burckhardt’s footage of New York City was particularly well known and celebrated by major players in the underground cinema scene. Of Burckhardt’s Under the Brooklyn Bridge, for example, Jonas Mekas claimed, ‘one cannot deny its documentary value or Burckhardt’s eye for detail, his unpretentiousness. There are sequences, the children swimming under the Brooklyn Bridge is one, which belong with the best footage on New York by anybody’.13 And yet, Burckhardt seemed to practically resist attention, refusing to behave artistically in any one generic way. As if thumbing his nose at Mekas’s efforts to situate his work within the context of ‘city symphony’ films such as Walter Ruttman’s Berlin, Symphony of a City,Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera,or Paul Strand’s and Charles Sheeler’s Manahatta,Burckhardt ‘came to abandon the city symphony and the serious intentions that came with that effort. The movies directly following Under the Brooklyn Bridge were mostly story films, parodies or genre narratives made in a collaborative spirit […] He also gravitated towards collage films, sometimes lengthier than his city symphonies, but less obviously “serious,” mixing as they did comically disparate elements, intentionally shaggy and rambunctious’.14

The Apple is perhaps Burckhardt’s sweetest challenge to the kind of avant-garde seriousness we associate with Vertov, Strand et al, both in terms of its content and its distribution history. There are no records of this film being screened publically at the time of its initial production. It has proved virtually impossible to find anyone other than Anne Waldman, a poet and close friend of Burckhardt’s, who can recall the conditions and general ambiance around The Apple’s initial small-scale distribution. The poet Ron Padgett, a former student of Koch’s and friend of Burckhardt’s, remembers simply ‘I don’t recall the first time I saw The Apple […] Speaking for myself, I saw it, I loved it, it made me happy’.15 More than ten years after it was made, The Apple was finally shown to a wider public, but even then conditions were limited. In early 1979, The Apple shared the bill with two of Kenneth Koch’s plays being performed at the Brooklyn Bridge Theater Company. Other recorded instances of screenings of The Apple include a 1987 showing at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City for a retrospective of Burckhardt’s films and a 1999 event at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church, New York City to celebrate the release of a selection of Burckhardt’s films on VHS.

Despite its rather subterranean screening history, however, I focus on The Apple because the ways in which ideas of temporality, spontaneity, childishness, and parody are expressed within this tiny little film work especially well in revealing the latent and hilarious power of the whimsical affect. The Apple encapsulates ever so deliciously whimsy’s refusal of boundaries, certainties, and habits. Following Sianne Ngai’s analyses16 of ‘cuteness’ in the avant-garde, then, I want to spend the remainder of this essay analyzing The Apple in part because I’m moved by the fundamental problem that concepts like the whimsical too often ‘seem not to count as “aesthetic” at all’.17 That said, I wonder at and question the ways in which Ngai positions ‘whimsical’ as a concept that is practically analogous to ‘cute’. Looking to recuperate ‘cuteness’ as a generative aesthetic in the American avant-garde, Ngai turns her critical eye to a number of purportedly ‘cute’ poetic texts, from Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons to ‘Lorine Niedecker’s granite pail, Robert Creeley’s rocks, John Ashbery’s cocoa tins’18 to a sustained study of Bob Perelman’s and Francie Shaw’s Playing Bodies. Ngai attaches the singular banner ‘cute’ to a number of disparate texts. For example, Gertrude Stein’s radically annoying if often charming prose studies in Tender Buttons are framed by Ngai as ‘lyric poetry’19 whose power lies in their purportedly indecent, feminized cuteness. True, Ngai acknowledges that ‘For Stein […] cuteness is anything but precious or safe’.20 The problem here is not that Ngai is insensitive to Stein’s disruptive, digressive poetics. Rather, the issue is Ngai’s relatively loose use of the word ‘cute,’ as her argument agitates instead for us to replace Ngai’s ‘cute’ with our ‘whimsical’. The etymology and significations of ‘whimsy’ certainly are amenable, as we’ve seen, to the cuddly and adorable aspects of ‘cute’ that Ngai so brilliantly identifies throughout her argument. Crucially, though, ‘whimsy’ invokes modes and affects affiliated with cuteness primarily as a seduction technique – we’re drawn in, only to then be kicked, contradicted, or encouraged to lose our focus via textual strategies including (in Stein’s and related artists’ cases) digression, punning, and opaqueness.21

In other words, cuteness ain’t whimsy. Cuteness lends itself to being clucked over and consumed. As I will illustrate through the example of The Apple,whimsy—while allowing for cuteness—wards off consumption. The Apple, in its complex and simultaneous incorporation and deflection of dominant visual and verbal discourses circulating around the late 1960s avant-gardes, strikes me as precisely the kind of work that invites sustained analysis despite the fact that it barely made a dent in the counterculture of its own time.

Part 4: Getting Into The Apple

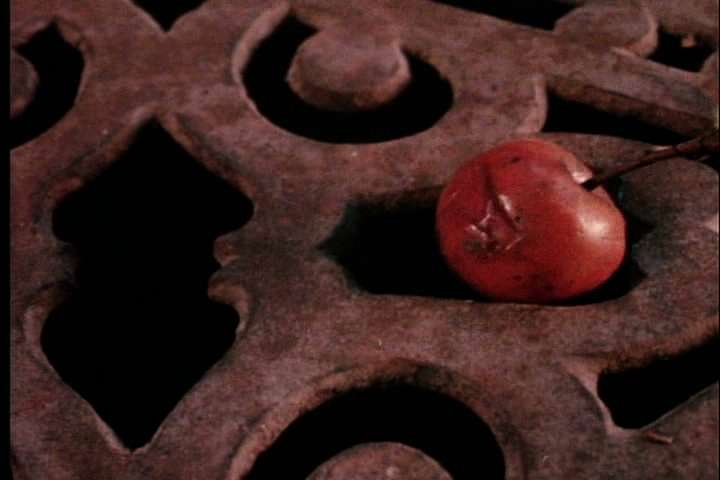

The Apple opens in the bedroom of a rustic, light-filled country home. Through the medium of stop frame animation, an apple is pictured moving along the bedroom floor. The next two scenes are composed of two close-ups of the apple—one as if from the front, one as if from the back. The apple then moves along the floor of another room in the cottage, initially rolling towards a fireplace, then (seemingly having a change of heart) towards a wooden chair by a window. The apple then continues its little journey, pausing by a pair of child’s sneakers, toy cars, a toy drum, and a ball. It then moves on to another room, narrowly escaping being crushed by a rocking chair and almost hitting a table leg in the kitchen. After the table-leg incident, the apple rolls past an open door by which we see the sneakers move incrementally. Framed by the open door is a lovely unkempt lawn and apple tree. It is a nice sunny day—spring or summer, maybe. At this stage, the spell induced by stop-frame animation is broken as a little boy in a bright red shirt and blue shorts is filmed running across the lawn. The next shot finds the apple rolling across the floor of another room. We then find the apple literally being thrown and pulled along by a string in real time down some wooden stairs into yet another room. Suddenly, the apple is filmed in close-up rolling back and forth over a patterned iron grate. The apple somehow shrinks drastically in size and falls through a bell-shaped opening in the grate. The next scene is shot from underneath the grate, focusing on light streaming through a window in the background. The camera then pans desultorily around the cellar that the apple fell into, lingering melancholically on chinks of light visible through cracks in wooden walls and rock-filled crevices. We are then treated to the sight of the apple’s heroic reappearance as it pops out of a gap on the outside of the house and begins to fall down a large snow-bank in slow-motion. The penultimate scene finds the apple rolling down a dirt road dusted with snow into the horizon of what promises to be ever more adventures. The final scene focuses on a snow-covered field as the final credits roll—poem by KENNETH KOCH, music by TONY ACKERMAN [and] BRAD BURG, sung by KIM BRODEY, filmed by RUDY BURCKHARDT. Colors throughout are predominantly babyish and goofy—school-bus yellow, fire-engine red, and the like.

Brodey, accompanied by a piano and guitar duo, sings Koch’s poem with a little school-girl’s mien:

Here’s the apple as it rolls along the floor,

It seems to sing a song what’s more

It’s in danger…the apple is in trouble, just a bubble of doubt

Must cross its mind. Are apples blind?

In any case…

As it proceeds to roll along over the floor

– look! It may hit the chair legs but, no more

We need not fear that, it evades them and goes on

To hit the table? No! Goes on

across the slightly not level floor

But here alas! Apple green and white and red

your head you may injure oh beware watch out…

Yes? No? Oh yes!

The apple has fallen in the grate…goodbye.

But no it continues to go along

And now we have seen it has fallen outside

Aren’t you cold apple, in the snow?

And it continues…

How red and green and white to go rolling along…

The text is classic Koch, exemplifying the faux-naiveté of much of his work. (The description of the apple’s fall into the grate, for example, works as a hilarious and tender take on anxious breathlessness, horror, and resigned mournfulness).

Such naiveté is extended in the visual language Burckhardt uses in The Apple, which actually is rather unlike most of Burckhardt’s other films. Burckhardt rarely used stop-motion animation outside of The Apple. The Apple does not reflect the beautifully shot documentary function of his early city symphonies. It does not generate the ‘wispy, fragile quality poised between documentary and reverie’22 characterizing Burckhardt’s works with Cornell. It does not use montage to hypnotic, melancholic effect as seen in his later poetry films like Ostensibly (built around the recitation of John Ashbery’s poem ‘Ostensibly’), nor does it serve to spoof genre as Lurk (Burckhardt’s version of the Frankenstein story) and Tarzam (Burckhardt’s Tarzan satire, starring the irrepressible Taylor Mead as Tarzan) did. Additionally, while some of Burckhardt’s films were short, they were never two minutes short.

Given that The Apple is unique within Burckhardt’s oeuvre, it is clear that Kenneth Koch’s role in the film played a large part in determining the film’s distinctiveness. A committed reader of Koch’s work, Burckhardt found a model for the overall register of The Apple in Koch’s poetics. Consider, for example, Koch’s early and radically disjunctive When the Sun Tries to Go On (1953) which begins with the practically inscrutable lines ‘And with a shout, collecting coat hangers / Dour rebus, conch, hip, / Ham, the autumn day, oh how genuine! Literary frog, catch-all boxer, O / Real! The magistrate says “group,” bower, undies / Disk, poop, Timon of Athens’23; the mock-epic Ko; or, A Season on Earth (1960) (written in strict Byronic ottava rima stanzas and centered on the exploits of a Japanese baseball player); the synthesis of verse drama conventions with a markedly surrealist sensibility in Bertha and Other Plays (1966) (‘My grandfather at eighty offered / The stanza a million dollars / That could make him feel as though / He were really a lagoon’24). Reviewing Bertha, a book published just one year before The Apple was finished, Denis Donoghue affirmed ‘Koch implies in his smiling way that nothing is too silly to be said or sung, provided we know exactly how silly it is’.25 As elaborate as Koch’s poetry is with its bravura employment of complicated forms and genres, Koch’s silliness, evident in his love for turns of phrases like ‘Disk, poop, Timon of Athens’ alongside his development of whimsical and glee-driven characters throughout his works, appears to have informed Burckhardt’s visual imagination significantly.

Koch’s playfulness certainly resonates with Burckhardt’s decision to make The Apple appear slight, as if it was nothing more than a good-humored home-movie despite the fact that the film was shot over the period of at least a year (as we can see given the change of seasons in The Apple, which begins in spring or summer and ends in winter), involved cross-disciplinary collaboration, and employed the laborious process of stop-frame animation throughout. Casual viewing, after all, might leave the audience thinking wrongly that The Apple is a self-consciously crude and child-like work. Indeed, Burckhardt himself is so intent on ensuring The Apple feels minor that he refuses the viewer’s uninterrupted identification with the developing narrative a number of times by interrupting the visual flow with wholly unexpected displays. As stated above, for example, Burckhardt films the apple rolling down some wooden stairs in real time at the point when Brodey warns ‘It goes on across the slightly not level floor’. It is as if Burckhardt couldn’t be bothered anymore to move the apple incrementally between individually photographed frames, choosing instead to simply toss the apple cavalierly despite the fact that viewers were lulled at this stage into thinking the apple was going to move as sweetly and consistently as, say, the Orange did when she sang Carmen on Sesame Street.26 However, one can read more deeply into Burckhardt’s apple toss, recognizing this whimsical gesture as a moment that calls into question the lingering aura of professionalism informing our experience of the film. That is to say, even in the context of a simplistic narrative taking place in a two-minute long film, we can’t help but be delighted by the filmmaker’s rough skill as it is manifested in the special effects of stop-frame animation. We giggle and marvel at the ways in which the apple in The Apple appears practically anthropomorphic. When that apple suddenly and simply rolls across the floor, however, our delight is compromised by our recognition that we are basically just watching a wooden apple being manipulated through space and time. Our willed suspension of disbelief collides with a new skepticism—are we merely watching a dumb, poorly made home-movie?

Having watched this film countless times in company, that apple toss is one of the few instances in which people in the screening room awaken from their passivity and begin addressing each other. ‘Did you see that?’ they say, and ‘What the hell?!’ Compelled to think our own way in conjunction with others, we recognize the real time apple toss as a kind of situation in which we are deflected away from our slavish adherence to the film’s stable narrative and cutesiness towards a far more contingent, even mildly insurrectionary space in which nothing—not the trajectory of the film, not our willing resignation of ourselves as isolated passive consumers—is as clear and comfortable as we initially thought it was.

While the willfully amateurish apple toss is one example of Burckhardt’s delaying or repudiating a straightforward narrative structure in favor of disruptive self-reflexivity, the scene when the apple is filmed in slow-motion plunging down a snow-bank speaks to a wider context the film knowingly if casually plays within. At this point in the film’s narrative, the apple has been framed as a wandering hero encountering and persevering against formidable obstacles (the table, the rocking chair) only to dramatically and drastically fall into the grate and disappear, apparently forever as per the accompanying lines in the poem, ‘the apple has fallen in the grate…goodbye’. Yet that apple persists, reappearing from out the front of the house (‘But now it continues to go along / And now we get to see it’s fallen outside’). Particularly in light of the fact that viewers were under the assumption that the apple had just fallen forever into a grate, I always think about the pathos inherent in slow motion as we find it exploited in works by directors like Akiri Kurosawa. Consider, for example, the series of slow-motion deaths in The Seven Samurai (1954), in which a couple of bad guys are killed by sword-wielding samurai and practically twirl in slow motion before they hit the ground. In The Apple, however, pathos is turned into bathos. It is not a hero or villain who has seemingly died only to miraculously reappear, after all. It’s just a little toy apple. As we find in so many of Koch’s poems and as I will now elaborate, whimsy aims its sights at high seriousness and the sober response such seriousness always demands from its audience.

The Apple as Byronic Mock-Epic

The Apple offered Koch a chance to collaborate on a kind of visual analogue to his decades-long fascination with the mock-epic form—a fundamentally whimsical usurpation of ‘serious’ ‘high-art’ literary discourses. The Apple can be understood as the beginning of a mock-epic, a Canto 1 if you will of a tacitly larger work. As in all epics and mock-epics, The Apple centers on a hero—the apple itself, a kind of crunchy stand-in for Odysseus, Jason, Achilles, Aeneas, and so forth. The narrative of The Apple, as in Homer’s Iliad, Pound’s Cantos, and Koch’s When The Sun Tries To Go On, begins in medias res with the lines ‘Here’s the apple as it rolls along the floor / It seems to sing a song what’s more / It’s in danger’. Typical of the epic convention, the apple appears to be on its way to another place. As the quest narrative is so often a constituent part of the epic convention (Jason looking for the golden fleece, Odysseus’s quest to get home), the apple is on a mission (albeit an unknown one) that is fraught with its own dangers.

I want to pay special attention to the opening lines of the film: ‘Here’s the apple as it rolls along the floor / It seems to sing a song what’s more.’ This is an invitation for us to consider the apple alongside other epics in which the Muse or the hero himself is invoked at the beginning of the narrative to sing—for example, Milton in Paradise Lost requesting the ‘heavenly muse’ to sing ‘Of Mans First Disobedience’27; Homer insisting ‘sing it now, goddess, sing through me / the deadly rage that caused the Achaeans such grief’28 in The Iliad. Of course, it’s just an apple in The Apple, not Satan, not Odysseus, not the muse or goddess. Why are Koch and Burckhardt pointing to epic convention, only to make it absurd by realigning it to encompass the arguable ‘adventures’ of a toy apple? What, if anything, is the point of such genre trouble?

In short, the mock-epic offers Koch and Burckhardt a way of poking fun at order. Byron in particular is a useful model to read alongside The Apple, particularly given Koch’s use of the same ottava rima stanzas and rhyme schemes (three alternate rhymes and one double rhyme) in poems including Ko, The Duplications, and Seasons on Earth that we find in Byron’s Don Juan. Given the ham-fisted rhymes employed throughout The Apple, I want to place The Apple in dialogue with Byron’s rhymes in Don Juan, as the use of rhyme in the representative works offers us a lesson on how rhyme can be used to engage with and parody the authority of both the traditional epic and the military itself.

Byron, as Jim Cocola explains, recognizes—and even emphasizes—the politics of the rhyming function, in part by strategically choosing not to rhyme well or not to rhyme at all when it came to his ‘enumerations of military heroes. […] Byron acknowledged the legions of omitted French patriots in Don Juan with awkward monikers to be “Exceedingly remarkable at times, / But not at all adapted to my rhymes”. Likewise, the conjured Russian patriots whose names proved “discords of narration”, which could never be “tune[d]…into rhyme” were therefore left unmentioned’.29 Helpfully in terms of our reading of The Apple, Byron did not avoid making difficult rhymes because he couldn’t be bothered to try, but rather because he was working towards repositioning a vaguely confrontational, silly affect—whimsy, really—into something that could be used subversively. As Philip Hobsbaum understood it, Byron was the greatest and last ‘exponent of the subversive mode in verse’, whose poetic practice equals a ‘debunking process’ accomplished through ‘an extent of wild rhyming’.30

The Apple, I think, uses rhyme for similar ends, if less obviously. That is, it rhymes awkwardly and surprisingly and hilariously to guarantee the apple signifies useless artifice, undirected creativity, and general tenderness in tacit contrast to the uses of rhyme in the traditional epic, in which rhymes are employed specifically to praise arms and men. Like epic heroes of yore, the apple must face a series of seemingly insurmountable dilemmas—but here there are no horrifyingly violent battles, no sirens singing sailors towards the jagged rocks, no six-headed beast, no whirlpool. Rather, we have the more mundane if equally lethal rocking chair, table leg, and grate chasm to be wary of. These unformidable obstacles are described in part through end, internal, and slant rhymes so elemental (floor / more; red / head; trouble / bubble; mind / blind) as to seem almost frivolous.

Also deviating from the trajectory of the traditional epic, the apple’s scurrying around is open-ended. We don’t know what’s motivating it. If we can assign any one character trait to the apple, what stands out is not its willingness to confront danger and seek victory over its adversaries, but rather its efforts to avoid conflict. In light of the apple’s consistent efforts to skirt anything resembling a fight, we can now consider how The Apple might have reflected and critiqued attitudes about genre, politics, and the avant-garde itself that can inform contemporary readings of the film.

The Apple, as we have established,played knowingly with the anti-militaristic aspects of the mock-epic. It was also produced in the context of an increasingly politicized avant-garde culture responding ever more vociferously to American foreign and domestic policy. What, then, were the epic battles being fought in real time, in real space, in 1967 around the time Burckhardt’s and Koch’s film was made? In January of 1967, for example, American and South Vietnamese troops unleashed Operation Cedar Falls to counter Vietcong successes. Cedar Falls was to become particularly notorious when Americans ‘laid waste to the whole region [of the Iron Triangle], including the village of Ben Suc, which gained notoriety in the American press after being completely leveled’.31 Offensives such as these were being carried out early in 1967 even as Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara would admit later in the year to a Senate subcommittee that US bombing raids were ‘ineffective’.32

On April 4, 1967, Martin Luther King linked the Civil Rights Movement to the anti-war movement, insisting that the United States government was ‘the greatest purveyor of violence in the world’33 and encouraging military-age young men to resist the draft. Reflecting King’s rage—and despite the fact that the summer of 1967 was widely referred to as the ‘Summer of Love’ given the hippie phenomenon in San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury and other countercultural hotspots—American college students were becoming increasingly militant in their opposition to the war. ‘Student protests were escalating, not just in Washington, D.C., but on nearly every campus in the country. At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, three hundred protestors picketed outside the Commerce Building on October 18 [1967], protesting the presence of recruiters from Dow Chemical Company, manufacturers of napalm and chemical defoliants used by U.S. forces in Vietnam […] During the Madison protest, local police used tear gas to break up the picketers, who fought back; in the confrontation fifty students and twenty policemen were injured’.34

I invoke the Summer of Love, the Vietnam War, and the Civil Rights movement primarily because the film’s overall tone and content is in some ways sympathetic to that aspect of the counterculture that created faux-naive works to challenge, however gently, the war machine. In light of The Apple’s pastoral vibe, consider the film alongside Allen Ginsberg’s term ‘flower power’ which the poet coined sometime around 1965, or Andy Warhol’s Flower wallpaper covering poet Ed Sanders’ bookstore The Peace Eye in the mid 1960s. Imagine the film as it might have played alongside the street-oriented Bread & Puppet Theater handing out flowers and balloons to its audiences; Bernie Boston’s iconic image ‘Flower Power’ showing a young man placing flowers in the gun barrels of soldiers at an anti-war demonstration on October 22, 1967; the now famous 1967 ‘Another Mother For Peace’ organization’s logo—a sunflower with the words ‘War is not healthy for children and other living things’ that ended up on bumper-stickers, key-rings, and posters across the United States.

This little film would have been understood—given Burckhardt’s and Koch’s personal connections to figures like Ginsberg and Warhol and to their general sympathy for the counterculture in New York during the 1960s—as chiming compellingly with the ‘flower power’ counterculture that, by 1967, had become so dominant in the American visual-political imagination. As Burckhardt himself understood his relationship to the counterculture of the time, ‘the hippie, underground, pro-sex, anti-Hollywood revolution in the early Sixties [arrived during] my late forties. I became a fellow-traveler and beneficiary […] I had a good review by Jonas Mekas who was fighting censorship and promoting far-out, uninhibited films’.35 During the same year The Apple was produced, Burckhardt was teaching film at the University of Pennsylvania, screening ‘such avant-garde stalwarts as Un Chien Andalou, Anemic Cinema, O Dem Watermelons, and Window Water Baby Moving, as well as the films of René Clair, a particular favorite of Rudy’s.’36 Koch himself, while not an anti-war radical by any means, was nonetheless becoming increasingly involved in the major questions of the day. 1967 found him supporting the peace movement vocally by taking part in readings against the war, and beginning work on his important book The Pleasures of Peace and Other Poems (1969). His affiliation with radical poets including Allen Ginsberg and Ed Sanders left no doubt as to what side he was on. Koch ended up supporting student activists at Columbia University during their iconic occupation of University buildings in April 1968. Indeed, Anne Waldman, poet and former director of the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church—perhaps the preeminent showcase for alternative poetics in the 1960s and 1970s—recalls seeing The Apple around the time it was produced, and notes that both Koch and Burckhardt ‘moved in myriad artistic circles (the Living Theatre, Diane di Prima’s Poets Theatre) and within the art realms that weren’t necessarily viewed as “political” as content. As someone who was primarily identified with Second Generation New York School/New American Poetry and curating at the Poetry Project where Rudy and Kenneth were participants, and also increasingly caught up in anti-war activity, my sense of the aesthetics of “The Apple” was consistent and refreshing and could be included in the broad swathe/ cultural maelstrom of those days’.37

Waldman’s inclusion of The Apple within a countercultural context can help us extend our reading of how the film’s very length might represent a kind of political and aesthetic critique. The Apple, through parodic uses of slow motion, stop motion, and rather jarring cuts from sunny days to winter snowscapes, practically telescopes epic time into filmic time.38 We don’t need to read hundreds of pages, the film asserts gleefully, to get a sense of epic scale. Waldman’s recollection of the viewing and context around The Apple again proves helpful here, as she emphasizes the ways in which Koch revisioned smallness: ‘I was already a reader of Kenneth Koch’s poetry, and had met him, seen him read thus knew his wit, playfulness, his way of making something small quite large, even epic. He always reached for the macrocosm. I remember when we toured a bit together in Europe he wanted a brass band to meet us at the train station! Thinking of his brief plays in this context (micro to macro)—often running just several minutes—that required huge sets and fanfare and scurrying about on stage’.39 We can then understand that Koch and Burckhardt are perhaps creating a willfully minor art to launch a counter-attack against the way aesthetic value is so often predicated on the grand gesture (from Homer’s epics to, say, Pollock’s canvases), and to resonate amusingly with other pastorally-tinged whimsical images and texts produced by the counterculture to resist militarism.

The Apple in and against the Avant-Garde

I have argued that whimsy in The Apple stems in part from the mock-epic tradition, and suggested how whimsy might have been employed to agitate against the high-art status accorded to the epic. I have also discussed how whimsy might be used by Koch and Burckhardt to interrogate State power, however elusively. To move on, then, I want to analyze how whimsy in The Apple is aimed squarely at the sixties avant-gardes even as it simultaneously can be located as of a piece with the counterculture. What role does The Apple play in contesting the ground staked out by the dominant American and European avant-gardes in the late 1960s, even if figures affiliated with those very avant-gardes may never have actually seen The Apple?

In light of The Apple’s seemingly naïve story-line, we must remind ourselves how by 1967, narrative itself—let alone the whimsical tale propelling The Apple—was held to be politically suspect. Filmmaker Stan Brakhage (whom Burckhardt knew and whose films Burckhardt screened for his students), conceived of his serial work in part as based on an effort to rid his art of narrative or what Brakhage more prosaically called ‘story’. As Brakhage wrote in a letter to poet Ronald Johnson, ‘I once said that story, like melody, was unavoidable in a continuity art; but my making since then has been especially devoted to the obliteration, or at least avoidance, of story. I suppose that in this sense I’m an artist a bit like Anton Webern who composed music which seems (at his best) to turn on itself, like a mobile, and resist ALL sense of “continuity”’.40 Rejecting narrative was not merely a refusal of closure, but a wholly political intervention opposed to what Brakhage understood to be the violence implicit in and disseminated by ‘narrative drama’: ‘Narrative drama, as a form that’s unchanged since the Greek, is a trap that’s loaded people with the dice that makes it very possible that the Third World War will be in Jerusalem and all the apocalyptic visions of drama will be fulfilled. People will move to try to fulfill those prophecies if we don’t move to get out of the three-act play’.41 1967 was also the year that gave us that seminal document of post-New American cinema—Michael Snow’s Wavelength, a 45 minute-long zoom shot focused on a photograph of waves at one end of a New York loft apartment.42 Given ‘the film’s durational strategy, we feel every minute of the time it takes to traverse the space of the loft to get to the infinite space of the photograph of waves—and the fade to white—at the film’s end. The film inspires as much boredom and frustration as intrigue and epiphany’.43 True, Wavelength was not without its humor, its tentative narratives, and a soundtrack of its own. Nevertheless, Wavelength marked an important shift away from the often vatic, rhapsodic documents of the New American Cinema to the arguably more formally austere films we associate (if loosely and often problematically) with the so-called Structural film movement. In light of this turn, The Apple seems even more of an oddball piece, with its song, its clear (if open-ended) story, and so on.44

In Europe, the avant-garde was exhibiting a similar suspicion, if not downright contempt, for art that dared to suggest simple, apparently non-ideological pleasure was a valid primary response to the consumption of art. Jean-Luc Godard—whose Breathless and other early works were appreciated by Koch, Ashbery, and other Francophile New York School writers—stopped making films in 1967 for general theater audiences to begin work with the Dziga Vertov group, a radical collective of filmmakers dedicated to producing agitprop films designed to foment revolutionary change. Godard refused to release Vertov Group-affiliated work commercially, ‘and outside of an occasional screening at the [Paris] Cinematheque, the only opportunities to see these films have been screenings set up for groups of militant workers or militant students’ organizations’.45 Echoing Godard’s repudiation of l’art pour l’art, writers for POSITIF magazine made it clear they had enough of many of the films of the French New Wave, particularly those that did not critically address their particular historical moment. As Philip Watts explains, ‘The young directors who emerged in the early 1960s, the story goes, were more interested in intimate tales of a new generation, in the history of cinema, and in what Robert Benayoun at Positif had called “a flight into formalism” than they were in making films about historical events or France’s colonial wars’.46

The London film scene was similarly motivated by a sense of political urgency influenced in part by the communitarian ethos of its counterpart in New York, as it was increasingly invested in the rigors of film theory anathema to Koch’s and Burckhardt’s sensibilities. Peter Gidal, for example, long associated with the London Filmmaker’s Co-Op, described his films of the period in the most austere of terms. Gidal wrote about his film Clouds, ‘The anti-illusionistic project engaged by Clouds is that of dialectic materialism. There is virtually nothing ON screen, in the sense of IN screen. Obsessive repetition as materialist practice, not psychoanalytic indulgence’.47 There is simply no place in Gidal’s, Godard’s and related politicized filmmakers’ works for The Apple, a film predicated quite literally on a toy and its apparently meaningless meanderings. Gidal’s and Godard’s political aesthetic is a hard man’s aesthetic, one in which the borders between the movie camera, revolutionary ideology, and the Kalashnikov were becoming more and more blurry. Their avant-garde, to apply Sianne Ngai’s argument to this particular context, ‘is […] imagined as sharp and pointy, as hard or cutting-edge.’ Objects like our apple ‘have no edge to speak of, usually being soft, round, and deeply associated with the infantile or the feminine’.48

Implicitly contesting the adversarial styles of the dominant avant-gardes, The Apple very much foregrounds the ‘infantile or the feminine’ as qualities. The story itself, as stated earlier, is sung by Kim Brodey with a school-girl’s mien, while the only human visual presence in this film is that of the little boy glimpsed running outside the door of the cottage just after we see the apple evading the rocking chair and table leg. This surprising glimpse of childhood (surprising because it is in real time, is an actual human being and not a prop, and contrasts with the animation dominating the rest of the film) is, I would suggest, in concert with my overall argument that seeks to position The Apple as a whimsically dissident film that, in an Emersonian spirit, is confronting all orthodoxies, be they avant-garde aesthetics or established political ideologies. Far from attempting to achieve purportedly objective revolutionary goals like Gidal or Godard, The Apple’s emphasis on running and playing, on toys and silliness, emphasizes how the film repudiates any and all positions predicated on reason and absolutist ideology.

Thus, The Apple is not so much serving as a self-criticism of art in bourgeois society, as Peter Bürger understood the historical avant-garde’s function, but nor is it falling prey to Bürger’s pessimistic view ‘that post-avant-garde art has only the ability to dispose of all traditional stylistic and aesthetic forms’.49 While The Apple is a fun and easy film, it is also cognizant of its avant-garde credentials and its place within art-historical practice. Koch’s and Burckhardt’s use of childhood tropes and the anthropomorphic apple itself resonates with the use of puppets as a motif in Dada performance, and especially with Hans Richter’s unsettling and funny use of stop-motion animation to create visions of flying bowler hats in his film Ghosts Before Breakfast.50 The Apple’s elision of a clear ideological position resonates both with Dada’s refusal of itself (‘Dada is anti-Dada’ went the great proclamation) and Emerson’s own performative proto-Dada self-negation when he followed up his nailing Whim to the lintels with ‘I hope it is somewhat better than whim at last, but we cannot spend the day in explanation’.51 Thinking about the film in terms of its own cultural-historical moment, The Apple’s location in the home can certainly be read, for example, as extending the ‘home movie’ aesthetic and DIY values more generally speaking as we find it in film-works by Maya Deren and Stan Brakhage. Pointing slyly to museum-ready art in part to avoid the problematic defined by Adorno’s critique of ‘the childish’ (‘If it remains on the level of the childish and is taken for such, it merges with the calculated fun of the culture industry’52), the film has a vaguely Pop sheen as well. The apple itself evokes Claes Oldenburg’s sumptuous pies, ice-cream cones, and burgers. Jasper Johns’s Light Bulb sculpture would fit nicely in a corner of the house. Is that an Alex Katz painting I see on the wall of the summer house?

However, these resonances do not mean The Apple is nostalgic or merely derivative. The film’s blithe recourse to tropes of childhood are expressed through resolutely non-Dada-like ‘traditional stylistic and aesthetic forms’ (rhymes, the mock-epic, narrative, and so forth), reconciling what are generally understood to be mutually exclusive positions. The Apple’s juxtaposition of styles serves to unsettle those of us who continue to believe in either the eternal verities and relevance of established forms and genres or the progressive possibilities of a radical, experimental poetics.

These qualities are precisely what make The Apple such a prescient film. It’s a film that—located as it is in 1967, and produced by two artists who were by that time decades into a deep investment in the poetic and filmic avant-gardes—is in part singing the swan song of the counterculture in a number of ways despite its visual valences with flower power. The Apple undercuts the narratives of surety adopted by the leftist avant-gardes. Nothing in this film is certain, other than the endless possibilities of diffuse play (the final line in the film-poem is, after all, ‘And it continues…’). The film looks ahead to the faux-naïve work of Murakami, of Koons, of that part of post-Pop, post-Minimalist, post-modernist visual culture that finally, with a shrug and a smile and a song, acknowledges the battle between subculture and Capital was always and forever tenuous, elastic, compromised. And yet, The Apple (crucially) refuses Murakami’s, Koons’s, and related artists’ aestheticized participation in free-market mechanisms.

While ‘the ultimate index of an object’s cuteness’ as Ngai sees it, ‘may be its edibility’53, the apple as we see it in the film invokes consumption in its most literal sense only to refuse it. To bite into Burckhardt’s wooden apple would more likely result in a chipped tooth than it would an ‘oh yummy!’ Contradicting its own ‘nature’ as crunchy, fiber-rich treat, the apple is in the end as elusive and seductive as that little boy who we barely glimpse as he runs past the open door. Binaries in this film—between summer and winter, stop-motion animation and live action, even between materiality and immateriality (as we see during the practically Ovidian metamorphosis when the apple suddenly becomes small enough to fall through the grate)—are temporarily extinguished. For two glorious minutes, we are treated to a goofily prelapsarian vision in which the world is one wholly predicated on play, the usurpation of the big (the epic genre, the ‘serious’ avant-garde) by the small (the apple, the little boy, the toys).

The Apple is clearly not committed to identifying and overthrowing an established literary/political order. Not for Koch and Burckhardt the histrionics of an Amiri Baraka or Allen Ginsberg railing against the military industrial complex or racism. (In fact, Waldman remembers thinking of the film as ‘a sly intervention on [Burckhardt’s and Koch’s] part in fact…an antidote to stridency’54). Rather, the remit of The Apple is to develop and sustain a position of what critic Mark Silverberg identifies as an active, whimsical indifference to oppositional binaries, a position that, in the words of poet John Ashbery, hovers productively ‘between the extremes of Levittown and Haight-Ashbury’.55 Does this mean The Apple is disengaged if adorable fluff, lacking entirely in the kinds of dissident impulses we’re trained to look for in our avant-gardes? Well, yes and no. I’d like to apply to The Apple Silverberg’s argument about the New York School poets’ opening up ‘a space beyond ‘‘radical art’’—and its favourite gestures of antagonism, individualism, and futurism—for a different avant-garde which follows a presentist, processual, and apparitional (rather than oppositional) aesthetic’.56 The Apple is certainly not a sterling work of individual, auteur-driven genius. Rather, it is a piece in a puzzle of a wider culture committed to producing, to quote Silverberg again, ‘an art in motion rather than a static, stable […] art’. (2010, 13).57 The Apple, particularly given its place as a lighthearted collaborative artwork that re-inscribes the formerly no-no genres and styles of narrative, epic, song, and nursery rhyme into a still ‘underground’ context, helps us as viewers interrogate the high seriousness ascribed both to the figure of the lone artist forever faithful to his or her single genre as well as to the increasingly politicized sixties avant-garde. We see it, we love it, it makes us happy.

Coda

I thought it would be funny if I got a t-shirt made for Alice’s twenty-fourth birthday that read ‘I LUV WHIMSY’ so she could wear it when she went to parties or whatever. After finding a suitably ugly purple t-shirt in a second hand store, I went to one of those silk-screen places on lower Broadway that could print the letters on the t-shirt for me. I wrote down ‘I LUV WHIMSY’ on a card and gave it to the guy behind the counter, telling him ‘That’s what I want on the t-shirt, in big black letters’. The guy told me to come back in an hour. When I returned, he gave me my t-shirt back, but I was dismayed to find that my ‘I LUV WHIMSY’ had been printed as ‘I LOVE WHIMSY’. ‘Why didn’t you follow my instructions?’ I asked the counterman. ‘Well, our printer saw you misspelled ‘LUV’, so he thought he was doing you a favor by spelling it correctly!’ ‘I’m not an idiot’, I retorted. ‘Of course I know how to spell ‘LOVE’.

After our final break-up, Alice gave me the I LOVE WHIMSY t-shirt back, admitting she never really would wear it, not under any circumstances. Since then, I wore the t-shirt outdoors only occasionally, mostly when I went jogging. About six years ago, I cut off the sleeves, only to realize I looked too ridiculous in it to ever dare being seen wearing it in public. The last time I wore it was about three years ago when I vacuumed my apartment on a hot summer day. I didn’t want to get any of my nice t-shirts sweaty.

Notes

Daniel Kane is Reader in English and American Literature at the University of Sussex. His publications include All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s(2003) and We Saw the Light: Conversations between the New American Cinema and Poetry (2009)

Alice Robinson, E-mail to the author. August 12, 2013.

“Whimsy | Whimsey, N. and Adj.” 2014. OED Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed May 5, 2014. http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/228374.

Ben Jonson, The Selected Plays of Ben Jonson: Volume 1: Sejanus, Volpone, Epicoene Or the Silent Woman (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989), 207.

Thomas Jefferson, Memoir, Correspondence, and Miscellanies from the Papers of T. Jefferson (F. Carr & Co. 1829), 508.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self-Reliance (Maryland: Arc Manor LLC, 2007), 19.

Stanley Cavell, Cavell on Film (New York: SUNY Press, 2005), 100.

Richard J. Squibbs, ‘Civic Humorism and the Eighteenth-Century Periodical Essay.’ ELH 75.2 (2008), 392.

Ibid., 394.

Ibid., 403.

Sara Crangle, E-mail message to author, 17 August 2012.

Rudy Burkchardt and Kenneth Koch, The Apple: Rudy Burckhardt Films. San Francisco, CA: Microcinema International, 2012. DVD.

Indeed, one of Burckhardt’s last films On Aesthetics (1999) was based on Koch’s series of poetry aphorisms ‘On Aesthetics’ in Koch’s book One Train (1994).

Jonas Mekas, Program Notes for Rudy Burkchardt’s Under the Brooklyn Bridge. Rudy Burckhardt Films. San Francisco, CA: Microcinema International, 2012. n.p.

Phillip Lopate and Vincent Katz, Rudy Burckhardt (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2004), 29.

Ron Padgett, E-mail to the author. September 9, 2012.

Ngai’s article, which first appeared in Critical Inquiry (2005), has since been expanded and included in her 2012 book Our Aesthetic Categories: zany, cute, interesting. I quote from both sources.

Sianne Ngai, ‘The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde.’ Critical Inquiry 31.4 (2005), 813.

Ibid., 815.

Ibid.

Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 70.

Ngai seems a little hesitant to make the kinds of distinctions between words like ‘cute’ and ‘whimsy’ that I’m insisting here must be made. For example, her reading of Russell Edson’s poem ‘The Toy-Maker’ – a text I would argue is radically whimsical – is defined as inherently cute because ‘The poem […] toys with how our very ideas about poetry fluctuate between the grandiose and the abject, or between poieisis and poo’ (2012, 71). And yet, Edson’s text initially seduces the reader with fairy-tale style storytelling (‘A toy-maker made a toy wife and a toy child. He made a toy house and some toy years. / He made a getting-old toy, and he made a dying toy. / The toy-maker made a toy heaven and a toy god’) only to then end with the proverbial kicker ‘But, best of all, he liked making toy shit’ (qtd in Ngai, 2012,71). Ngai’s insistence in framing and, indeed, paraphrasing the poem’s meaning within the context of ‘cute’ elides, I would argue, the poem’s inherent nastiness – a nastiness whimsy has always made room for and is often determined to effect.

Lopate and Katz, Rudy Burckhardt, 31.

As Joshua Wiener puts it, ‘“When the Sun Tries to Go On” opens mid-sentence, like [Ezra] Pound’s Cantos; only the sea on which Koch embarks is of a different heroic motion, the epic of everyday objects swirling amongst literary scrap wood and milkyways of diction, swaths of glowing particles syntactically adrift’. Joshua Wiener, ‘The Collected Poems of Kenneth Koch.’ Chicago Review 52.4. (2006): 346.

Koch’s disjunctiveness is practically a retort to Pound’s formally similar but ideologically distinct efforts in his Cantos to transform a poem into a master narrative applicable across cultures and time. Where Pound insists on prescriptions – the reading lists and tallies of historical great men that Pound foreground throughout his epic work – Koch prefers providing readers with examples of how releasing ourselves from the rules of grammar and syntax and, analogically speaking, any and all rules predicated on a stable, rational order, can lead to radical joy. Koch’s is a kind of jovial, productive and eminently whimsical anarchism that dances towards, around and away from the imperatives we find in Pound’s work.

Quoted in Denis Donoghue, ‘Miracle Plays.’ The New York Review of Books 20 Oct. 1966. The New York Review of Books. Web. 30 Apr. 2013.

Ibid.

See http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jG-0_p_yefg to view this particular skit from Sesame Street.

John Milton, Paradise Lost (New York: G. Routledge and Sons, 1905), 3.

Homer, The Iliad, trans. Stephen Mitchell (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012), 1.

Jim Cocola, ‘Renunciations of Rhyme in Byron’s Don Juan.’ SEL Studies in English Literature 1500-1900 49.4 (2009), 844.

Ibid., 845.

James S. Olson and Randy W. Roberts, Where the Domino Fell: America and Vietnam 1945-1995 (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2011), 221.

Stanley Karnow, Vietnam: A History (New York: Random House, 1994), 696.

Quoted in Nick Kotz, Judgment Days: Lyndon Baines Johnson, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Laws

That Changed America (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2005), 374.

Mary Ann Wynkoop, Dissent in the Heartland: The Sixties at Indiana University (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2002), 54.

Quoted in Lopate and Katz, Rudy Burckhardt, 34.

Ibid., 35.

Anne Waldman, ‘Seeing “The Apple”’. E-mail to the author. September 10, 2012.

As avant-garde filmmaker Matthew Noel-Tod states about The Apple, ‘I like the interplay between “time” – stop frame and live action, the seasons passing – disguised so beautifully and seamlessly, the confident uncluttered photography and framing. The scale and slight unrealness of the apple model. Which seems important to see. The voice / song which drops you in and out of this “fragment”, yet is soothing and anything but fragmentary’. Matthew Noel-Tod, ‘Some thoughts on The Apple.’ E-mail to the author. August 2, 2012.

Anne Waldman, ‘Seeing “The Apple”’. E-mail to the author. September 10, 2012.

Stan Brakhage, ‘Stan Brakhage: Correspondences.’ Chicago Review 47:4 (2001), 29.

Ibid., 36.

Michael Snow, Wavelength. Joyce Wieland & Michael Snow Ltd., 1967. Film.

Michael Zryd, ‘Avant-Garde Films: Teaching Wavelength.’ Cinema Journal 47.1 (2007), 111.

Michael Zryd rightly points out that ‘Wavelength is a film that has suffered from lazy program note summaries, which frequently (mis)describe the film as a ‘45 min zoom across a New York loft,’ which hardly does justice to just how much is going on in the film: a murder mystery, a document of Canal Street (especially the sound mix), a veritable catalogue of light play (filters, flare, black-and-white and color negative, superimposition, etc) (111).

James Roy MacBean, ‘Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group: Film and Dialectics.’ Film Quarterly 26.1 (1972), 32.

Philip Watts, ‘Godard’s Wars.’ L’Esprit Créateur 50.4 (2010), 138.

Peter Gidal, ‘Luxonline.’ Text, Image, Moving Image. Web. 1 Aug. 2012.

Sianne Ngai, ‘The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde.’ Critical Inquiry 31.4 (2005), 814.

Peter Bürger, Theory of the avant-garde (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), xi.

Hans Richter, et al. ‘Ghosts Before Breakfast’. Cinéma Dada. Paris: Re:Voir vidéo : Éd. du Centre Pompidou, 2005. Film.

Emerson, Self-Reliance, 19.

Quoted in Ngai, ‘The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde’, 845.

Ibid., 820.

Anne Waldman, ‘Seeing “The Apple”’. E-mail to the author. September 10, 2012.

John Ashbery, Reported Sightings: Art Chronicles, 1957-1987 (New York: Knopf, 1989), 393.

Mark Silverberg, The New York School poets and the Neo-Avant-Garde: between radical art and radical chic. (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), 7.

Ibid., 13.