The Cottingley Hoax: A Modern Fairy Tale

Evelyn Whorrall-Campbell

Figure 1. Frances and the Fairies. Elsie Wright. July 1917. Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library, Leeds.

Elsie Wright’s first sighting of fairies occurred in the summer of 1917 when, according to her account, these spritely creatures gathered to dance along the bank of the beck near her house in the Yorkshire village of Cottingley. With her young cousin, Frances Griffiths, Elsie would take the first photograph documenting her strange companions in July of this year (fig.1). At nine years old, Frances looked a picture of girlish innocence surrounded by her winged friends. In the image, her head is gently inclined, chin on hand, eyes staring sweetly down the lens. A few months later, Elsie would turn the camera on herself, capturing a comical gnome who grasps her fingertip in his shrunken, spindly hands. (fig.2). Forgotten about for several years, in November 1920 these bizarre photographs made national headlines following their release in the Christmas edition of The Strand. The issue rapidly sold out, public interest stoked by the involvement of an unexpected public figure. To accompany the photographs, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the eminent creator of detective Sherlock Holmes, supplied an article vouching for their authenticity, revealing his involvement in the whole affair alongside friend and fellow fairy enthusiast, the Theosophist Edward Gardner.1 In March the following year, the public would hear how Gardner and Doyle had solicited a further three photographs of fairy sightings from the two girls (figs. 3, 4, 5), as The Strand sought to cash in again on the nation’s appetite for curios and controversy. Although some saw the images as undisputable evidence for fairy life, most readers were amazed at the gullible Doyle and, fascinated at the fakery, speculated on how such photographs could possibly have been produced. Elsie and Frances were unable quell this growing public scepticism. They failed to secure any further photographs, leaving Doyle to publish his book The Coming of the Fairies in 1922 with its hopeful message somewhat dampened by the lack of further photographic proof. By the time Gardner had published his own account entitled Fairies: The Cottingley Photographs and their Sequel in 1945,2 interest had largely ebbed away, relegating the curious business to the realm of fiction and fringe beliefs.3

Generally discussed as an unexplainable historical aberration, an embarrassing blip in the rational progress of modernity, this strange fairy-tale revises numerous premises enshrined in the history of photography.4 What emerges from a retelling of the Cottingley affair is the heterogenous way individuals understood photography and its claims on the real which included familiarity with and reliance upon a range of ontological, technical, gendered and aesthetic discourses. Neglected and derided by scholars as a parochial triviality, these pictures are crucial in telling a different history of the photographic medium, a history which can challenge the ontological assumptions often tacitly subtending existing accounts. The Cottingley photographs and their reception reveal that indexicality, as the dominant historical and ontological assumption made within photo theory, is not an unproblematic analytic in parsing the Cottingley photographs’ contemporary (un)believability. By failing to interrogate the discourse of indexicality as it was constructed by Doyle and Gardner in relation to various precedents drawn from spirit photography, the expert witness, and the evidentiary ‘snapshot,’ one runs the risk of naturalising the discourse itself. The indexical quality of the Cottingley photographs relied upon securing a sexualised and passive image of femininity as embodied in the photographs’ young authors. Doyle and Gardner’s claims regarding photography’s veracity and evidentiary use rested on collapsing Elsie and Frances with their own images, reducing the two girls to aestheticized props in the production of visual proof, much like the very fairies they created. In the Cottingley affair, indexicality was a set of stylistic conventions, conventions which required the stylisation and spectacularisation of both the photographic medium and its subjects, fairies and people alike.

*

Figure 2. Elsie and the Gnome. Frances Griffiths. September 1917. Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library, Leeds.

Figure 3. Frances and the Leaping Fairy. Elsie Wright. August 1920. Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library, Leeds.

Both Doyle and Gardner regarded the girls’ failure to capture any more photographs with their fairy companions a disappointment, if a somewhat inevitable occurrence. In a letter between the two men sent in late June of 1920, Gardner expressed his anxiety about the pubescent impermanence of the girls’ clairvoyant ability, a concern driving his desire to press them to produce more images:

two children, such as these are, are rare, and I fear now that we are late because almost certainly the inevitable will shortly happen, one of them will “fall in love” and then hey presto!!5

While Elsie and Frances were still able to, it was imperative more evidence of fairy existence be secured, of which the strongest form was undoubtedly the photographic document. Doyle confessed as much when explaining his belief in the specific value of Elsie’s images as visual proof to combat contemporary scepticism:

That is why I was so interested in these fairy pictures […] the real thing, the genuine psychic photograph, whether it be of fairies or of some departed friend, is of abiding value. These genuine psychic photographs, when they are sufficiently multiplied, will have their own effect in convincing an unbelieving world.6

Doyle’s reference to ‘psychic photographs’ reveals that he viewed the Cottingley images in light of the more famous fin-de-siecle photographic phenomenon, spirit photography. This was not an inevitable comparison. Although spirit photography was a broad genre encompassing both staid portraits of ghostly apparitions and visceral documents of ectoplasmic excretions, the Cottingley images posed a unique problem within this photographic paradigm. Fairies were not necessarily natural bedfellows of the spirits of the departed, and ethereal though they seemed, common convention dictated that these winged creatures possessed some sensible substance. Unlike most spirit forms, these fairies were visible in this world, i.e. without the aid of photographic equipment, a belief confirmed by the two girls who spoke of spotting their fairy companions playing by the river before turning the camera upon them.7 Doyle and Gardner both struggled to adequately account for the strange sensibility of the fairies, making incomplete claims about the unique psychic ability of the two girls and the material substantiation of their pixie friends. Both men settled on describing the fairies through allusion, deferring explanation in favour of a reliance on oblique metaphors. The problem was the legacy of spiritualist thought applied to the question of fairy materiality. Both Doyle and Gardner borrowed variously from spiritualism’s often contradictory metaphysics. For Doyle, the fairies were compounds of an unknown material which vibrated at a frequency beyond most human perception, visible only to those special few. However, children could somehow (Doyle did not expand further) ‘assist in the strengthening of the etheric bodies,’ which were made of ‘ectoplasm’ or ‘etheric protoplasm,’ so that others, including the camera, could also observe them.8 Gardner went into more detail, ascribing Elsie and Frances’s clairvoyant sight to their use of ‘etheric eyes’ ‘resembl[ing] concave discs behind and around the eyeball, something like a saucer shade behind an electric bulb’ which allowed the seer access to ‘another octave of light’ above normal conscious perception.9

Figure 4. Fairy Offering Flowers to Iris. Elsie Wright. August 1920. Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library, Leeds.

Figure 5. Fairy Sunbath Elves Etc.. Elsie Wright. August 1920. Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library, Leeds.

The question of fairy materiality was problematic for the Cottingley photographs as the veracity of spirit photography had been pegged to the confluence between the mechanics governing the appearance of both apparition and photographic image. The indelible trace of the real left by the interaction of light with the chemically treated photographic plate was easily translated into psychic terminology, where it was the contact between a luminous spirit and the plate which brought about the materialisation of a phantasmal image.10 The techniques of photography themselves, in their mere operation, came to justify the existence of paranormal activity as spiritualists based their claims within specialist discussions of the medium’s operation. Doyle himself had an interest in paranormal image production and had been a member of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) since 1891, a pseudo-scientific organisation founded with the aim of investigating the claims and practices of spiritualists, the strange new Victorian professional straddling scientist, showman, and travelling salesman.11 In 1923 Doyle published The Case for Spirit Photography, an empathic defence of their veracity against recent doubt raised by his SPR colleagues.12 As part of his argument, the author put forward his account of how such photographs were produced:

I think that the evidence is strong that there is on the other side an intelligent control for each photographic medium, whose powers are great but by no means unlimited and who endeavours to give us convincing results each in his own characteristic way. These results are sometimes obtained by actual materialisations, sometimes by precipitations of pictures apart from exposure, sometimes, as I believe, by the superimposition of screens which have the psychic face already upon them, and which give marks as of a double exposure.13

Doyle’s explanation allowed for several different modes of production, accounting for the creativity of the supernatural agent, or ‘control,’ to communicate through the medium in ‘his own characteristic way.’ However, this stated variety described means which were, in fact, quite similar in process, jointly reliant upon a logic of indexicality, the direct trace of the control’s gestures registering on the photographic plate.

Doyle found he needed to adapt this language to account for the Cottingley photographs. The fairies’ relative independence from the camera meant explanations of their photographic appearance had to depart from a metaphysically informed logic of the index as phantasmal trace, and draw instead on what Karl Schoonover identifies as an evidentiary logic of indexicality, based in the camera’s ability to reliably capture the contingent and fleeting world before it.14 Schoonover ties this logic, which he associates with the popularity of ectoplasmic photography in the early twentieth century, to changes in camera technology and public familiarity – the rise of the amateur photographer; lighter, compact and mobile devices; Kodak’s promotion of the snapshot; and the popularisation of photojournalism.15 These changes Schoonover identifies were undoubtedly central to Elsie and Frances’s foray into photography – shot en plein air, on Arthur Wright’s quarter-plate “Midg” camera, the two girls need not have been trained operators to create their images. For Doyle and Gardner, this fact did nothing but support the photographs’ authenticity. Both men worked to play up Elsie and Frances’s naivety, repeating the same refrain; the photographs of July and September 1917 were the first photographs either girl had ever taken, the girls were simple daughters of the artisan class, untrained in the photographic arts such that ‘photographic tricks would be entirely beyond them.’16 Elsie’s experience acquired while working at a Bradford-based photography studio was conveniently forgotten.17

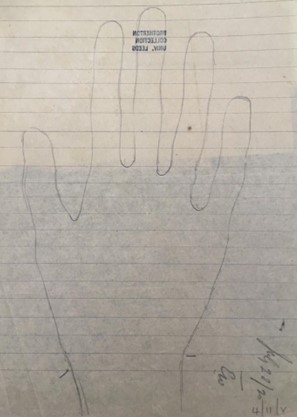

This documentary logic, Schoonover argues, relied upon contemporary scientific methods of investigation and data collection to bolster claims to photographic veracity before a public increasingly familiar with camera technology.18 Such professional posturing was certainly in evidence with regards to the Cottingley affair. In their initial correspondence on the matter, Gardner informed Doyle that the negatives had already been verified by two ‘first-class’ photographic experts who declared them genuine without reservation.19 The plates were also subsequently submitted to two technicians at Kodak who, as Doyle tells readers of The Coming of the Fairies, ‘examined the plates carefully, and neither of them could find any evidence of superimposition, or other trick.’20 Gardner went on his own fact-finding mission to Cottingley in July 1920, taking photographs of the valley itself including the exact locations shown in the background of the girls’ first two photographs. Gardner also secured prints from 1917, the date of the initial photographs, showing Elsie and Frances playing in the beck without shoes and stockings, as they had been when they first sighted their fairy friends. The strangest piece of evidence collected was the sketch Gardner took of Elsie’s hand, a response to criticisms of the image of Elsie and the gnome which pointed to the girl’s distended fingers as indicating photographic fakery (fig.6).21 Doyle reproduced all this evidence for readers of The Coming of the Fairies, down to the exact dates of his correspondence with Gardner under the proviso of transparency and professional integrity – in Doyle’s words, ‘I am laying all the documents upon the table.’22

Figure 6. Outline sketch of Elsie Wright’s hand. Edward Gardner. July 28, 1920. Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library, Leeds.

*

The move from metaphysical to evidentiary explanation appeared to democratise who could discern photographic trickery, i.e. one didn’t have to grasp the mechanics of image production to ‘spot’ the fake. In The Coming of the Fairies, Doyle encouraged the public to adopt the reasoning powers of his famous fictional detective:

In these matters, however, it is necessary to become a Sherlock Holmes. I have had my own experience of faked photographs. It is easy to detect the supercherie.23

However, in practice, the power of discernment remained property of the professional class properly trained to examine photographic evidence. This established a fine line which needed to be carefully tread between professional knowledge and interpretation, and the self-evident transparency of photographic truth. The testimony of trained technicians was central to the claims made by both Doyle and Gardner. In Fairies: The Cottingley Photographs and their Sequel, Gardner relayed an anecdote of a time in which he gave a lecture accompanied by projections of Elsie and Frances’s photographs. The lantern operator subsequently explained that the device used had been one of a specialised kind used to check suspicious signatures and alleged forgeries. Gardner quoted from the now-convinced man:

Some of us were sure your photographs were faked and that when the first one came on, the fake would be shown up all round – and you’d clear! The boys up in the gallery were all ready for it, but we were done. Those photographs are straight; nothing else could have stood up to that lantern. Looks as if I have to believe in fairies!24

Here, the camera was a tool in the Edwardian information economy, capturing and isolating the confusion of an undifferentiated world, allowing the expert witness to train his eye on the meaning spelled out by the referential traces left from past events. The unique advantage of the camera was its focused vision, rendering the world in such detail that each surface could be carefully inspected for signs of truth.25 The ‘camera’ here refers to the entire photographic apparatus itself, as the various techniques possible in the printing process were central to how these ‘professional’ spectators like Gardner and Doyle accessed the photographic document. In a six-page report to Doyle, reprinted in full in The Coming of the Fairies, Gardner stressed that he ‘need hardly add that enlargements were made [of the negatives] and subjected to searching examination – without any modification of opinion.’26 These devices, such as enlargement, or retouching (performed by independent technician Mr. Snelling to compensate for the over-exposure of ‘Frances and the Fairies’)27 were framed as neutral actions capable of bringing out a reality inherent if currently unobservable in the image, a way to enhance the existing details of the photograph so that its truth or trickery could be discerned.

Enlarging the negatives could make such surface details greater in scale yet, unlike a telescopic device, which could seemingly ‘enter’ an image and bring greater clarity through a greater depth of field, a blurred photograph could not be brought into focus through a larger print.28 Enlargement preserved the surface, changing only the scale of existing visual information. Thus, anything on the surface of the print would be enlarged too, including possibly obfuscating scratches and blemishes. Enlargement thus may have been instrumental in helping identify certain signs of photographic fakery, namely those associated with superimposition or double exposure, as residues of these techniques left on the plates would become more obvious at a greater scale. As these signs were not evident upon repeated examination by independent professionals, Doyle and Gardner’s confidence in the veracity of the images grew. However, in their fixation on surface deceptions, these two men missed a trick, for Elsie and Frances did not resort to such elaborate means to produce their fairy photographs. Professionalised ‘indexical looking’ did not equip Doyle and Gardner to see beyond the surface trace.

Elsie had pursued an interest in fine art after leaving secondary education and took classes at the Bradford School of Art before receiving employment at Gunston & Co Photographers. Elsie deployed this creative talent in service of her trickery. As Frances Griffiths later disclosed, her elder cousin had copied the fairies from pictures in her ‘Princess Mary’s Gift Book,’ a popular children’s book published in 1914.29 Elsie’s fairies, hand-drawn on flimsy card, were propped up using hatpins and carefully arranged to create the photographs’ artful compositions.30 The various experts called upon to verify the photographs failed to spot this simple trick. Mr Snelling, one of the experts initially consulted by Gardner, directly countered any suggestion of the sort, as the Theosophist wrote to Doyle in July 1920:

Mr Snelling’s report on the two negatives is positive and most decisive. He says he is perfectly certain of two things connected with these photos, namely: 1. One exposure only; 2. All the figures of the fairies moved during exposure, which was “instantaneous.” As I put all sorts of pressing questions to him, relating to paper or cardboard figures, and backgrounds and paintings, and all the artifices of the modern studio, he proceeded to demonstrate by showing me other negatives and prints that clearly supported his view.31

The experts from Kodak also failed to ‘find any evidence of superimposition, or other trick,’ convinced that they would have to ‘set to work with all their knowledge and resources’ to reproduce a similar photographic result to that achieved rather straightforwardly by Elsie in her garden.32

However, the fairies’ lack of dimension did not fool all viewers, as Major John Hall-Edwards, a pioneer of medical X-ray use, perceptively pointed out in the Birmingham Weekly Post:

The picture in question could be ‘faked’ in two ways. Either the little figures of the fairies were stuck upon a cardboard, cut out and placed close to the sitter, when, of course, she would not be able to see them, and the whole photograph produced on a marked plate.33

Hall-Edwards’s scepticism made little difference to Doyle and Gardner’s assessment, to the extent that Doyle felt able to reproduce Hall-Edwards’s scathing comments in The Coming of the Fairies. Doyle had an easy answer to the problem of the creatures’ lack of shadow – it was the ‘faint luminosity’ of their ‘etheric protoplasm’ which altered the casting of shade.34 Hall-Edwards himself could not confidently identify the method by which the images were faked, speculating that the use of cardboard figures was only one of two possible means of trickery. Other newspaper sceptics also struggled to identify Elsie and Frances’s secret, as was the case for the author of an article in the Westminster Gazette, who asserted that the photographs were studio composites, suggesting ‘with confidence that the child in “Frances and the Fairies” was not taken under outdoor conditions at all.’35

Although Doyle and Gardner relied upon the discourse of indexicality to support their arguments for the Cottingley photographs, their believability lay less in the indexical trace than in the literal surface limitations of the medium. Doyle and Gardner could plausibly deny the existence of any kind of trickery, and experts plausibly agree with this denial, because the two-dimensionality of the fairy figures was masked behind, or absorbed within, the two-dimensional nature of the photographic image. Here is an important adjunct to histories of photography, for indexicality was unable to make meaningful sense of the faked fairies, being ‘real’ in the sense of ‘real’ illustrations placed before the camera. The point here is that the Cottingley photographs’ hold on the real was in part through the paradoxical de-realisation of everything in its two-dimensional frame. For even to critically motivated eyes, such as the writer for the Westminster Gazette, the backdrop of the glen appeared as unreal as the fairies themselves. Thus, why could the reverse not be as true – if the flat image of the beck was real, then perhaps the fairies were too?

Edward Gardner recognised this particular fungible facet of photographic realism when he first visited Cottingley to take evidential photographs of the beck itself. These images served the express purpose of refuting that the beck was merely a flat studio backdrop to lend credence to the fairy photographs as a whole. Gardner had Elsie pose in various locations near the stream and small waterfall to demonstrate that the landscape indeed extended beyond the frames of the girls’ photographs. Here, Gardner was subscribing to the camera’s documentarian utility, i.e. its unique capacity to capture the contingency of the glen, a vista far beyond human attempts at pastoral verisimilitude. As Gardner tried to argue, these fairy photographs were not aesthetic artefacts, objects of human design, but were consistent with the snapshot, that amateur product of a desire to simply capture a quotidian moment as it was.

The importance of a photograph’s unauthored background to ontological investments in the medium’s veracity has proved lasting – in What Photography Is, James Elkins makes claims as to the medium specificity of photography as distinct from painting according to the contingency of the photographic backdrop, what he terms the ‘surround.’36 For Elkins, the central difference between these two art forms lies in the periphery, a difference mapped onto a terminological distinction crucial to his argument, wherein:

The surround, as I like to call it, is not the same as the background that painters know, because backgrounds are put in mark by mark and are therefore always noticed, always intended […] The surround is something different – it is, I think, one of the best names for the gap between painting and photography.37

For Elkins, the surround is photography’s point of uniqueness. Unlike the background of a painting, where details are only seemingly innocuous, having been deliberately placed there by the artist’s own hand, the surround is pure contingency, any detail or mark a pure accident allowed in by the medium’s indiscriminacy. Yet, as historian Kate Flint argues, this distinction is insensitive to the history of photography’s technological development. Flint pursues this line of argument via the invention of flash photography in the 1880s, whereupon the new technology not only made it possible to illuminate the small details of domestic interiors, but also produced an aesthetic of illumination wherein the new visibility of these background details produced their own especial meaning and value.38 For Flint, the predominance of flash photography in documenting previously unpicturable Victorian slums lent the visual play of darkness and light a poetic overtone – the humanitarian display of urban depravation before previously indifferent eyes. To apply Flint’s thinking to the question of interwar photography, the association of the camera with the contingent was not pre-determined, but the result of technological development in shutter speeds, camera portability, light receptivity, and careful discursive framing.

Gardner’s photographs of the Cottingley beck were an exercise in producing this effect of contingency, an attempt to circumvent the problem of surface through demonstrating the three-dimensional reality of the beck itself. With his camera trained on the rich detail of the countryside, Gardner emphasised the beck’s spontaneous beauty far beyond human creativity. He paid particular attention to the waterfall in the beck, just visible in the background behind Frances in the first fairy photograph. On his initial visit to Cottingley, Gardner took a picture of Elsie leaning against the bank of the beck, posing nonchalantly in smart coat and peaked hat (fig.7). In the image, the toes of her leather boots rest on the stony riverbed as the clear waters of the stream flow around her feet. A photograph taken seconds later by Gardner panned along from the first to take in more of the beck, showing the waterfall foaming into the pool below, Elsie’s booted foot just visible in the bottom-right corner (fig.8). This framing was deliberate, or in other words, this pan was a pointed visual elaboration of the aesthetic constraints of the frame. For Gardner has Elsie ‘step’ into the initial photograph’s backdrop to prove its depth. What to Elkins is the neutral, spontaneous surround, is here the very deliberate decision taken by Gardner to reproduce the innocuous background details of the beck to ground the existence of Cottingley’s spritely inhabitants.

Figure 7. Elsie leaning against the beck where ‘Frances and the Fairies’ was taken. Edward Gardner. July 1920. Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library, Leeds.

Figure 8. View of the beck and waterfall where ‘Frances and the Fairies’ was taken. Edward Gardner. July 1920. Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library, Leeds.

*

The slow shutter speed on Gardner’s camera rendered the waterfall’s rushing torrent as a single blurry white streak. Showing the beck was important to his efforts to demonstrate the reality of the backdrop – a gushing waterfall could not be replicated as a studio set piece. The waters’ rapid movement testified to the camera’s documentary capacities, capturing the fleeting moments of nature – the trickle of water, the flap of fairy wings. For both Doyle and Gardner maintained that these images of pixie creatures were fortuitous, momentary snapshots of fragile beings which could vanish as quickly as they came. Extensive captions in The Coming of the Fairies detailed the events of each photograph’s production, emphasising the spontaneous nature of the images, as evident in the caption for the 1917 photograph known as ‘Elsie and the Gnome’:

Elsie was playing with the gnome and beckoning it to come on to her knee. The gnome leapt up just as Frances, who had the camera, snapped the shutter.39

Like the beautiful beck surroundings, the presence of motion testified to the photographs’ veracity, again producing the association between the camera and the contingent which strengthened its documentary claims. However, this claim to motion was not left uncontested by the photographs’ critics. In the literary magazine John O’London’s Weekly a Mr Maurice Hewlett took issue with the representation of motion in the fairy photographs:

never by any chance does the photograph of a running object in the least resemble a picture of it. […] So infinitely rapid is the action of light upon the plate that it is possible to isolate a fraction of time in a rapid flight and record it. […] Now the beings circling round a girl’s head and shoulders in the Carpenter [sic.] photograph are in picture flight and not in photographic flight […] They are in the approved pictorial, or plastic, convention of dancing […] the figures are not moving.’40

Hewlett’s commentary made clear that the issue of contention was precisely the photographic convention of motion as represented in the still image. He drew a distinction between ‘picture flight’ and ‘photographic flight,’ the main point being that the pictorial convention of motion must visually illustrate movement due to being in fact motionless, whereas in photographs, moving objects are in fact stilled, caught in an isolated second by the snap of the shutter. Edward Gardner responded to Hewlett’s criticism with barely disguised disdain:

Mr Hewlett makes the astonishing statement that at the instant of being photographed it is not in motion […] Of course the moving object is in motion during exposure, no matter whether the time be a fiftieth or a millionth part of a second […] And each of the fairy figures in the negative discloses signs of movement.41

Hewlett and Gardner’s clash demonstrate that their belief or disbelief in fairy life was displaced onto a contest over the interpretation of photographic conventions and expectations for the rapidly evolving medium. It is revealing that disbelievers chose to locate their scepticism in a detailed debunking of the photographs themselves, turning a debate around the existence of fairy life into one centred around the capacities of the photographic medium. Hewlett’s reference to ‘photographs of beings in rapid motion,’ especially ‘horses racing’ recall the photographic studies by Eadweard Muybridge of animal locomotion, completed between 1872 and 1884, the most famous of which being his series ‘The Horse in Motion.’ Echoes of the conventions of speed built by Muybridge, the man who made ‘time stand still,’ sound in Hewlett’s statement: ‘[s]o infinitely rapid is the action of light upon the plate that it is possible to isolate a fraction of time in a rapid flight and record it.’42 Muybridge and his horses were also a particularly apt reference for Hewlett, as the former’s equestrian studies disillusioned painterly conventions, demonstrating the physiological impossibility of the elongated leap known as the ventre à terre depicted in running horses, something Hewlett attempted in his distinction between the stylised and static ‘picture flight’ of the fairies, and the conventions expected in the photograph.43 Although there is no direct evidence that Hewlett was consciously referencing Muybridge, the numerous resonances indicate the development of a set of sophisticated expectations regarding the limits of photographic representation and its application to the Cottingley photographs before an interested public.

The fairies depicted in the Cottingley photographs presented an aesthetic problem which picked at the images’ documentary claims – contemporary commentators pointed out the strikingly fashionable nature of the winged creatures, their appearance conventional with popular depictions of fairy life an odd coincidence for otherwise otherworldly creatures.44 There was also the question of their bizarre pictorialism – a question which not only plagued the whimsical figuration of the fairies themselves, but also alighted on the deliberateness of photographic composition. Why, if the fairies had appeared to Frances by the beck, was the young girl looking straight down the lens, staid and still, rather than gazing in wonder at her tiny companions? Why, as Major Hall-Edwards pointed out in the Birmingham Weekly Post, is Frances ‘posing for the photograph in the ordinary way’?45 The girl’s composed comportment seemed typical of portraiture, but unexpected in what purported to be a documentary snapshot. Everything appeared a little too conventional within the Victorian genre of fairy-related media and merchandise, a market stimulated by cheapening manufacturing methods, mandatory primary education, rising disposable incomes, and the concretisation of the ‘child’ as a distinctive stage within psychological and physical development requiring protection. Familiar with this trope, members of the public received the Cottingley photographs less as indexical documents evidencing fairy life, but as visual spectacles, commodities for circulation within the interwar media economy.

As historian Alex Owen identifies, the ‘modern’ depiction of fairies as beautiful feminine creatures with butterfly wings was first popularised in the mid nineteenth century by a loose group of artists, retrospectively termed the Victorian fairy painters, who first popularised the ‘modern’ fairy depicted as a beautiful feminine creature with butterfly wings.46 The Victorian fairy painters were a loose collection of male artists including Richard Dadd, Joseph Noel Paton and Richard Doyle, Arthur Conan Doyle’s own grandfather, who drew inspiration from Shakespeare’s The Tempest and A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream to paint large canvases depicting rich scenes of fairyland. As the Princess Mary Gift Book from which Elsie copied her fairies attests to, these delicate winged beings had become an unavoidable motif in children’s media by the turn of the twentieth century. The Cottingley photographs were part of this strange patrilineage, bringing interwar Victorian nostalgia together with a modern medium for mass-production.

Links between the spectacle of fairy life and the spectacle of photography were not new. The fairy as an enchanted figure able to express the unique wondrous quality of photography was deployed within the medium’s early promotional rhetoric. In The Pencil of Nature, inventor of the calotype, William Henry Fox Talbot describes his disappointment with the copying devices available to him, an amateur draftsman attempting to capture Lake Como’s beauty in a sketch. He bemoans the poverty of his drawing in comparison to the infinitely more pleasing ‘fairy pictures’ seen on the ground glass lens of the Camera Obscura.47 ‘Fairy pictures’ because they were similarly fleeting and fragile, merely ‘creations of a moment, and destined as rapidly to fade away.’48 Yet, these were ‘fairy pictures’ also because there was no human agent behind their creation – such pictures were the product of an automatic process, the ‘pencil of nature’ drawing itself without the guidance of a human hand. For art historian Steve Edwards, this invocation of natural magic in the form of fairies was not an isolated rhetoric, but borrowed from the language of industrial capitalism and the mechanisation of labour processes in Fox Talbot’s own century. Industrialist Charles Babbage described his steam-powered loom in similar terms, wherein the engine ‘with almost fairy fingers, entwines the meshes of the most delicate fabric that adorns the female form.’49 For Edwards, the presence of the fairy in both the discourses of manufacturing and photography was a signifier of an attempt at the suppression of skilled labour, the concealment of both artistic and productive labour behind the rhetoric of mechanical magic. This magical language was indeed its own marketing strategy, designed to induce wonder and produce interest.

As Edwards identifies, the stake for these claims of automation was the securitisation of property. The artist, as visible author of their work through their singular marks of making, their signature, could make an uncontested claim to ownership. The automated photograph, authored by the technology itself, modified such claims. Soon into their involvement with the Cottingley affair, both Doyle and Gardner became concerned with questions of copyright. In a letter sent by Edward Gardner to Polly Wright in early June of 1920, the Theosophist propositioned Elsie’s mother with his own business deal:

A good many people are asking for copies and I can supply some. But I thought it right to put it to you and perhaps you will see Miss Elsie, that it will be wise to “copyright” the photographs first. I can do this easily enough here but it should be done with the owner’s consent. Anyone getting a copy now, as it stands, could send the same to a paper and probably obtain money for it […] if you approve I will get the photo copyrighted […]50

Gardner’s intentions were obvious: in a letter to Snelling, the photographic expert who had verified the plates, he revealed his desire to mass produce and sell prints of the photographs.51 Gardner informed Arthur Wright of this plan and his intention to put aside a small amount from the sales to be given to the girls’ every year, although it is unclear if Elsie and Frances ever received any royalties.52 Even prior to copyrighting the photographs, Doyle and Gardner were protective of their discovery and financial interests. In a letter to Doyle sent in August 1920, Gardner expressed concern that the photographs seemed to already be on sale, and recommended they contact the vendors immediately to inform them ‘that it was illegal and to recall all they could.’53 The Cottingley photographs were bound to be highly lucrative, and it was necessary for both men to swiftly secure their monopoly.

Gardner and Doyle’s attempt to secure copyright for the Cottingley photographs, to transform them into property of their promoters for reproduction and commodification, relied upon the abstraction of Elsie and Frances, removing their claim to ownership by negating their authorship. Belief in the photographs’ authenticity aided this abstraction by making the girls disappear behind the technology, the camera itself as proper author in its automation of image production. However, it was the aesthetic quality of Elsie and Frances’s photographs, their careful composition, Elsie’s delicate draftsmanship, which made the photographs such appealing objects. The aesthetic question could not be divorced from the claims made by believers and non-believers alike, a point also made by Steve Edwards: “[a]esthetic questions were integral to the business of photography and to the objective image elaborated on by men of science.”54 Yet, as Edwards’s statement implies, the aesthetic devices deployed by Elsie and Frances, despite indicating their artistry, only furthered their alienation from the objects of their own making. For they became enfolded into their own aesthetic, their consistency with an expected romantic image of rural England propping up interest in their photography whilst securing their passivity. The aforementioned financial transactions between Doyle, Gardner, Elsie and Frances were not wages due labour, but an exchange which produced the girls as commodities, products experiencing a kind of seriality akin to their fairies, copied from a mass-produced children’s magazine.

Rather than agents of their own image, Elsie and Frances found themselves trapped within the same spectacularising frame surrounding their own fairy creations. To secure the images’ proof claims, it was necessary that both girls repeatedly perform the appearance of girlish passivity they had playfully presented in the Cottingley photographs. In the model of spirit mediums, which as Alex Owen identifies were frequently pre-adolescent girls, Elsie and Frances’s etheric ‘gifts’ were tied to their youthful docility.55 Gardner wrote to Irish author Henry de Vere Stacpoole, describing his August excursion to Cottingley to extract more fairy photographs from Elsie and Frances, whereupon he ‘kept them in as playful and irresponsible mood as possible though they entered into it with all the seriousness of children taken seriously.’56 By this time Elsie was nineteen years old, having been sixteen when she took the first fairy picture in 1917. Yet it remained important to characterise her as an unsophisticated infant, caught in play without pretensions, for her transparency was tied to the transparency of her photographs as automatic reproductions of the world without interference.

Youthfulness was itself a shorthand for innocence, which meant not only innocence in matters of photographic deception, but also in the other ‘sins’ of the adult world. Doyle and Gardner’s fears about Elsie and Frances’s maturation were confessed in their worry that ‘one of them will “fall in love”’,57 clearly spelling out how the girls’ sexuality and future desires were threats to the purity deemed necessary for fairy sightings. Although, this innocence only ran one way, for Elise and Frances’s performance of sexual purity made them objects of fetishism and attraction – the effacement of Elsie and Frances as agents under the rhetoric of feminine passivity and photographic automation was paradoxically reliant upon the overt presence of the girls as ‘image.’58 It was necessary for them to visibly perform their own passivity, accessories to their photographs, but not their authors. Gardner made them accompany him on his lecture tours to stand on stage clutching bouquets of flowers.59 Photographs of Elsie and Frances costumed in flowing dresses befitting the fantasy of a rural girlhood appeared in The Coming of the Fairies, designed to extend the magic of the fairy pictures into an imagined performance of the girls’ everyday lives. To secure the truth claims of the unmediated photograph, Elsie and Frances in their hyper-visibility had to become visibly transparent, simply passive channels through which the truth of the world could pass. The popular press continued the infantilisation of Elsie and Frances in articles which bordered on the fetishistic. The Westminster Gazette published an interview with Elsie in the January of 1921 wherein the author, despite acknowledging Elsie’s age and mentioning the various occupations she held since leaving school, continued to call Elsie and her cousin Frances children. The paper seemed keen to conjure up an image of a vulnerable young girl, printing a comment from her mother Polly that ‘Elsie was not robust’ and one from her old schoolmaster, who described her as ‘dreamy.’60 Further embellishment to this image was provided by the author’s description of the young woman as ‘a tall, slim girl, with a wealth of auburn hair, through which a narrow gold band, circling her head, was entwined.’61

This romanticised image of girlish innocence was actualised in a photograph taken for an unnamed newspaper early in 1921. Polly, Elsie’s mother made reference to the image in a letter to Gardner, where she explains how she had refused the photographer permission to photograph her daughter, ‘but he must have got one somewhere for it was in one of the papers next day, it was the one where she is leaning against a tree with flowers in her hair…’62 As Polly describes, this image depicted Elsie leaning louchely against a tree trunk, dressed in a long white smock cinched at the waist, her flowing locks crowned with a ring of flowers. Her comportment, both sartorial and postural, with extended bare neck and averted gaze, presented an image of sexualised passivity. Both Doyle and Gardner, despite their stated fear of the girls’ future romantic-sexual desires, would similarly fetishise Elsie, making her an object of their fantasies of a romantic rural England. Gardner himself would turn his camera on Elsie more than ten times whilst ostensibly gathering corroborating images of the beck scenery, making the young woman as much a part of the unsullied aesthetic of the Yorkshire countryside as the surrounding flora and fauna.63 Both Doyle and Gardner wrote to Elsie frequently, plying her with gifts and concocting a plan to put together a wedding dowry out of the proceeds from the sales of The Coming of the Fairies.64 Despite imagining Elsie’s bridal future, the men continued to infantilise her – Doyle wrote to Elsie in June of 1920, expressing that he would ‘send you tomorrow one of my little books for I am sure you are not too old to enjoy adventures.’65 As Doyle and Gardner attempted to push back the horizon of Elsie’s sexual maturity they, alongside the popular press, they paradoxically sexualised Elsie, producing the image of a child as receptive, passive, penetrable – the ideal mediatic channel for fairy impressions to travel through into the adult world.

Central to the veracity of the Cottingley photographs was this reduction of Elsie and Frances to their representations, props designed for the production of visual proof, much like the very fairies they created. Yet, an examination of the Cottingley photographs without the stifling focus on their truth value reveals them to be the product of an imaginative mind with very different intentions than those of Arthur Conan Doyle and Edward Gardner. The attentive arrangement of the fairies, Frances’s direct gaze and slightly tilted head garlanded with flowers, reveals the care and deliberation with which Elsie composed this portrait of her cousin (fig.1).66 The images she constructed demonstrate her attempt to both fulfil a childhood fantasy, and simultaneously signal her maturity through her knowingness in deception. In a 1972 Daily Express interview Elsie told the interviewer: ‘Frances said she’d got into trouble for lying. “But grown-ups lie” Frances said. “They tell you about Father Christmas and show his picture, and then you find out there isn’t a Father Christmas.”’67 Elsie’s mention of the ‘grown-ups’ lie’ was a playful allusion to her reversal of this state of affairs via her own pantomime figures. She was engaged in an imaginative re-staging of a Victorian vision of fairy life through parodying adult trust in the authenticity of photography.

There existed a continual tension between Elsie as agent and Elsie as subject from when Gardner first acquired the two initial photographs of fairies in February 1920. The discourses of mechanical indexicality and infantile innocence turned upon the girl who had knowingly parodied them to deny her control over her creation and her image. Elsie’s only option was to exercise her agency defensively, through refusing to comply with the image of herself held by others. In the Westminster Gazette article, her coy avoidance of questions accompanied with laughter and knowing smiles, disturbed the pall of innocence drawn around her by the article’s author.68 However, the untainted image of youth seized upon by Gardner remained preserved and inescapable in Elsie’s photography, the enigmatic spell of which continued to keep the public enraptured throughout the rest of the twentieth century. Elsie remained hyper-present as the innocent subject of her images, not as their imaginative maker. For, even whilst the aesthetic quality of the Cottingley photographs would seem to betray their inauthenticity, Gardner and Doyle relied upon this to produce a particular mode of English beauty, supported by their fashioning of Elsie and Frances into handmaidens of a virginal and unsullied rural seclusion.

*

Immediately following the initial publication of the Cottingley photographs in The Strand, the press was flooded with imitation images. Even though Elsie and Frances did not reveal the exact means of their deception until the 1980s, members of the public joyously seized the opportunity to create fairy images of their own. Some were highly sophisticated, presenting fairies in more technically demanding poses than Frances and Elsie had managed, such as flight. A few revealed the secrets of their fakery, careful to state that they ‘[did] not claim to possess any occult vision.’[69 The majority however, were ambiguous in their presentation. A photograph of a couple with a large fairy flying over their heads printed in The Daily Mail left its origins to guesswork, asking readers: ‘Where did the “fairy” seen above the two sitters come from?’70 One photograph reproduced in The Observer in 1921 sent in by a ‘local photographer’ was accompanied with an anonymous note attached to the negative which confirmed it was an ‘actual photo[graph] of flying fairies’ despite the fact that the image itself seemed unbelievable even by the standards of Doyle and Gardner, with the outsize scale of the fairy misaligned with the raised gaze of the female spectator indicating the use of superimposition.71 Clearly, the value of these images for their creators and audience lay in their imaginative parody of the conventions of realism, wherein truth and falsity were blurred through the act of creative play. The nature of these photographs could not be easily resolved as through a binary classification as either evidential or artistic documents, belonging instead to the marketplace of photographic spectacle, wonderous for both purported content and realised effects.

The public response to the Cottingley images mirrors the complex historical claims made by the fairy pictures, pictures which challenge the dominance of indexicality as an analytic within photo theory, and open onto a more heterogenous horizon of possible understandings and expectations of the photographic medium during the British interwar. Claims for and against realism rested on numerous ontological, technical and aesthetic discourses, including but not limited to the indexical, claims which also rested on a matrix of other social and epistemological assumptions regarding the gender of creative labour and agency. As The Daily News put it to their readers in 1922, the reality of the Cottingley fairies rested not in the ‘hard facts’ pursued by those invested in debunking, but in ‘the mind and the imagination’ of all who saw their image.72 It is worth taking such imaginative reality seriously, for all it can reveal about how claims for photography were reconstructed during a key period in the medium’s history, where change in camera technology, cheapening reproduction, and widening accessibility, refigured a broad range of expectations and interactions, where ontological claims about the medium were often contradictory and incomplete, especially when faced with five small photographs of fairies taken by a teenager and her young cousin in the Yorkshire village of Cottingley.

Evelyn Whorrall-Campbell is a PhD Candidate in the Centre for Film and Screen Studies at the University of Cambridge. Their academic work attends to media theory, the politics of representation, and histories of sexuality and gender across the twentieth century.

Notes

Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘Fairies Photographed: An Epoch-Making Event…Described by A. Conan Doyle’, The Strand Magazine 60 (1920), 462-468.

Edward L. Gardner, Fairies: The Cottingley Photos and Their Sequel (London: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1945).

For examples see, Christopher Neve, ‘But Are They Happy in Fairyland?’, Country Life (23 December 1971); Psychic News (27 February 1971); Michael Parkin, ‘Magic of the fairy prints – that nobody can deny’, The Guardian (8 September 1975), 6; ‘Interview with the “Fairy-Lady”’, Woman (25 October 1975), 42-45.

Perhaps because of the liveliness of popular interest, scholarly attention to this incident has been severely limited. The two main texts on this subject, by Joe Cooper and Geoffrey Crawley, a psychical researcher and a photographic expert respectively, are largely works of investigative journalism. See Joe Cooper, The Case of the Cottingley Fairies (London: Robert Hale, 1990); Geoffrey Crawley, ‘That Astonishing Affair of the Cottingley Fairies’, published in 10 parts in The British Journal of Photography, (1982-1983). For scholarly analyses, see Nicola Bown, ‘“There Are Fairies at the Bottom of Our Garden”: Fairies, Fantasy and Photography’, Textual Practice, 10.1 (1996), 57–82; Alex Owen, ‘“Borderland Forms”: Arthur Conan Doyle, Albion’s Daughters, and the Politics of the Cottingley Fairies’, History Workshop Journal, 38 (1994), 48–85.

Letter from Edward Gardner to Arthur Conan Doyle, 25 June 1920, B15575, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/6, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library.

Quoted in John Lamond, Arthur Conan Doyle: A Memoir (London: John Murray, 1931), 227.

Arthur Conan Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 1st edn (London: Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, 1922), 37.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 9, 37–38.

Gardner, Fairies, 26.

Jennifer Tucker, Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in Victorian Science (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2005), 93.

For more on Doyle’s investment in spiritualism, and the impact of WWI on psychic beliefs, see Jay Winter, Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning: The Great War in European Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 54–76.

Arthur Conan Doyle, The Case for Spirit Photography (New York: George H. Doran Company, 1923).

Doyle, The Case for Spirit Photography, 59.

Karl Schoonover, ‘Ectoplasms, Evanescence, and Photography’, Art Journal, 62.3 (2003), 30–43.

Schoonover, p. 36.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 3, 18, 58, 64; Gardner, 17.

Geoffrey Crawley, ‘That Astonishing Affair of the Cottingley Fairies: Part Nine’, The British Journal of Photography, 1983, 332.

Schoonover, 36.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 16–17.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 23.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 24–25.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 20.

Quoted in Lamond, 227.

Gardner, 23.

Kitty Hauser, Shadow Sites: Photography, Archaeology, and the British Landscape 1927-1955 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 58.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 33.

Geoffrey Crawley, ‘That Astonishing Affair of the Cottingley Fairies: Part Two’, The British Journal of Photography, 1982, 1411.

For more on telescopic devices and early cinema, see Jan Holmberg, ‘Closing In: Telescopes, Early Cinema, and the Technological Conditions of De-Distancing’, in Moving Images: From Edison to the Webcam, by John Fullerton and Astrid Söderbergh-Widding (Sydney: John Libbey & Co, 2000), 83–90.

Frances Griffiths and Christine Lynch, Reflections on the Cottingley Fairies (Belfast: JMJ Publications, 2009), 21; J.M. Barrie and others, Princess Mary’s Gift Book (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1914).

Geoffrey Crawley, ‘That Astonishing Affair of the Cottingley Fairies: Part Four’, The British Journal of Photography, 1983, 66.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 21–22.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 23.

Quoted in Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 55–56.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 37–38.

A. H. W, ‘“Fairy” Photographs: A Challenge to Sir A. Conan Doyle. “Fake” or Truth?’, Westminster Gazette, 27 November 2020.

James Elkins, What Photography Is (New York: Routledge, 2011).

Elkins, 116–17.

Kate Flint, ‘Surround, Background, and the Overlooked’, Victorian Studies, 57.3 (2015), 457–59.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 39.

Maurice Hewlett, ‘Fairies in Photographs’, John O’London’s Weekly (London, 18 December 1920), 359. Hewlett refers to Carpenter here as that was the pseudonym Doyle chose to give Elsie Wright in his article to hide her identity from the public.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 64.

Philip Prodger, Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the Instantaneous Photography Movement (Stanford: Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University in association with Oxford University Press, 2003).

Philip Prodger, ‘In the Blink of an Eye: The Rise of the Instantaneous Photography Movement, 1839-1878’, in Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the Instantaneous Photography Movement (Stanford: Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University in association with Oxford University Press, 2003), 28.

Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 19.

Quoted in Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, 55.

Owen, ‘“Borderland Forms”: Arthur Conan Doyle, Albion’s Daughters, and the Politics of the Cottingley Fairies’, 52.

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature (London: Longman, 1844), p. 4; See also Steve Edwards, The Making of English Photography: Allegories (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), p. 24.

Fox Talbot, p. 4.

Quoted in Edwards, p. 40.

Letter from Edward Gardner to Polly Wright, 4 June 1920, G10 B15574, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/7, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library.

Letter from Edward Gardner to Snelling, 14 December 1920, G56 B15620, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/7, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library.

Letter from Edward Gardner to Arthur Wright, 18 December 1920, G61 B15625, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/7, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library.

Letter from Edward Gardner to Arthur Conan Doyle, 12 August 1920, D13 B15556, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/6, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library.

Edwards, p. 2.

Owen, ‘“Borderland Forms”: Arthur Conan Doyle, Albion’s Daughters, and the Politics of the Cottingley Fairies’, pp. 72–73; For more on the gendering of spirit mediums, see Alex Owen, The Darkened Room: Women, Power and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England (London: Virago Press, 1989).

Letter from Edward Gardner to H. de Vere Stacpoole Esq, 25 June 1920, B15575, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/6, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library. For examples, see Doyle, The Coming of the Fairies, pp.23-25, 37, 51.

Letter from Edward Gardner to Arthur Conan Doyle, 25 June 1920, B15575, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/6, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library.

This notion of the dual life of the child as both social actor and ‘representation’ or ‘device’ is further explored, in specific relation to the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in Carolyn Steedman, Strange Dislocations: Childhood and the Idea of Human Interiority, 1780–1930 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), p. 79.

Griffiths and Lynch, p. 70.

‘Do Fairies Exist? Investigation in a Yorkshire Valley. Cottingley’s Mystery. Story of the Girl Who Took the Snapshot’, The Westminster Gazette, 12 January 1921.

‘Do Fairies Exist? Investigation in a Yorkshire Valley. Cottingley’s Mystery. Story of the Girl Who Took the Snapshot’.

Letter from Polly Wright to Edward Gardner, letter undated, B15792, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/6, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library. A copy of a photograph matching Polly’s description remains in the Brotherton Collection at the University of Leeds archives. This image is striking in its resemblance to late-Victorian photographs of children, such as those taken by Lewis Carroll. See Carol Mavor, Pleasures Taken: Performances of Sexuality and Loss in Victorian Photographs (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995).

See the collection of Edward Gardner’s photographs held in the Brotherton Collection at the University of Leeds Library, especially those listed under BC MS Cottingley Fairies/6/2, and BC MS Cottingley Fairies/6/4.

In a letter to Arthur Wright, Doyle wrote: ‘I hope to get a small wedding dowry for Elsie from the fairies. Also for the little girl.’ Letter from Arthur Conan Doyle to Arthur Wright, 3 August 1920, B16749, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/6, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library.

Letter from Arthur Conan Doyle to Elsie Wright, 3 June 1920, B16750, BC MS Cottingley Fairies/5/6, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library. See also, Bown, ‘“There are fairies at the bottom of our garden”’, p.66.

This argumentation agrees with Nicola Bown’s assertion that the Cottingley photographs need to be seen as ‘art photographs’, an experiment with representation to be placed ‘in the domain of the aesthetic rather than the evidential.’ Bown, p. 21.

Crawley, ‘That Astonishing Affair of the Cottingley Fairies: Part Nine’, p. 337.

‘Do Fairies Exist? Investigation in a Yorkshire Valley. Cottingley’s Mystery. Story of the Girl Who Took the Snapshot’.

‘The New Fairyland: Latest Pastime for Amateur Photographers’, B15440, Leeds Archive of Vernacular Culture Collection, Brotherton Collection: Leeds University Library.

The Daily Mail [undated clipping], B15440, LAVC/FLF/11/1/4, Leeds Archive of Vernacular Culture Collection: Leeds University Library.

The Observer (11 February 1921).

‘The Real Fairies’, The Daily News, 30 December 1922