Pseudo-Cinema

Evan Calder Williams

The only real difference between the paintings of apes and my complete cinematographic work to date is its possible threatening meaning for the culture around us, namely, a wager on certain formations of the future.

—Guy Debord, Potlatch 29 (1957)1

I. What is Left to be Done

A peculiar declaration to start: Guy Debord both did and did not make six films, at least according to the films themselves. From start to finish, his cinematic practice consisted of persistent activity within a form declared invalid by that very activity. In other words, the production of films that would not stop insisting that, all appearances and tracking shots to the contrary, they weren’t really films. Fitting, perhaps, as both in these filmed works and the texts about them, the engagement with cinema lacks the partisan clarity of either sincere commitment to what cinema might do or cooler disdain of genuine non-participation.2 Instead, his works insistently pose themselves under an obscure and uncertain banner of what negates but does not destroy.

That absent destruction is not for lack of trying, or at least for lack of disavowal, invective, and abnegation. He will alternately declare his works to be “explicitly anti-art-film,” which he poses against “usual documentary practice” (his description of 1959’s Sur le passage de quelques personnes à travers une assez courte unité de temps), “against the cinema” (the title of the printed collection of his first three scripts), and, most pointedly, “anti-film,”boasting, with tongue not particularly in cheek, of 1961’s Critique of Separation in its opening moments as “one of the greatest anti-films of all time!” And yet, perhaps not in spite but because of this verve for the anti-, the turn “against the cinema” is no turning away, neither from fetish of the auteurish director nor the site of watching. It is a turning on, both in the sense of how a reel rotates on a projector’s spindle, and also in terms of the way in which a projector turns on its own designated process and bites the reel that feeds it. Put otherwise, this is an avowed rejection that cannot be separated from the materials of the cinema itself, its techniques, styles, audience memory, exhibition spaces, and, above all, its leftover footage, whether its final destination is the archive or the dustbin.3 Because his works may well not be films, even if, at the end of the day, they are made of nothing but film, and especially considering that they were drawn from sources that had no qualms about their identity. And his productions may be against the cinema but only as an against that is armed with lens and splicer, not match and gas can. Around the corner from the Watts supermarket, whose guttering flames furnished the Situationist International (SI) with an image of an eminently tangible “critique of urbanism,” the local cinematheque appears relatively unscathed, even if partially looted.

The question to ask of Debord’s engagement with cinema is simple enough: how does a declared “anti-film” relate both to film as such and to other films in particular? How does such an effort at negation—one that rarely produces its own film sequences from scratch but instead organizes recycled footage and still photos—actually engage with the materials it gathers toward abolishing itself, beyond whatever its textual supplement might claim to be doing? After all, the object of critique at hand is nothing internal to the history of cinema as a set of texts or stylistic tendencies. Rather, it resides instead in the connections one finds between concrete social experiences, such as cinema, and the material abstractions, such as the circulation of capital, from which they are inseparable. Ultimately, then, the convenient negation of the anti- in “anti-films” cannot take on that far messier zone of critique it gestures toward: a history of cinema, a history of capital, a history of the metropolis, and a moving, intersecting history of the contradictions of each.

We’ll reframe the argument, then, along the lines of three questions:

What historical situation was diagnosed by Debord, in both his writings and his films?

What cinematic terrain was mapped and engaged by those same works?

How—if at all—do those two zones of critique and analysis come together in the films? Does that point of contact give a plausible response, or pose further questions, to the injunction given at the end of Sur le passage, the one that forms a basic criteria to be posed to any cinema of critique: to “understand the totality of what’s been done, what’s left to do. And to not add other ruins to the old world of spectacles and memories”?

The drive of this essay is therefore to make better sense of Debord’s films through the -film half of “anti-film.” To do so is neither to discuss their merits as films nor to fantasize that they actually broke with “the cinema.”4 The first activity is one that bores me with any films; the second activity is a laughable misprision of the limits of negativity. Rather, my point is to argue that to see the films as just an extension of a non-cinematic practice—be that communist theory or more “practical forms” of social antagonism, like the aforementioned critique of a supermarket—would miss what was of actual relevance about them, especially with regards to those other practices.5

However, before returning to film and its specificities, I want to take an opposite route, one that runs the double danger of being both extra-cinematic and excessively abstract: a long passage through a particular process of capital and a category of Marxist analysis—accumulation—as it is taken up obliquely and imprecisely by the various threads of Lettrism and the SI, Debord’s solo projects especially included. As I have yet to find a convincing reconstruction of this scattered line of thinking in terms of the SI, a detailed move through it seems of real utility. Because only with the architecture of accumulation’s tense stasis in partial place can one start to make decent sense not just of Debord’s cinema but of cinema in general, of the twentieth century’s most extended elaboration of the relationship between the frozen and the moving. In other words, of one of capital’s most fundamental dynamics.

II. An Immense Accumulation of Accumulation

The central problem animating Debord’s thought, both political-economic and cultural, is the concept of accumulation, specifically insofar as it becomes a threat to capital as overaccumulation. It is there in the first sentence of Society of the Spectacle, thenotorious beginning that appears, at first glance, as an inconsequential and glib rephrasing of Marx: “the whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles.”6 No small portion of that book will be spent trying to say what might be meant by spectacles in the plural, although the term will be primarily taken up in its definite, singular, and universal form, the spectacle. Among the array of inconsistent definitions given, one is of prime relevance, the final thesis (§ 34) of the book’s first section: “The spectacle is capital at such a level of accumulation that it becomes image.”7

The murky stakes—and actual distance from the concept’s future as a banal claim about mass image culture—become clearer if we merge the two statements into a compound definition: the spectacle is an immense accumulation of capital at such a level of accumulation that it becomes image.8

Ascribing significance to this compounded thesis might seem like a faulty ascription of systematic language to a text that assuredly does not function that way. That misses the point, though, in part because reading this book against its grain is more generative than any imitative hagiography, in larger part because it gets at the historical specificity of the material grappled with by “spectacle,” that baggiest of concepts. That specificity is, simply, an immense accumulation of static accumulated capital, also known as overaccumulation.

What exactly is overaccumulation? Accumulation itself can designate the general growth in wealth, in money or commodity form, as a consequence of the circuits of capital—of an individual or a whole system (as in global capital accumulation). But that is simply a halted, visible form of the crux of accumulation: the temporary freezing of capital as either money or commodities before transforming again, one into the other, in the process of circulation. Because, for the system of capital, accumulation that does not’ re-enter circulation is a disaster: it becomes overaccumulation, as the reinvestment of a surplus-value that can no longer generate adequate returns; hence, capital is “hoarded.” Capital and labor alike go unused and yet do not disappear; they merely transform into wealth and life, each a hostile mass waiting for incorporation or destruction. More technically, necessary production becomes relative overproduction, and the necessary population of potential laborers becomes relative overpopulation of those already proletarianized yet unincorporable. As Marx frames it in Volume III of Capital:

Overproduction of capital never means anything other than overproduction of means of production—means of labour and means of subsistence—that can function as capital, i.e. can be applied to exploiting labour at a given level of exploitation; a given level, because a fall in the level of exploitation below a certain point produces disruption and stagnation in the capitalist production process, crisis, and the destruction of capital. It is no contradiction that this overproduction of capital is accompanied by a greater or smaller relative surplus population.9

Just like the rusting tangle of unused railways, the fallow soil of subsidized non-farming, and the unbought meat liquefying in the dumpster, that population become a feature of the present landscape. It is the static appearance of capital’s moving contradiction, a halted moment of its visibility become ornamental. In short, it is an image of capital, because capital can only be glimpsed in its moments of breakdown, when its relations blur into qualified figures: the silent factory, the burning slum, the hunger-striking prison, the barricaded highway, the flooded hospital, the riotous borough, the leaking reactor, the collapsing sweatshop, the looted mall, the teeming dump, the vacant field, the poisoned sea. Each is no longer functional and therefore slowed, hacked, and ground to the halting point of appearance, of becoming landscape and its accepted elements, always teetering on the edge of aesthetic recuperation into the merely natural. Drawn together, these accumulated images make up what gets called totality. And it is from this, from these blockades, shipwrecks, famines, devaluations, and slayings, that antagonistic thought tracks backwards in the direction of a harder sketch of capital’s quotidian obscurity; towards a model of its relentless flow, and a grasp of its cussed perpetuity.10

Overaccumulation has a contentious history in Marxist thought, especially as this history is bound to debates over the tendency of the rate of the profit to fall, itself the sword by which the “truth” of Marxist analysis has often been alleged to live or die. It rests at the heart of the “Downfall theory” (Zusammenbruchstheorie) debates involving Henryk Grossman, Rosa Luxemburg, and Karl Korsch’s11 critique of both, followed later by Paul Mattick’s critique of Anton Pannekoek’s alleged misreading of Grossman.12 Unsurprisingly, given the tenor of his work and his disdain for citation, Debord doesn’t engage with these debates, neither substantively nor otherwise. However, György Lukács, the Marxist with whom Debord deals most explicitly, is deeply enmeshed in the work. As Giacomo Marramao writes, “it is no accident that it is precisely in Lukács’ History and class consciousness that one finds the philosophical equivalent of Grossmann’s great attempt at a critical-revolutionary re-appropriation of Marxian categories.”13

Instead of ill-fated speculation over what Debord might have read, we should ask: what is the relevant relationship of his thought to overaccumulation? The development of the concept in Marx’s own work, in the period between 1857 and 1859, appearing respectively in the Grundrisse and A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, offers a way into this.14 The concern in both of Marx’s iterations is with the third function of money (accumulation), beyond the first two (money as medium and money as measure). This third function is occasioned by the prospect of crises, where a discrepancy is said to arise between production and its realization, or between the value of commodities and the price they fetch in sale.

In the 1857 model that derives from the monetary circuit (M-C-M, buying commodities in order to sell them), accumulation is seen as the process through which surplus money “steps outside of circulation” in a “piling up” (Anhaufen), rather than being plowed back into circulation. Of course, it can become capital again, if reentered into circulation, but at the moment of “stepping outside,” it is “money as money,” a means made end in itself. In this version, the problem of the gap between money needed for circulation and money that exists is “solved” by the casting of money out of accumulation and back onto market. As Marx puts it, “Its independence is not the end of all relatedness to circulation, but rather a negative relation to it.”15

By 1859, however, in A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx’s theory of accumulation had shifted substantially in both conception and emphasis, for the primary reason that it was no longer explained by the monetary circuit but by the commodity circuit (C-M-C). Of particular relevance here is the real emergence of the idea of hoarding in Marx’s work: not the “hoarding principle… necessary as one moment of exchange resting on money circulation,”16 i.e. a piling up of money outside of circulation that is able to be remobilized; but instead hoarding as the creation and piling up of more use-values—including the use-value of money, as medium of exchange—than can be consumed. Money coming to “be money” therefore occurs when it cannot reenter circulation. When it becomes leftover, its use-value is negated even though it still remains. Money shapes the world through its negative presence (quantity withdrawn from circulation) and freezes into a non-productive (i.e. non-surplus value generating) hoard.

The key point is that overaccumulation, as a moment of crisis, is not just overaccumulation of money. It includes and produces other use-values to be piled up to the point of hostile inutility—all of those waste products of circulation, labor, production, and consumption. In short, accumulation is a standing side-by-side of devalued surpluses. On one side, what was pulled from circulation in the past: money, unused means of production, unpurchased commodities. On the other, what will remain barred from circulation in the present: potential laborers. And in a situation wherein something has to give, even a short history of the last centuries reveals that the bodies of the poor—along with cities, farms, and access to subsistence—have proved consistently more dispensable for capital, be it through downturn, famine, or wars civil and world.

To pose a definition, then, in the terms of Debord’s work: spectacle means the relation of accumulation to itself,17 insofar as it simultaneously instantiates, threatens—yet also withholds—a potentially general breakdown of circulation.18

More crucially, it shapes the concept of separation itself, as central a mechanism of Debord’s thinking as it was for other heterodox communist thinkers throughout the twentieth century. Capital depends on separation, because it can only become a value-producing relation—a relation itself being a binding mechanism of the separated, “brought back” (referre) to each other under the sign of unity—on the condition of having driven and maintained a wedge of separation that splits in terms of class, gender, race, time (labor and “free”), terrain (city and country), and on from there.

“Organic” as such separations may come to seem, they are needed only insofar as separations impel, rather than impede, the circulation of capital. And impel they do, against much-fêted narratives of the interpenetration of previously discrete zones of life. For instance, capital will always require the structure of gender division so as to naturalize unwaged reproductive work into the category of the housewife (the subject who works on the reproduction of subjects other than herself, and despite the fact that this work is always unpaid). It does so even as the social coherence of the nuclear family unit—itself a brief historical emergence morally fixed as endpoint of natural progression—goes to pot in much of the global north.

Separation is functional, though not because it keeps antagonists apart. Rather, separation works because it produces the conditions for its apparent violation. Separation draws, in one and the same stroke, both a canyon and its bridge, the latter to be crossed as the necessary exceptions; or, capital’s four major unremunerated extractions: the wage, the colony, the family, and the city. The wage provides the image of total quantification and free sale that makes possible surplus-value, the portion of thieved time that alone justifies the capitalist’s expenditure on the full “fairly paid” day. National boundaries exist in order to enable their breach in colonial violence, “humanitarian intervention,” and resource theft. The family complex serves to produce the base condition of value and abstract labor—proletarianized labor-power—in a temporal zone delimited from direct market mediation and the real subsumption of labor.19 And the ideology of city and country erects the screen behind which urban plans generate rent differentials to enable land speculation, while sprawl—i.e. the logic of the metropolis as visible, infrastructural, and extensive—evacuates any significant difference between the designated sites. These four exceptions are the prime laws by which the capital relation reaffirms itself, and so it is that separation only becomes a problem when it cannot adequately guarantee that relation’s movement, when it becomes static and comes into visibility as overaccumulation and its all its shades of the devalued, scrapped, and junked.

Spectacle, then, designates both this becoming visible and the temporary triumph over stasis. Having split what was never a coherent unity to start,20 separation becomes the grounding condition for circulation. However, this crowded separation threatens itself by barring exit from its total logic: the more that piles up, the more there is of it that cannot truly touch or integrate. So it stands next to itself “a pseudo-world apart,” only and ever to be bridged tautologically in a self-reinforcing cycle, while the excess of that cycle spills out and out.

However, to say that spectacle designates not just the threat of long-term stasis but also separation’s productive force is to recognize how the term concerns not a general condition of capitalism but a distinct historical period: the three decades following the second World War and its discernible trendlines. Unlike earlier twentieth-century thinkers more rigorously concerned with overaccumulation and collapse theory, Debord was living, writing, and filming during the golden years of global capital and its extremely “healthy” reinvestment of surplus-value into new production, which was triply fed by post-war Marshall Plan-backed reconstruction efforts, tremendous internal migrations to furnish industrializing sectors with swelling ranks of mass workers, and new consumer markets that thickened the relation of workers and capital to include that of consumers and capital in an unprecedented way. In short, this was the period in the twentieth century when solutions to overaccumulation proudly bared themselves at their most advanced and robust.

It is therefore little surprise that the task of Debord’s analysis, far as it was from actual economic analysis, was to make sense of possible antagonism in this period of scarcity’s alleged defeat, a time when, for increasing portions of the global north, the relevant “poverty” was that of experience, not available calories as such. This is the dilemma tackled by thesis 115 in Society of the Spectacle, which is worth quoting at length:

New signs of negation are proliferating in the most economically advanced countries. Although these signs are misunderstood and falsified by the spectacle, they are sufficient proof that a new period has begun. We have already seen the failure of the first proletarian assault against capitalism; now we are witnessing the failure of capitalist abundance. On one hand, anti-union struggles of Western workers are being repressed first of all by the unions; on the other, rebellious youth are raising new protests, protests which are still vague and confused but which clearly imply a rejection of art, of everyday life, and of the old specialized politics. These are two sides of a new spontaneous struggle that is at first taking on a criminal appearance. They foreshadow a second proletarian assault against class society. As the lost children of this as yet immobile army reappear on this battleground—a battleground which has changed and yet remains the same—they are following a new “General Ludd” who, this time, urges them to attack the machinery of permitted consumption.21

On these grounds, the relevant critique—both in essays and in the streets—will be posed in the negative: not in terms of overaccumulation itself (as the negation of circulation, appearing as a static image of capital) but in a two-fold negation that arises from a system trying, and partially failing, to manage fully the contradictions of the avoidance of stasis. “The failure of capitalist abundance” exacerbates both that generalized poverty of experience and a continued incapacity to adequately propitiate working class antagonism, in spite of a then historically unprecedented access to goods, food, and services.22 At the same time, “new signs of negation” start to show themselves, not to mourn or return to traces of lost experience but to turn against previously active structures of antagonism, such as unions and party, and the process and circuits of massified consumption. The mode that this refusal will take, in theory at least, is sabotage, now unbound from designated sites of labor and let loose into the general sphere of reproduction.

Here lies the real tension internal to Debord’s thought. It is an analytical framework centered on the negative potential of separation (as accumulation gone too far), yet it is based on and written in decades when that separation seemed under managed and, according to Mandel, “neocapitalist” control able to neutralize the toxic energies of its side-effects. Those brief foreshadowings about a “second proletarian assault” can hardly ward off the claustrophobia sketched at more length, especially given the wholly vague quality of the proposals on revolutionary organization via the workers’ council that conclude the long section on “The Proletariat as Subject and Representation.”

The thought as a whole therefore arrives under the sign of a revolutionary pessimism, doubtful about whether or not these peculiar “material conditions” still have the alleged capacity “to blow this foundation sky-high.”23 However, it will not abandon the potential forces stored within this bound separation, pursuing it instead across registers and away from the relation of capital to a relation to history. The crux of that second relation is the hanging question: how do materials negated in the past persist into and constitute a present “immobilized by non-history”?24

To borrow a distinction I’ve made elsewhere, this concerns the gap between destruction and negation, destruction indicating the active labor of dismantling an entity or form, negation the undoing of bonds of historical coherence that support and reproduce those entities or forms.25 These bonds include a full range of elements: naturalized conceptions of exchange; cops; racial demonization; consumer credit; architectural style; foisting of vacuums and amphetamine on housewives; and, above all, the prescriptive overlay of a descriptive category, such as “the working class,” onto the persons it describes.

Undoing these bonds (the process of negation) is an act at once conceptual and material.

Consider an example from the center of the long Italian 1970s: the critique of unwaged domestic labor pushed by communist feminists. This required both a conceptual negation (an attack on a certain interpretation of capital, which called into doubt capital’s restrictive focus on the wage) and a material threat to the unspoken support mechanisms (housework for free, as well as affective care, “motherly love,” and sustaining domestic violence). The second threat is critical because such mechanisms allow the wage to be imagined by a dominant Marxist interpretation as the lynchpin of struggles against capital and by workers themselves, as a “living wage” adequate to support the family as a unit. However, such total processes of negation are not acts of autonomous will, projects of autonomy aside. They took their cue from crises (housing, 130% price increase in consumer goods between 1910 and 1977, oversaturation of industrial sector, etc.) and the long-scale breakdowns of social and communal forms. For instance, the collapse of an agrarian structure of everyday life and work for the majority of Italians (and Europeans) across the 20th century made the reproduction of potential workers less a concrete material benefit for the family (in terms of sharing farming duties with parents and eventually providing for them in older age) than it once had been, thereby negating the coherent tie between the reproduction of labor-power as such, to be employed on farm or factory, and its benefit for a specific family.

It was on these grounds that bearing and raising children started to appear unmistakably what it long had been: working for free to furnish capital with the corporally individual and legally free—and therefore disposable and exploitable—units of labor-power it needed, to be reduced to carne di cannone (cannon fodder) when too plentiful or left to starve and hustle en masse in baracche (shanties) when the market got itself glutted. And so, aided by the corrosive critical turn of those writings, the care for loved ones showed itself as the hidden grunt work underlying the postwar economic “miracle,” all those ex machina muscles and cranesstraining to make a monstrously bloated deus appear on the world historical stage as if under its own steam.

This kind of negation is both an inherent quality of modernization (the destruction of the bonds of experience, communal forms, and subject positions) and the more specific terrain of a uneven line of anti-state, radical, and left-communist political thought that lays its focus on such shifts. In this conception, the roots of which lie in interwar council communism, the subsequent post-war French and Italian extension/critique of it, and productive interference with anarchist traditions, the revolutionary process is not envisioned as a building-up of working class power to the point of seizing state and industry (which itself has been “accelerated” into full productive capacity). Instead, the process of communism unbinds the capital relation from all its secondary processes and structures, such as the raising of children or the rezoning of the city, without which it cannot function. It enacts this unbinding not in theory alone but through a hostile and highly practical realignment of “the secondary” against itself, as the mother refuses mothering and the barricade uses the city to block the city: sabotage, in other words. From this follow two further possibilities: salvage (the hijacking and counter-assemblage of those rare elements of apparatuses not wholly determined by the conditions of surplus-value) or wreckage (knowing what can only be of use when melted down to its component materials).

However, as this follows from a condition—social decomposition, general hostility, and interruption of circulation—already determined beyond the will of the negators, the situation is antagonistically charged but not politically coherent. And as such a process of negation leaves the negated intact and in place, merely without its guaranteed reproduction by other structures and relations, if such a situation is not seized and exacerbated by a mass of those antagonistic to the social order, the negated will not “wither away.”

It is this dynamic—that tension between destruction and negation, especially how the process of the latter does not guarantee the former—that I see at the center of the thought gathered, articulated, and occasionally fended off by the SI, as well as the aspect most worth excavating and think through now. The gambit of the SI was to begin with a condition obvious enough to any radical history, that the extension into either salvage or wreckage is neither neither guaranteed nor frequent. But the key move from there was to grasps how the historical sequence they were writing and thinking in put the negated back into circulation more efficiently and completely than ever before, as capital no longer denies or wards off of the prospect of overaccumulation. Instead, that prospect is openly acknowledged and incorporated into the total reproduction of capital, a cynical shrug of self-display and plowing ahead that undergirded the boom years’ Stimmungen, its haze and circuits of moods, affective disposition, and cultural complicity.

Perhaps more precisely than spectacle, the situation as a whole—a particularly political judgment on the failure of enacted destruction and an aesthetic interpretation of the unfulfilled decay of forms—is grasped by the SI as the historically specific period of generalized “decomposition.” Unlike overaccumulation, decomposition is a central and explicitly articulated concept in the wider domain of the SI’s thought. Like many of the ideas whose source they would rather not acknowledge, it comes from Isidore Isou, their once comrade-in-Lettrist-arms later disowned. Isou argued that, in McKenzie Wark’s paraphrase:

All forms—aesthetic and social—move from a stage of amplification to one of decomposition. In the amplification stage, a form grows to incorporate whole aspects of existence. The amplified form shapes life and makes it meaningful. During the period of decomposition, forms turn on themselves and become self-referential. Forms fall from grace and from history. As the form decomposes, so does the life to which it once gave shape.26

This model remains wholly intact Situationist writing even after the break with Isou.27 (If anything, what get unfortunately left behind are the key dynamic of Isou’s amplification as a process of mutual subsumption: social, aesthetic, and political forms incorporate categories, activities, and other forms in ways that transform the latter into confirmations and alterations of the forms that envelop them.)28

The move from Isou’s theory of decomposition to that of the SI, if the latter can be described as roughly unified, occurs in two ways:as generalization, a process centered on the trajectory of specific forms, such as abstract labor or the mass audience, to a total cultural and social logic; and also as repetition, adding a third phase where forms may well have fallen “from grace and history” but do not disappear from the present situation. As the “definition” of decomposition provided by the SI in 1958 puts it, decomposition is the

process in which traditional cultural forms have destroyed themselves as a result of the emergence of superior means of controlling nature that make possible and necessary superior cultural constructions. We can distinguish between the active phase of the decomposition and effective demolition of the old superstructures—which came to an end around 1930—and a phase of repetition that has prevailed since that time. The delay in the transition from decomposition to new constructions is linked to the delay in the revolutionary liquidation of capitalism.29

In other words, without destruction/“revolutionary liquidation,” no new construction is possible because any construction could only confirm what already is. So the negated— lacking coherence and historical adequacy but not force—goes nowhere. It is raised through repetition into a style, an assemblage of operations across different instances that become newly and retroactively coherent through this repetition.

The most visible site of, and the source of the SI’s thinking on this is the arts, specifically the autophagic fate of the historical avant-garde:

the solutions put forward by reactionary trends ultimately boil down to three attitudes: a continuation of forms produced by the crisis of dadaism and surrealism (which is merely the developed cultural expression of a state of mind that spontaneously arises everywhere when past ways of life, the reasons for living accepted until then, collapse), a settling into the mental ruins, and finally the long look back.30

This “settling into the mental ruins,” followed by the melancholic contemplation of its trajectory, pursues an end-game without end in sight. Unable to generate further motion on the basis of its own energies, it produces instead a “general cultural picture, wherein we see a state of decomposition […]that has arrived at its final historical stage.”31

Of course, things go from worse to worst. Because it lacked the prospect of novelty (a newness that, for the SI, would have entailed the further dissolution of the categories both within art and of art itself), the negativity of the avant-garde can only become fêted and massified.

At this moment, decomposition shows nothing more than a slow radicalization of moderate innovators toward positions where outcast extremists had already found themselves eight or ten years ago. But far from drawing a lesson from those fruitless experiments, the “respectable” innovators further dilute their importance.32

However, barely-veiled swipes at Godard notwithstanding, this state of recycled decrepitude isn’t purely damning, provided one could learn to ride the negative tiger: “The positive significance of the modern decomposition and destruction of all art is that the language of communication has been lost.”33 Anticipating the analyses of both Massimo Cacciari and Giorgio Agamben, the SI’s conceptualization of the destruction of experience—the collapse of the conditions of communication, to employ Walter Benjamin’s framing—raises a discrete possibility that lies in the new use of those repeated materials through montage, bypassing the absent “language of communication” that had situated them in prior cultural traditions and social formations. This is the particular grounding of détournement.

[Détournement] arises and grows increasingly stronger in the historical period of the decomposition of artistic expression. But at the same time, the attempts to reuse the “detournable bloc” as material for other ensembles express the search for a vaster construction, a new genre of creation at a higher level.34

With this practice, an answer to, and further articulation of, historical negation poses itself: not by new construction as such but as a passage through the echo chamber of the negative toward a “new genre of creation,” which incorporates the materials freed up by decomposition into “other ensembles.”

However, this will not enable the construction of a common language merely transposed to a minor key because

a common language can no longer take the form of the unilateral conclusions that characterized the art of historical societies—belated portrayals of someone else’s dialogue-less life which accepted this lack as inevitable—but must now be found in a praxis that unifies direct activity with its own appropriate language.35

In terms of concrete activities, this “praxis” not only involves the celebrated construction of situations, dérives, and the like, but also a continued activity of working on and with negated materials. However, because this activity requires “its own appropriate language” and also access to the common language of experience that has been severed, this can only emerge on the basis of those materials themselves. One will have to learn to take a cue or two from that maligned and disarmingly active waste-heap. This condition in particular bears most directly on Debord’s film works: above all, their decision to be composed of pieces pulled from other films. The question this raises and that this essay pursues, is of the degree that these works finds a language within those scraps and their montaged junctions, rather than a pre-existent one merely laid over them.

What, finally, are the consequences of this decomposition? First, it bleeds over from a discrete sphere of cultural consumption into zones of circulation as such, especially the city, because “the technical organization of consumption is only the most visible aspect of the general process of decomposition that has brought the city to the point of consuming itself.”36 Second, it generates a crisis of a coherence between judgment and its historical situation, meaning that it is not only the construction of the new comes that comes into corrosive doubt. So does critique itself:

The crisis of modern culture has led to total ideological decomposition. Nothing new can be built on these ruins. Critical thought itself becomes impossible as each judgment clashes with others and each individual invokes fragments of outmoded systems or follows merely personal inclinations.37

This situation, one rendered grossly liberal by Gianni Vattimo, prepares the ground for a general nihilism, not because of the total extension of the negative but because even negation can no longer find a grounding and merely slips instead between “fragments of outmoded systems.”38

Third and finally, this erosion of critique generates a major collapse of the sense of being historical—especially of being vanguard, galloping at the front lines of social transformation—into mere confirmation of the present. According to one of the bleakest lines penned by Debord: “It is no big deal to be up to date: one is only more or less part of the decomposition.”39 And as decomposition indicates the separation of historical presence from present materials, one has no choice but to be anti-historical. The only question is whether that takes place beneath a false flag of imagined rebellion (knowing how to “go too far” just far enough) or through truly taking on that collapse as given yet incomplete.

However, what is the particular mechanism undergirding this motion of decomposition in its period of repetition? Still drawing from Isou’s schema, it is better understood as a coming apart that does not threaten but reassures what Debord calls the “coherence of the separate.”40 This phrase appears in his attack on Leninism:

As the coherence of the separate, the revolutionary ideology of which Leninism was the highest voluntaristic expression governed the management of a reality that was resistant to it; with Stalinism, this ideology rediscovered its own incoherent essence. At that point, ideology was no longer a weapon; it had become an end in itself. But a lie that can no longer be challenged becomes insane.41

If one can temporarily ignore the simplistic character of Debord’s take on Leninism and the party, the underlying mechanism identified is crucial. First, something is separated from its referent. The revolutionary party and the proletariat refer to each other but are no longer unified in a common process of social war. Second, the party remains operative and coherent in this separation, for reasons that can only and ever be understood as particular to a historical conjuncture. An image of antagonistic process undone from its purpose, it becomes an end in itself: it becomes ideology. Third, the party-as-ideology still “governs the management” of a reality resistant to it, articulating the concerns and drives of a present situation in terms of a past arrangement when it was, in fact, articulated by the party. Finally, and crucially, the party—as the apparatus of “revolutionary ideology”—rediscovers its historical presence in a stable incoherence, having developed new support mechanisms. Fully decoupled from the processes that brought it about, the party can no longer be challenged. In terms of revolutionary practice, this is, obviously, a wholesale disaster. In terms of capitalism, it is one of the fundamental operations through which seemingly outmoded forms prove functionally dominant toward new ends.

This process just described at length constitutes the historical mechanism I would argue is the most significant contribution of the SI to thinking history. I’ll term this simply the pseudo. Unlike decomposition, the use of pseudo- is never theorized in the SI’s texts and appears instead as a recurrent prefix. It is one, we should note, that also plays a crucial role in the texts of Adorno (“pseudo-individuality,” “pseudo-activity”)42 and especially Kracauer (“pseudo-luster,” “pseudo-coherence,” “pseudo-middle,” “pseudo-reality,” “pseudo-life”). But in Debord’s writing, it becomes a rhetorical obsession, appearing no less than forty-five times in Society of the Spectacle and furnishing one of its central concepts (“pseudo-cyclical time”).

The form of the pseudo can be understood alongside Debord’s chiasmatic description of a “visible negation of life; a negation of life that has become visible.”43 The echo of my earlier analysis of accumulation should be clear enough. However, this echo should not be taken as an act of negation that makes itself visible, a noticeable subtraction or destruction, a famine or riot in the present. The pseudo is the present condition of a past negation that did not decay but became image, a negated term that remains in circulation. It is this obstinate persistence that forms the second half of the general process of separation, the answer accumulation gives to itself, enabling the outmoded to circulate as if living and curse the living as if undead.

Such is Debord’s account of the working class in the moment of the Bolshevik revolution, “the moment when an image of the working class arose in radical opposition to the working class itself.”44 The point of this is, like the analysis of Leninism cited above, is to identify both a splitting (proletarian hatred and a bureaucratic articulation of proletarian hatred) and a freezing. The “image of the working class,” which crucially contains both sides of that split, continues to assert itself as the correct elaboration of proletarian hatred, long after its form can no longer accurately describe and extend that antagonism across drastic shifts in historical terrain.

Another concrete example from Society of the Spectacle helps clarify this process: “As urbanism destroys the cities, it recreates a pseudocountryside devoid both of the natural relations of the traditional countryside and of the direct (and directly challenged) social relations of the historical city.”45 The fact that urbanism has concrete proponents and flesh-and-blood designers changes nothing, given that it makes little sense to imagine some diabolical planner choosing to impose the pseudo.46 Rather, the present city (the accumulated and lived outgrowth of the historical city that had challenged and “negated” the social content of the countryside) is destroyed by the return of what was incompletely negated—not just the countryside, but the binary of the city and the countryside—and therefore is capable of reimposing its rule. 47 Such a destruction is possible because the pseudo-countryside lacks both sides of the historical contact that would allow substantive engagement with and negation of it. It lacks the “natural relations of the old countryside,” and it lacks the social relations that the historical city had challenged. The pseudo-landscape becomes auto-referential, one more part of capital’s “enormous positivity.”

Yet to be clear, what comes back, in an entirely non-spectral fashion, is neither historical backsliding in the direction of “precapitalist” relations, nor a new configuration of the countryside that responds in innovative ways to the impasses of the urban, much as one finds in Soviet disurbanist theory. It also is not equivalent to the oft-proposed cultural logic of the postmodern in which “the countryside” would belong to a defanged regime of relatively neutral signs emptied of their historicity. No, the pseudo is the imposition of negated historical material, lacking not its particular qualities but the social relations and texturesit both emerged from and gave shape to—including those of the city it comes to dominate under the labor of urbanism. In its most recent iteration, this manifests itself in thousands of heirloom chickens kept lovingly on Brooklyn rooftops, regarded quizzically by trash-fed pigeons.

What cuts against this? After all, the negation of the pseudo can’t itself be a negation, as the structure of the pseudo incorporates its own negation as a principle of its preservation. What then? The operation, as mentioned before, is that of sabotage, only explicitly present in the writings of Debord and others of that circle at rare moments.48 But despite providing the ground for détournement as outlined above, a wider inquiry into sabotage makes clear both the range and limits of this cultural technique.

Simply put, sabotage indicates the use of means designed for a specific end, and which only exist as such, against that end. For example, when one “over-salts” the soup: the combined means of salt and cook, which are only present in the restaurant to work on edible materials to increase the value of that food, ruin the edibility, and therefore profitability, of the food itself.49 (Simply torching the restaurant where one works is not sabotage, cathartic as it surely would be.)

Sabotage is therefore the verso of the pseudo, the push toward decomposition posed against its principle of preservation. The pseudo preserves social order by taking up an entire image, such as “the countryside” or “the working class,” as an end toward which prior means had been mobilized. It transforms the image into a means against that end (pseudo-life against life) and toward a different end: the maintenance of the capital relation as such. Sabotage refuses this transposition of means into an end, insisting instead on the particular qualities of things as in excess of the ends they were designed for. It does not mobilize images but rather entails a continual process of negation. Sabotage takes a unified process—the circulation of capital in general—which is opened up by decomposition. Sabotage thus turns its elements against themselves, thereby both lessening the coherence and dynamism of a form—insofar as, following Isou’s model, it now incorporates less of the world—and frees up those elements for some other possible use. And so, sabotage is not the pseudo’s “visible negation of life” but the coming into visibility of negation’s means: techniques decoupled from life or purpose, unfrozen potentials and hostilities, and materials for whatever process of social war.

In short, if sabotage is to mean anything, both in the industrial and cultural sense, it will lie in a dual assertion. First, the means—the materials of a process—contain more than a simple expression of their end. Second, the lead can only be given by the means themselves and that their peculiar texture allows for an attack on those ends from within the process of its reproduction. The relevant question, then, that this poses is that of the relation between means and ends, of their potential identity and difference in a period when the logic of the pseudo has transformed that very relation.

As my exposition should already make clear, however, while the critical framework of decomposition and détournement provide materials to approach this question, it cannot respond in a compelling way. Instead, it answers the first assertion of “means as more than means to an end” by drawing an uncritical line between humans and other elements of capital, fetishizing the creative, albeit restricted, vitality of they who labor or play. The result is that this theory has to posit that, although humans are historically determined (i.e. subjects of labor-power) and produced by primarily unwaged human labor (i.e. reproductive labor), these keepers of that mysterious “life” are capable of breaking with determination while products of human labor, including highly complex ones such as films, are considered nearly identical to the system of separation that conditions them.

In terms of the second assertion—sabotage as driven by the peculiarity of those materials—the theory will show itself too little interested in the textures of what it also derides, asserting, in addition to that unquenchable spark of life, an incoherent divide between “real life” and “pseudo-life,” conveniently forgetting that going to the cinema, for instance, is entirely part of the flow of real life and quotidian experience.

However, my ultimate interest is not in the correctness of this thought but, on one hand, the historically particular situation it confronts, and, on the other, the operations within Debord’s films themselves that gesture away from the theory and toward a different kind of negative energy and elaborated contradictions, one buried within the history of film style itself. Because it is in the films themselves, separate from the words their narrators intone about the cinema but not separate from the fact of that voice, which an inquiry into and through a new wasteland of accumulation will be posed with more rigor than elsewhere in his thought.

III. Que faudrait-il prouver par des images?

The specificity of film, as a means, is movement. Even when an image does not move, as many do not in Debord’s films, it is not a still image per se but a negation of the moving image: a set of constant frames, each of which could give different information but do not. Yet, these moving images are themselves a moving negation, emerging as they do from an enormous accumulation of halted frames accelerated to the point that they either regain a semblance of motion (reanimation) or take on a movement they lacked to start (animation). From the start, then, the moving image of film is what I will call from here on a pseudo-image. It is a negation (i.e. the halting of motion) not destroyed but accumulated to such a degree that it impels another negation of motion: the fact that movie-going requires viewers who come to a specific site and pay to stay there, neither to witness a singular performance/work of art nor to own the means of transmission (TV and radio). They come to rent time in that location. There, they watch the exhibition of a commodity that exists in multiple, one that specifically depicts an imitation of “natural” movement. The qualification of “natural” that emerges only retroactively with the development of the cinema is therefore not recognized as lost until the period of mechanical reanimation. For a thought like Debord’s, which depends on a persistent homology of micro and macro, this can only be considered an affirmation of pseudo-life, straight from the technical apparatus through the logic of consumption to the entire historical situation of that mass of scrap made to dance. Cinema is the a-subjective form of this, only able to “uselessly consume itself in amassing the images time brings”; a technical passivity that mirrors its audience’s experience.50 Fittingly, then, Debord claims that the “cinematic spectacle” is “one of the forms of pseudo-communication (developed, in lieu of other possibilities, by the present class technology.”51

However, as we have seen, the spectacle “cannot be understood as an abuse of a mode of vision, as a product of the techniques of mass diffusion of images.” So, too, the image is not equivalent to visual images.52 Instead, we confront a problem of the historical mode of the image as the capture of a fleeting present into historical fixity and one thereby capable of becoming outmoded yet presently operative: of becoming pseudo.

This pseudo-image is the basic unit of spectacle, from molecule to system, articulated variously as an effect of accumulation, the basis of ideology,53 and the total logic of a period made manifest: “a Weltanschauung which has become effective, materially translated[…] a world vision which has become objectified.”54 The image is not constructed but is a consequence of the negative, an operation of unbinding. One does not make images. One encounters them, dodges them, works on them. The question follows: what is the relation between the pseudo-images of cinema and the images of capital? Can such images be sabotaged? And if they cannot, what else would make it worth attacking the cinema from within?

In other words, why make films, “anti-” or otherwise?

Given Debord’s association of the image with more literal forms of spectatorial passivity and historical stasis, it is no surprise that the cinematic image is read not as source of resistance but as curse. The fundamental question posed, however, is that of proof: to what degree are images necessary, as opposed to the idea of an image as contingent and self-evident; as opposed to a notion of the image as that which requires the supplement of narration or exegesis? In other words, if severed from their context, do images carry within them anything more than a busted and baleful remnant of their lost motion?

In certain lines of aesthetic and film theory, this is taken up as the problem of “monstration” (self-showing/self-evidencing). André Gaudreault, for instance, in his interpretation of forms of vision in early cinema, distinguishes between images that narrate (through temporal editing) and images that “monstrate,” or show.55 The latter requires a supplement, whether that be an external narrator (as was the case in certain national cinemas, like France, Japan, and Korea), the use of inter-titles, or—as was to become the case everywhere—the gradual partitioning off of monstrative cinema into specific generic categories (experimental film and, in the case of narratively-secured individual sequences, horror, musical, and action). Jean-Luc Nancy, on the other hand, wants to assert this monstration as a property of all images and argues that they bear a monstrous “pre-sense” that the human animal nevertheless processes towards a narrative end.56

For Debord, however, the answer is different and three-fold, and given against itself in the narration of his last film, In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni (1978).57

First, the image itself is decried as giving proof to lies: “Existing images only prove existing lies.” However, the particular phrasing is important: existing images, which refers to both actually pre-existing film (the found materials that make up most of his films) and to newly produced film in accordance with “images” of the world order. Moreover, such images themselves are routinely disdained as being valueless or trash: “I am simply stating a few truths over a background of images that are all trivial or false. This film disdains the image-scraps of which it is composed.” Second, it will be asserted that truth does not need to be, or even can be, proven by images. The narrator sneers, “there are still some cretins […] who claim that it is ‘dogmatic’ to state some truth in a film unless it is also proved by images.” More plainly: “What needs to be proven by images?” Third, both truth and proof are operative and necessary categories, despite the fact that images fail in the face of them. But how does one speak truth, how does one prove? As the narration states “dogmatically” (its own self-description): “Nothing is ever proved except by the real movement that dissolves existing conditions—that is, the existing production relations and the forms of false consciousness that have developed on the basis of those relations.”58

In short, proof will come through the ruination of the existing in the movement of negation. This is the exact opposite of the image, which can only prove the justifications of the existing truths as tautological confirmations of “existing production relations.” To state truths, “dogmatic” or otherwise, one must speak in negation’s voice while simultaneously trying to inflect away from a self-same nihilism of decomposition, one that merely enables the recurrent dissolution of the singular that forms the crux of exchange.

IV. Alleged Inadequacy

Still, though, after the black and white screens of Hurlements en faveur de Sade (1952), Debord’s films will be composed of images, images that have exited their circulation (as newsreels, newspapers, or feature films) and hence have ceased to participate in the circulation of capital directly. It is on this ground that his cinema is directly put into contact with the problems of circulation and accumulation raised before: regardless of what the films will do with this material, the substructure of their composition is a contact with a real and ongoing process through which commodities (reels of film) transfer their value over time, are pulled from market, and yet are not destroyed. Practices of recycled cinema are in a prime position to process the circulation of capital more generally because they begin quite literally with the scraps of a specific industry, the cinema, that is itself marked more than almost any of the 20th century by a long meditation on how to profit from the repeated circulation of fixed capital (the “movie,” physically manifested in the reels) without it entirely and irrevocably transforming back into money capital. The question is therefore not if Debord’s films work on this rubbish but how. What do they do with their specific grounding condition, the aftermath and resilience of elements in circulation? What is the actual specificity of these films, their mode and method?

The first sequence after the credits of Sur le passage, the film that sets the groove to be followed by the next four films over the next nineteen years, provides the exemplar.59 It opens with a stable shot of the facade of a building in Paris (over which is written “PARIS 1952” on the surface of the film itself). This is a moving image, in three senses: the static motion of animated stoppage in general, due to the technology of cinema; the movement of people on the sidewalk; and, after a two-second pause, the motion of the camera itself, as it pans right across the building over the course of fifteen seconds before coming to rest again. Next, three shots, broken by cuts: the outside of a building, the entrance to a metro, and a view onto the upper stories of apartment buildings (coupled with another pan to the right). During this sequence, a voice, one of three “somewhat apathetic and tired-sounding voices”,60 intones, describing and qualifying the neighborhood being explored at that moment.

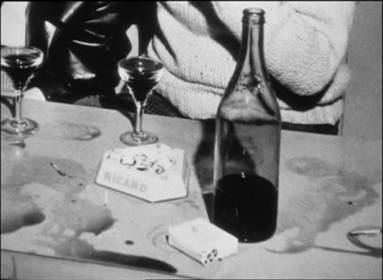

Fig. 1

The film then cuts to a proper pseudo-image raised to further visibility and contradiction: a filmed photograph of four figures seated around a table, drinking, smoking, leaning against each other. [Fig. 1] String music (Handel) begins. The camera holds steady before the photo, zooms in to a detail (wine spilled on the table) before panning down and then tracking up over the surface of the image.61 [Fig. 2]

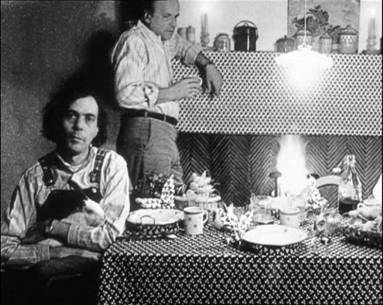

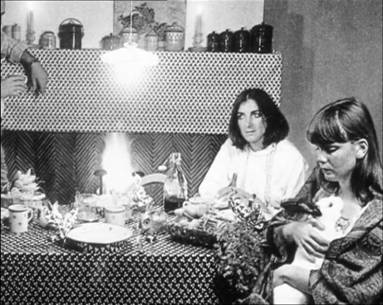

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

This sequence of camera movements is followed by a cut, leaping to the right side of the image, to hold on a face. The sequence is followed by further cuts, all of which are framed onto the faces of the figures, jumping closer and closer in, picking out details (a clutched cigarette, eyes, a face before panning down to wine) [Fig. 3], with the frame wavering slightly (the combined agitation of the camera’s handheld movement and the projector’s rattle). The camera then zooms out from a close-up of the spilled wine [Fig. 4] and pans left to recreate the original framing of the entire photo. In an abrupt cut, an answer is provided by a semi-reverse shot: not onto the photographer herself, but onto a position on the other side of the table, framing close on the woman whose back was to the audience/camera. Lastly, another pseudo-image, one unhalted even once further: a filmed still from a film, of Isidore Isou himself as “Daniel” in the foundational Lettrist film Traité de bave et d’éternité (1951).62 The voice, meanwhile, has not stopped: it becomes a different one—Debord himself, “more sad and subdued”—before switching back to the former, to the voice that both describes and ignores what is shown.

In these two minutes, wherein the most famous visual aspects of Debord’s films—the montage of borrowed newsreel footage, snippets from mainstream film, and images from advertisements—are pointedly missing, we have a set of operations that makes up what I argue is the actual specificity of that cinema, which passes through the history of film style itself, bringing into this negatively filmed space a set of historically distinct orders and modes of vision.

What operations? First, at the very outset, the camera stays in a fixed position while motion is staged or occurs in front of it—a technique that characterizes the tableau-framing of most early cinema until around the end of the First World War. In many films toward the end of this period, directors such as Louis Feuillade (Les Vampires) supplemented the fixed camera with staging-in-depth. However, across the teens, the majority of films, with notable exceptions such as Giovanni Pastrone’s 1914 Cabiria (1914), one does not find an actively mobile gaze. Two techniques of mobile vision will be pushed by disparate efforts in global film production, predominantly from the start of 1920s through the end of silent cinema. In the first, the shot—and therefore the physical camera along with it—moves without cutting: it changes its angle from a fixed point (a pan, such as the opening shot of the building), or it changes its location (a tracking shot, such as the movement over the photo). The pan operates a form of mobile vision to be made more potent by the tracking shot, as the latter serves to negate its prior perspectives through the shot’s persistence across time. The camera gains new spatial coordinates from which it is impossible to consider the visual field from the previous angle, even with a pan back toward the original position.

The other mode is, of course, montage, the cutting-together of the dissimilar. This mode has two significant functions in Debord’s films. One is the technique most commonly associated with him: the joining together of disparate materials (“scraps”) pulled from the dump of visual culture or else out of active circulation. Here, though, montage manifests its other function in the firm of analytical editing, or découpage:cutting within the same space to reveal more information about it, which is performed both in the urban space of the neighborhood and also over the surface of the still photo.

Lastly, as in all of Debord’s films, there is sound, of three types: music; the sound proper to the “stolen” footage; and, above all, the voice of the narrator. The last sound practice is a supplementary voice that has been interpreted, for almost the entirety of cinema’s history,63 as a betrayal of what cinema can and should do. As François Jost says, “l’image montre, mais ne dit pas”—the image shows, but it doesn’t speak—and open narration is the threat of this confirmation.64 Such voice-over narration has been perennially mocked as the move of the hack or dogmatist, speaking, ultimately, not only of one film’s failure but also of the alleged inadequacy of the image as such, the inability of cinema to express what “should” have been constructed with image and dialogue alone.

V. Still Films

Of these various operations performed by Debord’s films, Giorgio Agamben will focus on montage alone in his attempt “to define certain aspects of Debord’s poetics, or rather of his compositional technique, in the area of cinema,” in his suggestive but flatly wrong account.65 As with my attempt here, Agamben asks after the “close tie between cinema and history,” but his and my answers are as different as our methods. I want to contest his reading and clarify what I understand as that genuinely close tie to be.

What does Agamben assert? At the basis of the argument is an essentially Benjaminian conception of the “dialectical image” as the “very element of historical experience.” This image is then linked to cinema as a specific technology via a Deleuzian account of the “image-movement,” an image that bears a “dynamic tension” of being cut not out of but within history within itself.66

Agamben uses this idea to ground three further concerns. The first concern is to insist on a messianic conception of history, and with it, a messianic conception of the image, “charged with history because it is the door through which the Messiah enters.”67 In his version of things, the prospect of each image providing this point of contact through itself depends on the coming into visibility of the image as means. It is an exhibition of the image “as such” (a qualification that shapes his entire mode of thought), as a “zone of undecidability between the true and the false” and therefore approaching the state of “imagelessness” that shows nothing but the “being-image of the image.”68 The second concern is to insist that this image is the cinematic image and that this framework is both the “situation of cinema” and the “messianic task of cinema,” which Debord confronted and explored, one that he shares “with the Godard of Histoire(s) du cinéma.”69 The third concern is to claim that it is specifically montage that makes possible a connection between cinema and history, as well as the approach toward “imagelessness” that one finds in the work of both Debord and Godard. This interpretation emerges from how their montage relates to the “transcendentals”—i.e. to “the conditions of possibility for something”—of montage: repetition and stoppage, which Agamben grasps as the transcendental conditions of cinema’s animated halting as such.

From this point on, Agamben asserts, “cinema will now be made on the basis of images from cinema,” and the work of those such as Debord and Godard will approach the image as such by taking on its means as without end.70 Crucially, the means are not montage as a technique, directed toward the end of narrative, but the image processed and revealed as image by montage: “images from cinema,” picked up and repeated. So unlike the expressive act fulfilled when, “the means, the medium is no longer perceived as such,” but “the image worked by repetition and stoppage is a means, a medium, that does not disappear in what it makes visible. It is what I would call a ‘pure means,’ one that shows itself as such.”71

Elsewhere in Agamben’s work, “pure means” will be named “gesture,” although the term curiously never appears in his text on Debord. The gesture is a mode in which “nothing is being produced or acted, but rather something is being endured and supported.”72 Repetition and stoppage in Debord and Godard, then, will be the transcendentals to be endured and supported, and “the image worked by repetition and stoppage”—which, crucially, for Agamben remains tied to montage—becomes the gesture, through the becoming visible of the means of montage as such.73

To assert this, in the case of Debord’s films, implies that the assembly of the pseudo-image, via montage, would restore it as montaged image to history and allow it to exceed its status as either pseudo-motion or the movement of the negative itself. It would mean, therefore, going against what Debord actually said about his own work within cinema, including in the films themselves.

To be sure, one shouldn’t automatically trust Debord more than Agamben when making sense of what the films actually do, which is something other than what they were supposed to do. But one should also aim to assert claims that actually correspond to how those cinematic operations work, as opposed to how they might correspond with one’s preferred theory of history. And that actual correspondence is as markedly absent from Agamben’s position as are other crucial elements of Debord’s cinematic practice.

Consider the comparison made three times: that of Debord to Godard, uneasy bedfellows if there ever were, at least from Debord’s perspective. Agamben claims that their cinema is:

a power of stoppage that works on the image itself, that pulls it away from the narrative power to exhibit it as such. It is in this sense that Debord in his films and Godard in his Histoire(s) both work with the power of stoppage.74

There is no doubt that Godard and Debord are both working with the separating of the pre-existing/found/recycled/stolen image from its narrative end. But how?

Regarding Histoire(s) du cinéma, the means of this “power of stoppage” aren’t even on film: as Agamben neglects to remember, it is a video project and visibly so, from the texture of the image to the use of effects particular to that medium. Nevertheless, even discounting that, the two main operations of stoppage in Godard’s practice are fundamentally different from Debord’s. First, Histoire(s) slows down the borrowed footage so that it creeps by, often one frame at a time. Yet as it is video, rather than film, the image does not go black in the space between frames,75 a film-specific condition of shuttering darkness that forms the crux of Debord’s Hurlements en faveur de Sade. In Histoir(e)s, the image remain, halted, awkwardly caught between media. (Most of the material Godard uses is from films telecine-ed to video, such that the video preserves the flicker of film despite being a medium that can “avoid” that effect.) Second, Histoire(s) layers images and generates interference between layers, both in the use of iris cuts and in the dense texture of overlays from stills or films, drawn from different sources and points in the cinematic century. They blur and occlude one another, moving at different speeds rather than being subjected to a unifying frame rate. In this unvanishing slowing and thick interference, Histoire(s) brings montage to simultaneity and proximity, packed into a single frame, and it is this entire image that moves or halts unevenly across time. In the case of Godard’s Histoire(s), then, Agamben’s theory is apt, because there is no other cinematic work in the last century so explicitly and extensively engaged with the texture of messianic time as a means of montage and historically determined “mediality” through which the restoration of history comes.

However, what is the constitutive form of stoppage in Debord? It is there in that sequence of Sur le passage described above: the filming of a still image and an analysis of its surface as though it were a volumetric space to be entered, by cutting closer onto different portions and panning or tracking over its surface.76 But such entrance is barred to the pseudo-image of a filmed image or screen, to the flatness that will be treated as though depth. Moving reveals no new visual data. It just points, a deixis to direct the eye to what refuses to change.

Why isolate this, as opposed to montage, as the crucial operation? Consider the effect it generates. At the start of Sur le passage, similar means are used, but the motion of the camera looks at urban space and opens up information that previously could not be seen. We understand, for good reason, that the camera is moving in three-dimensional space. The same, however, holds for the analysis of the photo. We move in three-dimensional space in front of a flatness, faced with a surface and stoppage that can’t be breached and can only repeat itself. It will take a reverse shot to provide new information, but that too will be stuck and static. (A missed opportunity in the film: a reverse shot to the back of the photograph, to its imageless side…) Because once this procedure has been introduced, it constitutes a second screen that cannot be evacuated, as if whatever we see, even that which is explored as if in space and depth by a camera, is projected on a flat surface, a second screen that a second camera films.

This logic of the pseudo is contagious, and it spreads, such that retroactively, even the preceding neighborhood shots become film of filmed images, not film of a city. Light and angle threaten to become off-screen glare and anamorphic distortion. Cinema will indeed be made on the basis of images from cinema, but as a negation and secondary imitation of cinematic experience. We watch our own separation as process.

That is the “situation of cinema” Debord confronted, and it runs fully counter to a messianic conception of history. Like that conception, it frees up the hostilities buried within what appears as depth by means of insisting on its surface as means. But it does not understand that pseudo-image as the point of entrance for history’s salvation. Rather, it is simply a leveling down to the ground of ruins that have long been the case.

VI: The Ekphrastic Gesture

Returning once more to the frame for this whole investigation, that of accumulation and its impasses, the technique of the “second screen” I am isolating here is important insofar as it works to formally narrow the gap between negation and destruction by conditioning all images as if they were leftover, ruined, or fragmented, even when filmed anew. The second screen therefore transforms the pseudo—the space of that gap—from a peculiar property to a general condition, finding it everywhere it looks. As suggested, the danger of this kind of creeping negation is that it threatens to becomes identical to a specifically capitalist process of valorization, rendering all potentially commensurable in an unbinding that ends in the bad universality of exchange. The next aspect of this cinematic practice, beyond whatever Debord or others claimed for or about it, is a doubling-back into the filmed materials, the off-screen, and the connections between, precisely in order to extend negation toward real decomposition, rather than preservation and dominance of the inadequate (ideology).

There are three specific moves made by the films worth identifying on this front, of special relevance because each gestures to real uncertainty about that declared dismissal of the image.

First, return: worrying away at a single still image; coming back to it recurrently over the film’s span. This can both hint toward the presence of an unknown something to be grasped in even the most industrial of images and also generate something like a partial Kuleshov effect, insofar as the same visual data takes on different expressivity in relation to what surrounds it. This is particularly evident in In girum, with the image of the family in the living room to which the film returns incessantly, as well as the image of the boy shopping with what is coded as his mother. As remarked in the textual description (“Reprise de la photographie publicitaire déjà longuement étudiée, de la famille d’employés moderns dans sa pièce principale, avec lent travelling vers le centre”), this is thought as a reprise, a taking up again that finds its wider echo at the end of the film where text printed on screen insists that it is “to be taken up again from the beginning.”77 Yet this reprisal generates only a further gap between a potential expression and an apparent opacity, as if to tell the viewer again and again that there is more to see without ever giving that more itself in its particularity. The repetition through the same image only hollows it out further, until it is just a point of rhythm, a touchstone between sequences.

Second, reversal: the reverse shot,” which is identified in In girum… , along with “a tracking shot across the fleeting ideas of an era,” as the only other element of the “language of this outdated art” that he “wishes to preserve.”78 In particular, the films aim for a reverse shot that has been heretofore lacking, from what does not get to see to what is hidden from being seen: cutting to the other side of the table, angling back from “the viewpoint of the monument,” or, at the start of In girum, looking back at the cinema audience through the projection screen as if it was a one-way mirror. This reversal cuts back against the second screen (i.e. the treatment of all images as re-filmed and belonging to another original source). It also complicates the return to the same image, making of it a composite reverse shot out from within that “image-scrap” onto the other materials that surround it, a shot that turns out to be surprisingly mobile. The combination of the return and the reversal therefore opens up the prospect of moving from the total stasis of the pseudo-image towards a more inflected decomposition.

That actual movement comes with the third mode: ekphrasis, or the description in one medium of a text or object from belonging to another medium. Here ekphrasis takes the form of narration, description, and commentary, both outside the films (their “screenplays”) and spoken within them. If one side of Debord’s cinema turns on the analysis of the still image, ekphrasis is its inseparable other, its formal insistence on the surplus of images. And like that analysis, both the voice within the films and their external textual apparatus are entirely missing from Agamben’s reading, for the simple reason that they are incompatible with it.