O

Rebekah Rutkoff

Top: Artist Pawel Wojtasik’s bathroom, Brooklyn, New York.

Bottom: Women’s bathroom, New York Psychoanalytic Institute.

A Dialogue with Oprah Winfrey

Q: I imagine your trainer, Bob Greene, has an internal knot—on the one hand, he’s Oprah’s trainer, so that opens up product and marketing opportunities, and on the other, he has no authority: you haven’t kept the weight off.

A: At a certain point I said to him, “Bob, you have my blessing if you want to go. But I would love to be able to continue giving you baskets of my Favorite Things if you stay.”

Q: But “Oprah’s Favorite Things” are geared toward women, aren’t they?

A: Stedman lives in the merino-cashmere slipper socks when we’re in Vail. They have rubber traction—they’re like a deconstructed driving moccasin. I don’t know why it’s so hard for us to accept that our men need swaddling too.

Q: Stedman’s a baby?

A: No. And neither were Oprah’s viewers. Someone like Ellen gives baby gifts to celebrities—as if Sarah Michelle Gellar needs a rococo basinet gratis. It’s called overcompensating for being a lesbian. Gayle always said I should tuck a few of my karma points into the gift baskets because I’ve given away so much that my own basket is overflowing.

Q: When you lost all that weight in 1988, you pulled a red wagon with 67 pounds of fat onto the stage wearing a black turtleneck sweater tucked into Calvin Klein jeans.

A: I was thrilled that I had drunk myself skinny with Optifast in four months. I wanted each episode to be worth a year of therapy for my viewers.

Q: So the fat was like Sean Landers’ 451 page hand-written memoir [sic]—if it had been rendered in lard and had no words?

A: I would have respected Sean’s piece a lot more if he’d started it off with “Dear Mom” or “Dear Ann Landers” and then dropped it in the mail and waited quietly for a reply. Sometimes if you can find a celebrity with your own name you don’t have to become one.

Q: But you didn’t lose 67 pounds of actual fat. Weight loss is 30% water.

A: A couple of days before we did the ribbon-cutting at Harpo Productions in Chicago, I sat with Alan Greenspan in his apartment in Georgetown. It’s elegant—I can see why Andrea Mitchell came over for a drink after their first date and essentially never left—it has a high-end soap opera aesthetic with floating slate stairs and an overall taupe and steel blue ambiance, like As the World Turns. I signed a contract, more or less saying that when in doubt I’d err on the side of the interests of free market capitalism. Phil Donahue had given me Alan’s contact—he said it was like going for a few sessions of couples counseling before getting married. So it was a compromise I made with my eyes open. And then we toasted with some 1787 Château Margaux.

Q: Does Alan attend Jeffrey Goldberg’s DC Torah study group with David Brooks and David Gregory?

A: No. Alan davens alone. He said to think of capitalism as a golden rod—keep bending it as far as you can, but when the metallic surface starts to crack and flake off (it’s spray-painted gold), you’ve got to back off so others can keep using it. He said, “Oprah, you’re our Wounded Healer: maintain a low-grade infection without going into sepsis.” I had to promise to foreswear therapy as long as The Oprah Show was on the air to keep the wound moist and protect the brand.

Q: Was Andrea around when you were at the apartment?

A: No. She and Candice Bergen were meeting for lunch for the first time since they were classmates at Penn. After Louis Malle got sick and Andrea went blonde, the power dynamic between them finally gave way.

Q: I spent Career Day in high school with Mona Scott at WCMH in Columbus. She was blonde and it turned out we had the same lambswool charcoal-colored cardigan from Benetton. She was married to Doug Adair and they co-anchored the local news.

A: You’ll be hard-pressed to find a female newscaster who isn’t married. The gift economy of seated TV journalism is off the charts.

Q: But you and Stedman didn’t marry.

A: I knew I was taking a risk by walking around en plain air on The Oprah Winfrey Show. Whenever I watch Diane Sawyer, I think, wow—you won the lottery. The rushing around to meet world leaders in pants over hose, skimming the producer’s notes in a plush leather binder on the way to the UN, cackling with Mike Nichols at night, bothering to stock up on kefir for fruit smoothies so her gut doesn’t leak on the weekends. The way she leans forward in the chair, savoring the outpouring of words: this is as close as you can get to being present while remaining totally blind.

Braves coach Bobby Cox, Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY

Top: The Fathers of the Church, Labyrinth Bookstore, Princeton University.

Bottom: Window display, ABC Home and Carpet, New York City.

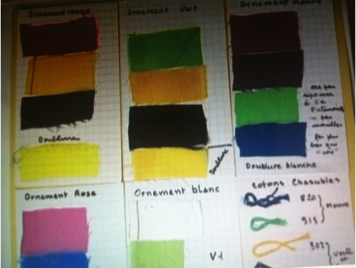

Top: Fabric swatches for the Chapel of the Rosary at Vence.

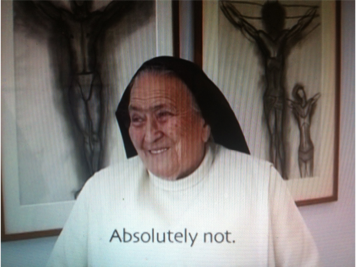

Bottom: Sister Jacques-Marie responds to “Was Matisse in love with you?”

Dressing room door, Urban Outfitters, NYC.

Q: It’s sort of like walking around the perimeter of Serra’s Torqued Ellipses, as close as you can get without touching the rusty steel. You get to make contact with an ideal mother and father all at once – there’s both gentle recognition and the spirit of unwavering authority. You passively follow the line of his torque and get rewarded by an internal liveliness.

A: Serra needs your body as much as you need his.

Q: So people like Diane and Jane Pauley safeguard the state in exchange for femininity?

A: It’s difficult. By the time you learn to read the news properly—to be in control of the rhythm of delivery, and then master enough of the information so that you don’t get caught in an embarrassing situation—there’s not a lot of subjectivity left over. You have to report on Dick Cheney’s heart transplant, be competent about the technology and the surgical terms, keep the diction fluid and the affect consistent and in the meantime you’ve had to get a sitter in order to be able to report from Walter Reed before the surgeons arrive to scrub up at 5:00 AM. Being a newscaster is basically feeling grateful for the self-ordering and access to language that come from lending your body and mind to supporting the Establishment and then converting that gratitude into forms of care and kindness that can’t be argued with.

But don’t forget that the chair is padded. Even though you’re wearing something uncomfortable, you feel contained, and because of hair and make-up there’s a kind of rightness about extending into space. Your nails and lashes lead the way. The fact that your hair doesn’t move when you do gives you a sense of the best kind of female citizenship. And then when you have spontaneous moments—like everyone gangs up on the weather guy or there’s some unintended sexual pun—the gratification is over the top. You get to manage authority and play in a space of seconds, and that combined with the lights and the crew—you just feel happy to be alive.

Q: Is sounds like Michael Balint’s patient who did a somersault in the middle of a session.

A: No. That was a full-bodied gesture of non-compliance, available to a basic fault patient for representation strictly in the therapeutic environment. That patient had been lying down. The spontaneity I’m talking about takes place within the context of the phallic swap-mart of TV. In the chair.

French children returning from an island, 2013.

Notes

Rebekah Rutkoff was the 2013-2014 Hannah Seeger Davis Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Hellenic Studies at Princeton University. She is currently writing a book on the relationship between the cinema of Gregory Markopoulos and ancient healing practices.