CHAOS PHAOS: Markopoulos and Cinematic Withholding

Rebekah Rutkoff

1. ARCADIA

In June of 2008, 150 pilgrims gathered in the remote mountains of Arcadia in the Peloponnese to watch Orders III-V of the American avant-garde filmmaker Gregory Markopoulos’ 80-hour Eniaios at an event and site called the Temenos. Townspeople welcomed us in Lyssaraia with grilled meat and local wine. Diagonal sunrays shot out of a gathering of clouds like a Divine Mercy painting, and the sky was so low and at ease among the rows of receding mountains that the sunset appeared to rise from the ground. Lyssaraia was the birthplace of Markopoulos’ father, who emigrated to Toledo, OH, where Markopoulos was born in 1928 but spoke only Greek until age six. It has a winter population of 10, including one child and one woman. The landscape is dry and brittle — covered in tall fawn-colored vegetation — but it’s full of discrete nuggets of both moisture (honey, olives, figs) and form: brightly colored wooden cubes (bee boxes) line the roads, and shrines, miniature churches crowded with icons, appear as mountainside markers of death. Markopoulos kept his Eniaios images discrete and protected too: not only are most one frame long, but no two touch: each is separated from the next by lengths of black and clear film.

Markopoulos, a self-professed “perennial exile,” made his first 8mm film at age 12. He created ambitious films, starting in the late 40s, inspired by mythic and poetic texts. His models were literary: Plato, Aeschylus, Hawthorne, Cocteau, Balzac. His complex psychodramas and romantic meditations used symbolic color and rapid montage, and in the mid-60s he began to work with very short film phrases that, he said, evoked “thought images.” In 1966 he started to construct shorter portrait films in-camera, running a single roll of film stock back and forth so that groups of frames were exposed or re-exposed at predetermined points and no subsequent editing was required. A central figure in the New American Cinema group in the 1960s, he was also a prolific writer, publishing frequently in Jonas Mekas’ Film Culture.

The Illiac Passion, 1967 (courtesy of Temenos Archive)

But Markopoulos grew disgusted with screening and distribution conditions, and critical of the stifling of artists’ intentions by the “bad monies and grim politicizing” of institutional interests and curatorial egos.2 In 1967 he and his partner Robert Beavers, also a filmmaker, left the U.S. for Europe, hoping to find more support, and the two spent the next several decades there in self-imposed exile. Once abroad, Markopoulos refused screenings, removing his films from distribution and demanding the excision of a chapter about his work from P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film. He grew increasingly focused on controlling the conditions under which his films were seen; the delicate and, in his words, “divine” potential of film was too easily damaged when the artist ceded screening responsibility to curators and institutions with their own priorities, both financial and psychological. He wished to bring spectators into unsullied contact with the medium in a context that would support its singular powers. But frustrations continued. In 1980 organizers cancelled a screening of the Illiac Passion (his 1967 interpretation of Prometheus Bound starring Andy Warhol and Jack Smith) at the National Gallery in Athens when they learned of the film’s substantial nudity. Another screening in Tripoli similarly fell apart. So Markopoulos and Beavers went to Lyssaraia, his ancestral village, and found the spot where his films were meant to be seen. “We chose a site surrounded by terraced fields, suspended in a sparkling atmosphere with a view that reaches to Olympia and the Ionian coast,” Beavers recalled.3

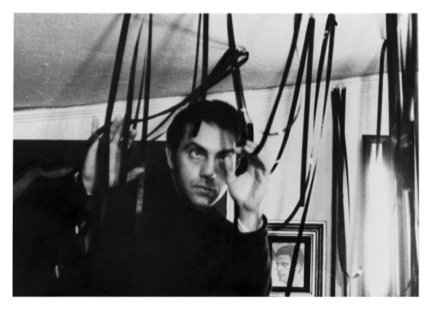

Gregory J. Markopoulos (courtesy of Temenos Archive)

This site was the Temenos (an ancient Greek word meaning “a piece of land set apart for the worship of a god” or “sacred grove”). Markopoulos had been imagining, and writing about, his idea for the Temenos since the early 1970s: it was to function as an open-air theater as well as an archive and library for his and Beavers’ work. But it was this discovery, in 1980, of the actual site that freed him to conceive of his monumental final film, the silent Eniaios (meaning “unity” and “uniqueness”). Made of 55 completely new films as well as re-edited footage from most of his previous films, and meant to supercede them as an integrated epic work, Eniaios contains 100 individual titles in 22 cycles, or orders, of three to five hours each. As mentioned earlier, many images are only one frame long and all are bracketed and isolated from each other by intervening lengths of black and clear leader. The unit of the single frame and the still image were preoccupying, essential elements of cinema for Markopoulos: “It is, perhaps, a fallacy…to believe that film is constant movement,” he said.4 Markopoulos spent the last decade of his life editing Eniaios, but he never saw a single cycle projected; the project was completely edited, but not printed, when he died of lymphoma in 1992. Eniaios has never been seen in its entirety by anyone.

Chaos Phaos is the title of a four-volume collection of Markopoulos’ essays, and the two words compose a miniature poem, an ode to cinema in the form of a biblical dialectic. Chaos is chaos — a formless void; phaos is light — form-giving, object-revealing. Perhaps the phrase is a sibling of the perfect and opposing doubleness of “abandon,” which points both away from and toward the object: to abandon is to renounce, relinquish, disavow, discontinue, lay aside, quit; and to abandon is also to indulge in, give oneself up to, to act with uninhibitedness, wildness, impulsiveness. Markopoulos abandons in both directions: he leaves the U.S., refuses screenings, ceases distribution, stops printing his films. He strips his films of narrative, of sound, of titles, fades and dissolves. In Europe Beavers and Markopoulos shared a highly itinerant life — living only in hotels and pensions in various locales so as not to be depleted by domestic responsibilities. Following the creative impulse, nurturing and sustaining his vision of the divine potential of film, was the greatest priority. But with respect to the second variety of abandonment, I’m less interested here in the filmmaker’s wildness than I am in that of the spectator.

2. A LOVE STORY

The relationship Markopoulos imagines with his ideal spectator is a romantically inflected one. His praise for other members of the New American Cinema scene comes to a halt after meeting Beavers in 1965, and as his roster of acceptable proper names dwindles, his articulation of the Temenos spectator is elaborated. In a 1965 letter to Beavers who has asked for counsel on becoming a filmmaker, Markopoulos describes “the deepest relation,” “the blossom . . . part[ed]” to “those few . . . spectators” who will understand a filmmaker’s work.5 In 1971, he writes: “Beloved spectators of my distant Temenos, what evolved was . . . a continuous working decision not to betray you . . . not to impose a message in your laps . . . I have always been concerned for you.”6

Those tempted to respond to Markopoulos’ articulation of the spectator-as-mirror with a charge of narcissism (“Who will inherit the Complete Order of Works by Beavers and Markopoulos? . . . Those who . . . have the capacity to love”) are not alone.7 “I had often been accused of being narcissistic, just as later I was accused of being self-indulgent,” he writes in 1968.8 But the question of grandiosity — one that sometimes gets intertwined with discomfort about the inaccessibility of the Temenos, the literal remoteness and very challenging form of Eniaios — need not threaten us. I don’t mean threaten us as in scare us, but threaten us by allowing disgust or skepticism to obstruct the possibility of abandonment. I would suggest, in fact, that the centrality of the spectator in Markopoulos’ vision is radical — his fervent demand for “vital communion” is accompanied by a supreme challenge, and freedom: “The creative film spectator[s] who would pursue the Indian trails of the New American Cinema . . . must spin their own threads of reality and weave their own patterns of intelligibility.”9 He is looking for a spectator as imaginatively liberated, as willing to “subdue the common meaning of time,” as he is.

But Markopoulos had anticipated a kind of speechlessness even among his most perfect spectators — an unconscious state of having been moved without a capacity to articulate it. Against the thousands of pages of his own output, Markopoulos predicted that the spectator would not be able to render her Temenos experience in linguistic terms. “Like myth, it will operate in un-seen ways,” he wrote. “The spectator may not realize what is being shown on screen, but, as in the use of myth, it doesn’t really matter, because they may think that they’re not actually understanding something but they are nevertheless.”10 Perhaps Markopoulos, who saw himself as offering a cinematic gift with therapeutic potential, did not know that cure is dependent on representation surfacing to a conscious level. To give in to the Temenos, then, is to go beyond Markopoulos’s prediction of speechlessness.

Markopoulos and Beavers at the Temenos site, 1980s (courtesy of Temenos Archive)

3. INCUBATION

When the sun went down on the first of three nights of screening in 2008, Beavers, organizer of the Temenos (where portions of Eniaios have screened every four years since 2004) offered spare guidance. He gave us permission to fall asleep: “Let the mind wander,” he said. “Do not worry about retaining the images.” He also warned against allowing the mind to dominate the body: “Don’t analyze,” he said. “Just see.” And he invoked the Greek god of healing Asclepios. Ancient pilgrims, ailing and seeking a cure, slept inside the god’s sanctuary in a state of enkoimesis, or incubation. The next morning a priest interpreted the resulting dreams and found in them the counsel of the god. Inspired by the model of Asclepion healing, Markopoulos envisioned himself as a “Filmmaker-Physician”; he conceived of the spacing among the flickering images in Eniaios in the hopes of nurturing in his spectators a therapeutic form of incubation. He wanted to offer his spectator-pilgrims a cinematic cure. “In the Temenos the visual incubation shall be the metaphysical journey,” Markopoulos wrote.11 He hoped Eniaios images might impress themselves in unconscious areas, stirring up dormant zones of spirit and psyche.

I knew almost nothing about Markopoulos’ films — I had seen only one of his films one time, just eight months before, so Beavers’ brief mention of Asclepios offered a welcome structure with which to contain the daunting stimulations of the coming days. When I reached back to the dream I had had the night before, my first in Greece, I saw that incubation had already begun. I had dreamt of a man, a New Yorker, TV producer, and hustler, whose seductions I could only partially resist. He had the oversized and suited body of Wallace Stevens, and a never-ending apartment of jewel-colored rooms. My feelings about this man were mixed: the old-fashioned aura of show-biz around him struck me as corrupt, but time alone in his apartment led me to gather the possibility of his depths. I learned that he had spent time in Europe as a young man — in snapshots he was tan and wore a white uniform. And after a nap and a face-washing I met him at a leather booth for brandy. And then he created a wild spectacle in the middle of a green park lawn.

He had assembled a bouquet of golf clubs, and attached to the top of each a spray of colored feathers, mimicking a blossom. At the last minute a woman searched for a dark blue feather — the tableau of colors was not correctly balanced, and the addition of blue to one corner of the bouquet-top fixed the composition. And then a handful of children helped send the bouquet into the air; it grew bigger according to my lifted vantage point in the sky. The man was a spectacle-maker. He had launched the feather-flowers for the pleasure of the children.

Like an analysand’s first dream, this one was a collage of prefiguration: the picture of a color spectacle in the sky over a lawn (the Temenos screening situation itself); the idea of cleansing and purification rituals (the face-washing, nap and brandy) necessary, according to the conventions of Asclepion mythology, to prepare for the incubatory dream-state; a deep ambivalence about submitting to a masterful figure whose visionary powers, creative bravura, and maleness are inextricably bound; and a wish for involvement in the creative act (the woman’s blue feather addition) beyond the position of worshipful spectatorship. Indeed, the Temenos presents for some — as it did for me — a dilemma regarding power. I was worried that I had traveled to Greece in order to worship at Markopoulos’ temple.

The sharing of dreams is a tricky undertaking, but I hope my rhetorical point is clear. Dreamwork is the most essential site of transformation and of non-compliance, and, outside psychoanalysis, I can think of no cultural form that makes space for the forgotten givenness and essential labor of dreams as the Temenos does. Given the problem of language and time with respect to dreams — they must accumulate, and interact with the air and the words of waking life, in order for their wishes to be legible — you might say that the 80 hour length of Eniaios is deeply sensible: it gives one a chance, that is, to make dreams a reality.

As Adam Phillips says, psychoanalysis “is a story about fluency and its interruption,” about seeing where the associative chain breaks down, and restoring, with the aid of dreams, onward motion — of language and impulse.12 The capacity to associate is at the heart of both poetic and psychoanalytic cure. But the talking cure also involves the acquisition of fluency in the language field in which disease and cure take place. Doesn’t an analysand inevitably come to know analysis, to articulate it even without textual guidance? What kind of cure comes from knowing a medium?

Eniaios offers a kind of primal-scene access, usually denied, to the dynamics between the acrobatics of the screen itself and the image contained within it. Images are inseparable from their presence against the sky and its drifting constellations, and motion is less a fact of on-screen representation than the result of ever-adjusting eyes and subjective seeing. When an image retreats, giving way to black or clear leader, tremendous motion can collect at the borders of the screen, and it can appear as if framed by light. The recession of light at times has a centrifugal quality, as if the image is a flame burning back into the screen.

Decomposition is a dominant theme: not in the sense of total dematerialization or loss of form, but in the breakdown of conventional units of perception into ever smaller parts. In the die-down of an image a few frames long that’s followed by black, I counted eight stages before my eyes registered true black. Even the falling of night, that fact that ushered in the start-up of projection, revealed its own stages under the auspices of the screen: when projection began, the sky was dark but a handful of clouds still alert; later the sky blackened and stars replaced the clouds.

And because of their brevity, many Eniaois images are impossible to name until repetition has given them more certain form. This frustrates the language impulse in the process of image-intake; in time, anxiety gives way to acclimation and, possibly, incubation.

The separation between images makes possible glimpses of perceptual overlap and bleeding free from their prescribed presence in the form of cross-dissolves and superimpositions; instead the eyes, screen and sky conspire to create these effects. Drama exists at the level of physiology, as pupil expansion and contraction are fully felt phenomena. And relativity reigns: the chance to move about — to go from being cocooned in a bean bag meters from the screen to standing far behind the projector — provides an opportunity to encounter the film, and the whole Temenos scene, in variously sized fields of vision.

Walking to the site on the second evening, I stared at the setting sun for too long, and a constellation of dots with uneven, cartoonish edges flew before my eyes. It looked just like a film I had seen before — Scherzo (1939) by Norman McLaren. I recalled suddenly that I had seen the word scherzo written on the side of a purple and yellow polka-dot box in the window of a closed shop in Megalopolis earlier that day. The box and word had been deposited, but disappeared until the sunspots retrieved them along with McLaren’s tiny film.

4. APPETITES

Markopoulos’ six minute Bliss is an in-camera portrait of the frescoed interior of the 18th century Byzantine Church of St. John on the island of Hydra in Greece — an ode to the transfiguring powers of Aegean light. It was the first he made after leaving the U.S., and it was also the first Markopoulos film I ever saw, in 2007, the one that had made such a strong impression on me that I traveled to the Temenos the following summer based on those six minutes. This past summer I decided to visit the Church of St. John; I arrived on Hydra by ferry, and felt very organized. I had Googled the address of the church ahead of time, and made sure to ask the hotel owner how to get there before I went to sleep. But he had no idea. Cars are prohibited on Hydra, and there are few streets names. As I learned over the course of three days, there are 360 churches on Hydra and seven are called the Church of St. John. All of them are locked all the time; neighboring elders keep the keys.

Church of St. John, Hydra — the location of Markopoulos’ Bliss (R. Rutkoff)

As I arrived at each wrong and locked Church of St. John, my heart beat fast, and as I waited for a little old lady with a key to appear, I worked myself into a pre-visionary state, taking pictures of sun spots and finding cosmic meaning in nearby piles of rocks. Still unsuccessful on the third morning, I attended Mass at the main church on the island and thrust a note in the priest’s hand afterwards, explaining the urgency of my search. “Very difficult,” he replied sternly in English. Later that day I took a donkey to the home of the couple who kept the key to Markopoulos’ Church of St. John. It was on the donkey that I began to feel both humiliated by my quest — as if I were simply modeling my own appetites on those of Markopoulos — and aware of the romantic dynamics of abandonment. The insistence of my wish to find the church was also borne of Markopoulos’ withholding — the Bliss shots are so short, and so layered, that even when I finally entered the church, I did not recognize it as the film’s subject until I saw its light-ringed cupola.

Church of St. John, Hydra — the location of Markopoulos’ Bliss (R. Rutkoff)

In the philologist Karl Kerenyi’s book on Asclepios, Markopoulos underlined a passage about cult temple secrets and wrote a note. “In the Temenos there must be a secret — what secret?” It is only via the proliferation of Temenos spectators’ voices that we might find out.

Notes

Rebekah Rutkoff is a Member at the Institute for Advanced Study in 2015-2016 and the author of The Irresponsible Magician: Essays and Fictions, forthcoming from Semiotext(e) in Fall 2015.

A version of this essay appears in my forthcoming book The Irresponsible Magician: Essays and Fictions (New York: semiotext(e), 2015). Thanks to semiotext(e) for permission to include this piece in World Picture.

Gregory Markopoulos, “Towards a Complete Order,” Film as Film: The Collected Writings of Gregory J. Markopoulos, Ed. Mark Webber (London: Visible Press, 2014), 365.

Tony Pipolo, “An Interview with Robert Beavers,” Millennium Film Journal. (Nos. 32/33 Fall 1998): 31.

Gregory Markopoulos, “The Intuition Space,” Film as Film, 75.

Gregory Markopoulos, “Inherent Limitations,” Film as Film, 68.

Gregory Markopoulos, “The Redeeming of the Contrary,” Film as Film, 275.

Gregory Markopoulos, “ERB and Tree,” Film as Film, 332.

Gregory Markopoulos, “The Adamantine Bridge,” Film as Film, 263.

Gregory Markopoulos, “The Filmmaker as Physician of the Future,” Film as Film, 234.

“Interview with Gregory Markopoulos on Radio Free Europe, May 10, 1966, New York City,” Gregory J. Markopoulos: Mythic Themes, Portraiture, and Films of Place, Ed. John Hanhardt and Matthew Yokobosky (New York: Whitney Museum 1996), 85.

Gregory Markopoulos, “The Complex Illusion,” Film as Film, 360.

Adam Phillips, The Beast in the Nursery: On Curiosity and Other Appetites (New York: Vintage, 1998), 7.