Burn. Object. If.

Eugenie Brinkema

The roof, the roof, the roof is on fire.

The roof, the roof, the roof is on fire.

The roof, the roof, the roof is on fire.

We don’t need no water let the motherfucker burn.

Burn, motherfucker, burn.

—Bloodhound Gang, “Fire Water Burn,”

by way of Rock Master Scott & the Dynamic Three1

“Now one can understand Kandinsky’s famous question:

if the object is destroyed, what should replace it?”

—Michel Henry, Seeing the Invisible2

Burn, motherfucker, burn

The problem, as Émile Cioran insists, is that “La mort est trop exacte; toutes les raisons se trouvent de son côté.”3 It has the all of certainty on its side.

If the object is destroyed

The idealism of sustainability discourses—sustained by notions of futurity, preservation, duration, continuation, endurance, but also production and productivity over time, healthy diversity, maintenance, memory, but also imaginary projection, an ethic toward built and natural environments, therefore mutuality between generations, therefore compromise—each attempting to stave off future disaster (or the future as disaster), the finitude of the species, the finitude of the planet—involves an avowal of futurity, a temporal promise, a common interest, an ideological drive, and anxiety about seeping forms of waste, insufficiency, inefficiency, indolent responses to crisis, suppuration, the untenable, the intolerable, disrepair, dissolution, decomposition—tracking all possible paths of foundational destruction, every thinker a wary termitologist.

For each and every If, precisely, then, a plan.

What should replace it?

The anti-destructive impulse of sustainability in a material sense is different from the question of sustainability in the aesthetic sense, but the same questions can be asked of both: What can form sustain? What sustains form? What should form not be asked to sustain? What is the form of the failure to sustain? What is the relationship between sustained duration and finitude as its limit? What can form sustain even (or especially) in the face of radical unsustainability on the level of textual material? One might even imagine that the terminological building blocks of politicized sustainability discourse—the apparatus that grapples with: waste, disaster (and relief), slums, poverty, over-population, inefficiency, pollution, trash, presentism, spoilage, surplus, the unequal distribution of resources—could be reimagined for aesthetics. When Adrian Parr, meditating on “junkspace,” the derided figure for postmodernity’s (pace Jameson) hallucinatory and unnavigable, appallingly air-conditioned (pace Augé) non-places, writes that it “marks the acceleration of formlessness and mutation. As form withers we are left with a directionless, transitory, indeterminate, promiscuous, and repressive space,” are we not to hear in this the faint possibility of an aesthetic stance, one that recuperates formlessness and mutation, that attempts, precisely to sustain that directionlessness on the level of form?4

—But that is not precisely the question that will sustain this article.

Burn, motherfucker, burn

Directions for Decomposition: Genealogy of Fanaticism — The Anti-Prophet — In the Graveyard of Definitions — Civilization and Frivolity — Dissolving into God — Variations on Death — In the Margin of Moments — Dislocation of Time — Magnificent Futility — 5

If the object is destroyed

To hold, to keep. To hold and to keep.

“To support the efforts, conduct or cause of; to succour, support, back up”; def. 4, “To keep in being; to cause to continue in a certain state; to keep or maintain at the proper level or standard; to preserve the status of.”6 By definition, a conservative gesture, the gesture of conservation—hence the easy rhetoric of accord in the 1987 Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: “In its broadest sense, the strategy for sustainable development aims to promote harmony among human beings and between humanity and nature.”7 (This stance shows all its cards: A commitment to the there of what is there, the here of what is here, an iteration of every logic of presence and the being of what might be—what will be’s rapport with what is.) But to keep and to hold is also a form of pressure, of duration and tension: what is “capable of being borne or endured; supportable, bearable.”8 Always, also, therefore, it involves the re-posing of the sufferer’s question: What, precisely, is bearable? -able, the expression of ability, capacity, possibility, thus actuality What is manageable for fainéant or frenetic forms, what kinds of exertion or indolence result from testing persistence, from enduring, from seeing what can be borne, and what is unendurable, untenable, even intolerable.

Burn, motherfucker, burn

Sustainability’s harmonious pledge or schöpferische Zerstörung—one must choose.

Burn, motherfucker, burn

“In the case of the smallest or of the greatest happiness, however, it is always the same thing that makes happiness happiness: the ability to forget or, expressed in more scholarly fashion, the capacity to feel unhistorically during its duration. He who cannot sink down on the threshold of the moment and forget all the past, who cannot stand balanced like a goddess of victory without growing dizzy and afraid, will never know what happiness is—worse, he will never do anything to make others happy. [. . .] A man who wanted to feel historically through and through would be like one forcibly deprived of sleep, or an animal that had to live only by rumination and ever repeated rumination. [. . .] Or, to express my theme even more simply: there is a degree of sleeplessness, of rumination, of the historical sense, which is harmful and ultimately fatal to the living thing, whether this living thing be a man or a people or a culture.”9

If the object is destroyed

1893

Frozen starvation Death—anticipation

Fatal abortion Insanity Incendiaries

Armed tramps Tramps Window smasher

Black diphtheria Incest Unemployment

Business fairy tales Farm depression

Mill failure Retail failure Bank

examination

Factory failure Retail failure Bank

Failure 10

What should replace it?

Nietzsche is talking about the paralysis of remembering all, the horror of a truly historical consciousness, ever awake without respite from the present. Hence man’s bilious envy of the simple beast who so easily forgets. But is there not also a horror in projecting all—ever imagining into a future that has yet to arrive, continually abandoning the present in order to construct the future state as one that has held up, one that will have kept and held, one now imagined that will have had the fitness to endure what itself has yet to take place? Instead of remembering as a form of history (whereby the antihistorical is figured as forgetting) this active projecting asks that we imagine all, all of the future in advance of leaving the present and only from the point of view of the present as it will be imagined to have been by the all of the future. This is the opposite of the philosopher’s demanded radical forgetting: a furious projecting that remembers precisely all of what has yet to take place. The Brundtland Commission’s oft-cited definition of sustainable development—“development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”—reveals its temporal hand under the pressure of Deleuze’s formulation that “Need is the manner in which this future appears, as the organic form of expectation.”11 In other words, for the present to be defined as a space of need anterior to and separate from the needs of the future, the intratemporal dimension of the present must be elided in the Commission’s account. The present is constantly passing away; sustainability discourse must solidify and thicken it, hold it fast in a photographic pose, imagine its needs as ones not bound to a future, to the form of expectation, but as knowable sites of retroaction on which a politics for that yet-to-arrive future can be based. There is, therefore, a triple projection: of the hypothetically taking-place future as imagined from a present, of a present imagined as a stability, and of the present as a historical but imaginary past that will have extinguished or exhausted some X as imagined by and for the imaginary future.

If the object is destroyed

“The epidemic said by some to be diphtheria, that prevails at Grantsburg among the young people, goes on without abatement. [. . .] The epidemic has given such alarm that it is hard to induce the living to bury the dead. [11/30, State]”12

If the object is destroyed

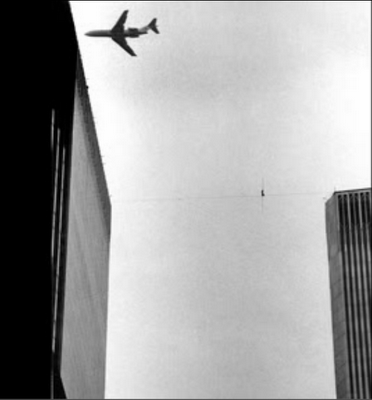

8.46 a.m.

What should replace it?

The aesthetic antidote to sustainability’s over-investment in duration is the non-durational of the extinguished, the ephemeral, the event that is precisely what is un-sustainable; all that which the archive’s attempts to capture and preserve will fail in the face of. What is exhausted in its commission, what does not persist, what evades even the present and answers not at all to an imaginary future; or—what is subject to finitude. All this In praise of the ephemeral, the transitory, the impermanent is worked out on the level of visual and temporal form in four linked sites at two temporal removes: Michael Lesy’s 1973 compilation history Wisconsin Death Trip; James Marsh’s 1999 non-fiction cinematic reimagining of Lesy’s text, which shares the same name; Philippe Petit’s To Reach the Clouds, his poetic account of numerous high-wire walks, including his most famous, between the almost-completed Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York in 1974; and, finally, Marsh’s 2008 documentary about Petit and his extraordinary act, Man on Wire. These texts are determined by forms that come into being only to fade away, forms marked by formlessness and disappearance, forms that are unsustainable and fail to persist, ones that everywhere risk cultivating disaster and that are irresponsible towards the future. A form that does not try to transcend the ephemeral accepts that it will be dismantled.

Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip is about what the historian calls “ten years of loss and disaster.” The text’s database-like quality—archival written records and photographs preserved without system as flattened iterating items (newspaper accounts; records from the local asylum)—suggests analogically the proximate cause given for the horrors contained therein: lack of variety or boredom was thought to have caused anomia, the weakened moral faculty that produced the endlessly intoned murders, thefts, arsons, suicides. In the spirit of the pharmakon by way of Derrida, Lesy’s textual lack of variety, the form’s flat sameness and stubborn repetitions, is both cause of anomia and, in its textual commitment to the infinite possible variations on such horrors—each discrete, strange act unthinkable in its own unique way—simultaneously its cure.

Sustainability is, at heart, conceptually, and regardless of the local context for its invocation, about forms of persistence. Wisconsin Death Trip is a text in which nothing persists on the level of historical material: every figure dies; every window is shattered; every object burns. Lesy even writes, of photographer Charles Van Schaick’s 30,000 glass plate negatives, the ground of his archive, that, left after the photographer’s death for thirty years, “Occasionally, a lower lip or the whole side of a face would crack off and break away like the side of a glacier. Often the edge of a cornice or the crest of a hill would disintegrate into flakes the size of silica sand. The stacks of glass broke because of their own weight; their emulsions decayed because of too much or too little moisture.”13 It is not enough to suggest that what sustains all of these losses—and the only thing that can sustain them—is the text’s and the film’s formal choices; each form, it must be said, is sustained in turn by these overwhelming sites of destruction. Lesy’s textual assemblage and Marsh’s non-fiction film hysterically sustain, through iteration and formal repetitions, something in the face of raw material that is the epitome of the coming-into-being of so many nothingnesses. This attempt to formally sustain—where the totality of the material does not—makes present (in fact, makes overpresent) the multiplicity of the very forms of destruction that fight formal attempts to resist them. By contrast, Marsh’s later film, and Petit’s account of his wire-walking, celebrate precisely the radical aesthetic possibilities of the absolutely unsustainable act.

Marsh’s two films function like a body and its shadow: the earlier one takes the form of a catalogue, a dehierarchized assemblage, while the other encircles, drives towards, a singular event. With Wisconsin Death Trip, from the photographic archive—and it is the single avowal possible from the existence of the archive—we know with certainty that these dark sad people: they once lived. With Man on Wire, we know with certainty, again the archive avows without doubt: Petit was there. The towers, also, their beams and structures and their height, their gleam, the clamor of their becoming, the fog that clung and the stairs and the wind, the elasticity, even the space between each rising keep: they were there too. In the earlier documentary, the photographs are the events that certify the past presence of beings who are now gone; in the later one the act itself is the event that certified a past material and environmental presence now eradicated. Both films pose the question of formal sustainability, targeted towards different structures: in Wisconsin Death Trip, it is the very question of what an archive can sustain, and the sustainability of the assembled form itself; in Man on Wire, sustainability is exhausted in the single commission of the great and impossible act. In the one, the finitude of the archive is at stake, while in the other it is the finitude risked by, and that defines, Petit’s stunning aesthetic event.

Burn, motherfucker, burn

“A horrifying discovery was made at the Rosedale Cemetery in Pardeeville. The grave of Mrs. Sarah Smith was unearthed for the purpose of removing the remains and on opening the coffin it was discovered that she had been buried while in a trance. The body was partly turned over and the right hand was drawn up to the face. The fingers indicated that they had been bitten by the woman on finding herself buried alive. [4/14, State]”14

If the object is destroyed

Instead of historical narrative, or a series of facts, observations, or descriptions about the last decade of the 19th century in an isolated community in Wisconsin, Lesy turns to the affective knot of inner experiences rendered through the exterior form of assemblage and catalogue—but not of events, facts, or observations; rather of formal rhythms and repetitions. Lesy’s avowal of pure ontological certainty—“The pictures you’re about to see are of people who were once actually alive”—is the very one of which Barthes and Bazin write in relation to the photograph; it is paired with an aesthetic rigor that escapes the visual and linguistic form of the compendium altogether: “The text was constructed as music is composed. It was meant to obey its own laws of tone, pitch, rhythm, and repetition.”15 There is a resolute absence of page numbers in Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip; it is uncitable and marked by only blankness where linear progression is inscribed into additive narratives. Instead of developing, the text is, in Lesy’s formulation, “caught between the two covers of the book”—trapped, that is, in and by its entirety and therefore unparsable, one way of being unhistorical. The text does not explain or contextualize its micronomia—it presents, it makes manifest: Lesy’s description of it as an “exercise in historical actuality” belies its equal investment in being an experiment in historical virtuality.

No sense is made, no order, no system: Lesy’s text runs not from birth to death, but from death (of children) to death (of the elderly): not a life cycle structure, but a death cycle. Every being dies in their own improper time. The text moves in a slight rotation of wrongs, from a generational perversion of the child who dies before the older generation, to a causal perversion of the elderly electing to die by their own hand instead of letting a cruel nature take its cruelly natural course.

No sense can be made of the object that is destroyed: “At Cameron a child was born in a family named Dunn. The father, in celebration of the event, is reported to have become intoxicated, and returning home seized the babe and dashed out its brains. He was on the point of strangling his wife when neighbors intervened. [12/8, State].”

No sense can be made of such a list:

1891

Diphtheria Infant death Parricide

Arson Suicide French hermit Death

Memorialized Death memorialized

Obscene letters Violent insanity

Despite its resistance to narrative or meaning, sensuous possibilities on the level of reading do appear: the hard break of the initial consonant in Parricide coming off the soft final th of death; the hissing esses of Arson Suicide, which force the tip of the tongue into a cruel complicity; the repetition with the demotion of the capital letter in Death Memorialized Death memorialized, a repeated memorializing that un-memorializes; the Obscene letters that, because they have not yet appeared, appear to refer to the very letters forming words of the nonsensical chain of signifiers. The rhythmic and textural dimensions of the form sustain something in the face of this catalogue of negation: what is sustained is not life or material, but the affectivity of the descriptions themselves.

One of the most charged sites of this formal and affective investment in both Lesy’s text and Marsh’s film is the word “Admitted,” which takes on a radical status as the figure that interrupts these senseless lists. Always announcing a document from the local asylum, it is each time a singularity; despite the many repetitions, the word punctuates both texts with its odd textual primacy and the rigor of its syntactical formula:

Admitted July 29, 1894. Town of Melrose. Age 65. Born U.S. Widower. Three children, youngest 30 yrs. of age. Railroad employee. Has no property except what is in his trunk. . . . Derangement manifested on subject of ‘Bugs and Flies.’ Blind. . . . Sept. 12th: Sudden attack of vomiting and fainted. . . . Sept. 19: Much better—resisted all attempts at physical examination. . . . Dec. 1st: A bedsore. . . has become gangrenous. Dec. 2nd: Failing—Dec. 5th: Died 7 o’clock p.m. Discharged. —Mendota State, 1894 Record Book (Male, G), p. 434, patient # 6586.16

In Marsh’s film, each iteration of the “Admitted” textual units is whispered, a grainy texture of the voice marking the passages as other, as affective, as difficult forms of breath and form. Admitted to. What is admitted is acknowledged as a certainty, it is conceded or declared to be true or applicable or real or apt. It is also, of course: entry, participation, giving access, affording possibility; language of granting acquiescence: allowing X to enter, letting X come in. A release and a prison, a permission and a law. A subject is admitted, but each admittance itself must be admitted to the historical archive from which Lesy draws, twin asylums. The word’s inscriptive repetition in the text, and whispered, hauntingly intoned aspiration in the film—all spittle, hisses and underbreath—grants this admittance only by absenting or withdrawing a full and present sonic register. It is also, of course, also a declaration, a confession or a divulgence, a forced and sometimes involuntary acknowledgment, sometimes under a kind of raw pressure. It is a tension on the level of free and easy truth-telling. If it is a kind of certainty and access, a verb of proof and presence as a form of undeniability, it is also a kind of doubt and reluctance, a proof of the trace of violence. We know at least since Foucault that the record book of the asylum is this simultaneous site of historical inscription and certainty masking forms of violation, conscription, and forced confession. Admitting, coming clean, entering, avowing, reluctantly avowing—every time the opening repetition a singularity. “Admitted”—Like a formula, a grammar or a syntax—like every death, utterly iterable, identical in certainty but also unintelligible, radically unique, the substitutability of bodies set against what Barthes calls the punctum, the revealing detail that affectively pricks—such as a woman’s nibbled digits, upon finding herself buried alive.

What resists this all-encompassing Admitted is Marsh’s choice of the sussurating voice each time pronouncing the crucial opening word. It recalls Deleuze’s account of the artist who “does not mix another language with his own language, he carves out a nonpreexistent foreign language within his own language. He makes the language itself scream, stutter, stammer, or murmur.”17 The formula firmly established for the asylum entry syntax, no signifying sense need be conveyed; however, the affective sense of what Deleuze calls flexion—the “act of language which fabricates a body for the mind”—involves the fluttering instability of the word and the world, a condition in which “Language itself can be seen to vibrate and stutter.”18 What is each time admitted—in both the sense of allowed entry and confessed to as a form of (affective) truth—is each time this vibration in language, a quivering shiver that runs through the soundtrack to the film, each time upending what can be admitted by form, each time avowing only this stutter, Deleuze’s rhythmic bégaiement.

What should replace it?

Marsh uses Lesy’s photographic archive as events. The anti-hierarchical form, the cinematic analogue of Lesy’s refusal to provide citable page numbers, is the duration and pressure of the formal persistence of the sheer repetition of event after event, superstition after suicide after mania after suicide. Like the figure of breaking glass—which sonically and visually breaks into the film and Lesy’s text at strikingly arbitrary intervals—there is an evental mania for breaking in, for rupture of the clean cold flat surface of a text… like the whiteness of the snow, a blankness that is open and all-possible for the traces that may come to be left. Like the silence in the soundtrack over image, another image, another image of a dead child, each time a dead child, all lines and field, negative and positive spaces, the openness of the unsounding. The film’s visuals center on stark graphics of Midwestern trees, bare branches, white expanse—Melville’s “ghastly whiteness,” the whiteness that terrorizes—all lines and field, the stark starkness of the absolute, the literalizing of metaphysics. One photograph after another of a dead child, a dead child, each time a dead child, and only silence. The stillness of the image against the vitality of a moving baby is an abomination, but also small bit of a small bit of kinetic hope.

If the object is destroyed

Blanchot: “May it be a question of Nothing,

Burn, motherfucker, burn

ever, for Anyone.”19

What should replace it?

What should replace it? Points, knots of sensation, sensitivity. To pause, perhaps to dwell on the affective question of these durational investments in form, in repetition, in exhaustion and that which is marked by a (textual) finitude of being and thought and form. But this intensity is precisely what is at stake in how Petit’s memoir and Marsh’s Man on Wire negotiate the Twin Towers event; the intensity is what is impossible to sustain, what is untenable, what will not hold up even in the commission of the act—indeed, what must not hold up so that the act may take place. The event is not bearable; that negation is what this event is.

In Logique du sens, “Ninth Series of the Problematic,” in characterizing the “ideal event,” which is itself a singularity, Deleuze posits: “Singularities are turning points and points of inflection; bottlenecks, knots, foyers, and centers; points of fusion, condensation, and boiling; points of tears and joy, sickness and health, hope and anxiety, ‘sensitive’ points.”20 These affective junctures, or the turning point as a form of affective pressure, are startlingly reminiscent of how Petit describes the wondrous act, the impossible quality of the Twin Towers wire-crossing. Petit calls it “le coup,” the shock, the blow, but also the event, the move, as in a game of strategy:

I approach the edge. I step over the beam.

I place my left foot on the steel rope.

The weight of my body rests on my right leg anchored to the flank of the building.

I still belong to the material world.

Should I ever so slightly shift the weight of my body to the left, my right leg will be unburdened, my right foot will freely meet the wire.

On one side, the mass of a mountain. A life I know.

On the other, the universe of the clouds, so full of unknown that it seems empty to us. Too much space.

Between the two, a thin line on which my being hesitates to distribute whatever

strength it has left.

Around me, no thoughts. Too much space.

At my feet, a wire. Nothing else.

My eyes catch what rises in front of me: the top of the north tower.

Sixty-five yards of wire-rope. The path is drawn.

It’s a straight line. Which rolls on itself. Which sways. Which sags. Which vibrates.

[. . .]

An inner howl assails me, the wild longing to flee.

But it is too late.

The wire is ready.

My heart is so forcibly pressed against that wire, each beat echoes, echoes and casts

each approaching thought into the netherworld.

Decisively, my other foot sets itself onto the cable.21

Deleuze’s question, always, is: What is an event? But Petit’s poetic fragments pose a different question: Where is the event? Is it in the heart or the echoes; does it envelop the body, all that “too much space”? Is the event on one side (the hard built structure, that “life I know”) or the other, the unknown openness of the clouds? Or is the event in the wire, the wire at his feet, the wire that is there, that is ready? Petit’s answer is: none of these; rather, the location of the event is stubbornly not given, remains hypothetical and suspended on the brink of textual arrival: “Should I ever so slightly shift the weight of my body to the left, my right leg will be unburdened, my right foot will freely meet the wire.” The event of the act, the event of the Twin Towers wire-crossing is there where it has yet to take place and where it remains expressible by the exuberant possibility of the modal verb.

In language at once tentative and venturing, like a foot feeling out the balance and the pressure of the wire, Petit’s account bears out all the wild characteristics Deleuze ascribes to the event, the “reversals between future and past, active and passive, cause and effect, more and less, too much and not enough, already and not yet.”22 The future that exists on the other side of that shift in weight is not the same future that can be thought from the position in which that shift has not yet taken place; there is a futility but also a violence in ascertaining the other side of that shift without taking the risk of the changing balance itself. One must protect the Should I ever so slightly—there is an ethic to guarding the unthinkable. The temporality of Petit’s “Should I ever so slightly” suggests uncannily the temporal logic Deleuze settles on for the event, that it is “that which has just happened and that which is about to happen, but never that which is happening.”23 This is not a matter of passage or transition—and certainly not of any decision to step—but rather of an intensity and a weight and a future state of that which will have happened that is never reducible to that which is happening. The act is imperceptible, born out by both text—which leaps from this account to a series of wondrous images—and film—stunned, formally, into the same still photographs and hushed, fragmentary memories of the inadequacy of language for such sights. The stillness of the images acknowledges that this took place even as it suggests the intensity in that which is never happening but is either about to, or has just, happened. And an intensity in relation to that which can never, not ever, happen again.

If the object is destroyed

Petit: “I am invited to sign the beam on the rooftop of the south tower, near the place where the wire and I departed. I sign in indelible ink, so that the inscription may remain indefinitely.”24

If the object is destroyed

The disaster has already taken place. If the destructions and declivities (moral, material, formal) of Wisconsin Death Trip are ever taking place from the point of view of a present in possession of the past through the affectless tour of the archive of what has taken place, Man on Wire has only one singular and total destruction, but it is one that cannot be archived.

The disaster has already taken place, but it could not have not taken place from the point of view of the past. It was unthinkable then, and its representation unbearable now.

Marsh’s decision is to mourn this very impossibility: but to do so by showing the towers of the World Trade Center being built. The visual archive is marshaled for scenes of birth in place of scenes of end. Petit’s account argues for the material solidity of the stage for his then-unimaginable feat: “The rest is noise, lots of noise. The cranes are slewing, luffing, and lifting 192,000 tons of steel. Each I-beam, each load-bearing column tree, each truss is numbered by hand before being slung and sent into the sky. And someone always knows precisely how and when to connect the pieces. This goes on for three years.”25 But Marsh deploys the archival birthing pangs against Michael Nyman’s “Memorial” as a polemic about time and form: Instead of sustainability’s imaginary future from a thickened paused present, this resurrective gesture returns to the moment of creation for that which is already gone, to the image of what has failed to be sustained for the future that is now our reflecting present. This renewal of the state of architectural becoming is possible precisely because it is framed through a necessarily ephemeral event. North tower, South tower, each has to be built in order to be conquered in Petit’s le coup, but they also must be built in order to be eradicated. This mourning ritual is the opposite of projection, but a radical introjection of the past as it imagined a false and magnificent future that did not come to be.

Each tower a body born, every body now a corpse.

If the object is destroyed

9.03 a.m.

Burn, motherfucker, burn

That man on the wire also, however, demands a discomforting recognition—and to fail in this recognition is to fail to mourn the towers. The act, the event, the poetics, the film—the totality of Petit’s le coup—is about what kind of event is worth dying for. The joyful violation of the law, the extraordinary act for which its accomplishment is worth risking finitude. What kind of event transcends what has gone missing?

Philip’s friends abandon him, not wanting to be liable for the death of another; his radical need to detach from others is figured as heroic but also a consequence of singular drive. One can always risk the self, however: and the aesthetic act, its greatness and majesty, is deemed absolutely justifiable in the logic and affectivity of the film. There are others who can avow a version of the beautiful death, who say in their own languages, “Now is the time.” Such an acknowledgement remains difficult—that there are things for which one is willing to no longer be. The film pays loving attention to the extraordinary planning of many years, that admired planning—the detailed sketches of the towers, the query: how to smuggle in the requisite equipment, how best to lie—the aching work and aestheticized deceptions, wild falsifications and thrilling surveillance, the requisite strength of will, the guards as enemies to the great and wondrous deed. Aw(e)ful things happen in mornings. Man on Wire mourns by asking us to understand the madness of a risked beautiful death; it does not celebrate, elevate or sentimentalize this risk of the great act—

But the film does admit it.

If the object is destroyed

The wire-walker is threatened everywhere with his own death, of course. But it is not only this possible finitude associated with le coup with which the 2009 film tarries. What comes to an end with the deaths of the towers is the death of a possibility; the new historical era of surveillance, radically complicating if not ending the potential for subversive artistic crimes, is heralded in part by the documentary’s brief aside to footage of Nixon. Era of suspicion, era of paranoia; what those birthed towers foretell is the end of a moment prefigured in the construction of the monuments.

What is being mourned (and the loss attempting to be preserved) in Wisconsin Death Trip is the ontological paradox of what was once alive, and now no longer is; the question: how do you sustain the dead when finitude has all certainty on its side? Man on Wire mourns, however, the event—and asks: how do you sustain the event that itself is not sustainable in its commission in a historical moment that has passed on a stage that has been destroyed? The trace—on the literal level of Petit’s indelible signature—has burned. Through its radical refusal to name that 2001 morning, the film mourns the loss of the conditions of possibility for the event by returning to the birth of its condition of possibility. Those so many losses are mourned by not being there except by re-presenting the conditions surrounding the act that risks that very form of loss.

In other words, Man on Wire gambles as well: it wagers its mourning of the event on the edges of what has disappeared. The question of the sustainability of the aesthetic act is set against the finitude that has already taken place of the material conditions of possibility for the event. But what is captured in the extinguished unrepeatable act is the risk of finitude, Petit’s sacrificial gesture for the sake of what is possible. And that is mourned, for it also seems to have ended.

In film-theoretical terms, Wisconsin Death Trip tarries with the finitude attendant on the photographic image that André Bazin contends grounds the ontology of cinema. The specific dimension of death that Bazin positions alongside photographic indexicality derives from the arts’ relationship to embalming the dead: the “mummy complex” that attempts to evade death through a halting of the temporal progression towards finitude in the ever-present substitution of a stored object “in the hold of life.”26 Bazin theorizes the photographic substrate of classical cinema in relation to “the essentially objective character of photography” and its independence from the intervening human agent in the guise of the artist.27 His well-known conclusion, and the foundational claim of both realist film theory and Lesy’s logic of the archive, is that the “photographic image is the object itself, the object freed from the conditions of time and space that govern it. No matter how fuzzy, distorted, or discolored, no matter how lacking in documentary value the image may be, it shares, by virtue of the very process of its becoming, the being of the model of which it is the reproduction; it is the model.”28 The bond between photographic image and object itself—that light that indexically inscribes an existential relation between the two—is precisely why the archive of the photographic image and the archive of each time a singular death is one and the same in the Wisconsin Death Trip collage.

This obsession with the temporal and objectal objectivity of the photographically-based cinema, however, is only one half of Bazin’s theorization of indexicality. That first aspect of indexical cinema is based on its photographic substrate and is therefore a question of materiality. The second component of Bazinian indexicality involves threat, danger, risk—and it is in relation to the status of the event in Man on Wire that this form of the indexical appears to be definitively lost. In another essay in Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?, Bazin calls for respecting the “spatial unity of an event at the moment when to split it up would change it from something real into something imaginary.”29 This is his famous “Montage Interdit” that prohibits the fragmenting work of editing at moments when the nature of the filmed subject matter requires the unity of space and time. The limitation of montage, then, comes down to its role as “abstract creator of meaning” for, as in the earlier essay, “[e]ssential cinema, seen for once in its pure state [. . .] is to be found in straightforward photographic respect for the unity of space.”30 Aesthetically, as materially in the earlier essay, the real retains its privileged relationship to the cinema. Material ontology and aesthetic ontology are both threatened by the intrusion of the imaginary, here figured as montage’s power to effect false connections.

In his beautiful essay on Bazin’s polemic for these indexical bonds, Serge Daney recasts the love story of realist cinema as one starring “Bazin et les bêtes” in which “the essence of cinema becomes a story about animals.”31 Daney argues that cinema takes shape for Bazin through an encounter with battles, violence and risk in the form of men and animals whose shared space and time poses a chance of death. Bazin praises Chaplin for really being in the lion’s cage in The Circus, and he praises the film for keeping Chaplin, lion, and cage enclosed within the coherent “framework of the screen.”32 The Bazinian law of montage becomes a negative ban on editing that is, for Daney, a positive “function of this risk”—the law, in other words, is converted into an imperative towards risk. As Daney concludes, “You have to go to the point of dying for your images. That’s Bazin’s eroticism.”33 Thus, when specifically “violent incompatibility, a fight to the death” is at stake, one cannot break continuity, but must save representation by interning, mummifying, the confrontation of and with death itself.34 Thus, it is finitude specifically, for Daney, that grounds Bazin’s ontology of the cinema, and we might recast the law thusly: Petit and wire—but also towers, also space between the towers—must be kept within the same frame, a frame that is historical and that is simultaneously formal. It is also, let it be written, now a dead frame, this death frame.

Bazin’s own fascination with (or fetishization of, or eroticism as) risk is the twin of a fascination with (or fetishization of, or eroticism as) the photographic substrate of the cinema: the real unity in a real space and time of a confrontation that risks real death. It is this second dimension of Bazinian indexicality that is at stake in the mourning logic of Man on Wire—the loss of the event after the intercessions of terror, the loss of a capacity to act aesthetically, to act for the possible, to contravene the law for the sake of the event. What has died, and must be mourned, for Marsh, is the sheer joy at risking the finitude of human subjects. Though the event cannot be repeated, the film attempts to stand in for this loss of the possible in affectively mining the eroticism of man on wire, man and wire, in the same frame—that conjoining demanded by the event. The image must hazard something too. Marsh lets the image retain its dimension of threat in the trace of historical contingency: the image of Petit on the wire while an enormous albatross—a giant white airplane—crosses over him, sign of a historical uncanniness that has yet to be imagined. The image is unreadable from its past inscription (meaning nothing) and at the present moment (meaning everything)—the cinematic image in re-presenting this historical impossibility takes the affective risk of mourning into itself. The image accepts our burden of grieving our time. The image, therefore, cannot sustain itself: it is anti-durational, untenable, unsupportable, because it exhausts itself under the formal weight of being nothing more than the pressure of the ephemeral event that at one time happened. The image becomes what cannot brook, what does not keep. It fails to keep in being, does not maintain at the proper level; it preserves no status. It is not capable of being endured; it is un-bearable and it will not hold.

What should replace it?

The image must admit all risk.

If the object is destroyed.

Notes

Eugenie Brinkema is Assistant Professor of Contemporary Literature and Media at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She received her doctorate in 2010 from the Department of Modern Culture and Media at Brown University. Her articles on film, violence, sexuality, and psychoanalysis have appeared in journals including differences, Camera Obscura, Criticism, and Angelaki: A Journal of the Theoretical Humanities. Recent work includes a chapter for the Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Michael Haneke and an article on rough form in pornography.

Bloodhound Gang, “Fire Water Burn.” 1996. Rock Master Scott & the Dynamic Three, “The Roof is on Fire” 1984.

Michel Henry, Seeing the Invisible: On Kandinsky [Voir l’invisible], trans. Scott Davidson (London: Continuum, 2009), 15. The original, from Kandinsky: “A terrifying abyss of all kinds of questions, a wealth of responsibilities stretched before me. And most important of all: What is to replace the missing object?” Wassily Kandinsky, Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art, ed. Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo (New York: Da Capo, 1994), 370.

“Death is too exact; it has all the reasons on its side.” E. M. Cioran, A Short History of Decay [Précis de décomposition], trans. Richard Howard (New York: Arcade Publishing, 1975), 10. French edition, Gallimard 1966 (17).

Adrian Parr, Hijacking Sustainability (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2009), 23. See also Rem Koolhaas, “Junkspace,” Harvard School of Design Guide to Shopping, ed. C. J. Chung (Hong Kong: Taschen, 2002); Fredric Jameson, “Future City,” New Left Review 21 (May-June 2003): 65-79; and Marc Augé, Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity [Non-Lieux, Introduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité], trans. John Howe (London: Verso, 1995).

Cioran 1; subheadings for Chapter 1, “Directions for Decomposition.”

Oxford English Dictionary, entry “Sustain” (326).

Gro Harlem Brundtland, “Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development”; A/42/427 (Oslo, 20 March 1987); available at <http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-02.htm>.

Oxford English Dictionary, entry “Sustainable” (327).

Friedrich Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations [Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen], ed. Daniel Breazeale, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997) 62; emphasis in original.

Michael Lesy, Wisconsin Death Trip (New York: Pantheon, 1973).

Brundtland Commission (1987). Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition [Différence et Répétition], trans. Paul Patton (London: Continuum, 1994), 93.

Lesy.

Lesy, Introduction.

Lesy.

Lesy, Introduction.

Lesy.

Gilles Deleuze, “He stuttered,” Essays Critical and Clinical [Critique et Clinique], trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1997), 110.

Gilles Deleuze, The Logic of Sense [Logique du sens], trans. Mark Lester, ed. Constantin V. Boundas (New York: Columbia UP, 1990) 281. Deleuze, “He stuttered,” 108.

Maurice Blanchot, The Writing of the Disaster [L’Ecriture du désastre], trans. Ann Smock (Lincoln, NE: U of Nebraska P, 1995), 51.

Deleuze, Logic of Sense 52.

Philippe Petit, Man on Wire [To Reach the Clouds] (New York: Skyhorse, 2008), 178-79.

Deleuze, Logic of Sense 8.

Deleuze, Logic of Sense 8.

Petit 230.

Petit 7.

André Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” What is Cinema? vol. 1 [Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?], trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: U of California P, 1967) 9.

Bazin 13.

Bazin 14.

André Bazin, “The Virtues and Limitations of Montage,” What is Cinema? vol. 1 [Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?], trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: U of California P, 1967), 50.

Bazin, “Montage” 46.

Serge Daney, “The Screen of Fantasy (Bazin and Animals)” [“L’Ecran du fantasme (Bazin et les bêtes)”], trans. Mark A. Cohen, Rites of Realism: Essays on Corporeal Cinema, ed. Ivone Margulies (Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2003), 32.

Bazin, “Montage,” 52.

Daney, “The Screen of Fantasy (Bazin and Animals),” 37.

Daney, 33.