Arousal in Ruins: The Color of Love and the Haptic Object of Film History

Elena Gorfinkel

Film History is the Outcome of An Absence. It proceeds by trying to explain the meaning of disappearance of moving images, and the value of these images in the cultural memory of a given period of time . . . If all moving images were available in their ideal state, equally visible in their integrity, there would be no such thing as a history of cinema.

Paolo Cherchi Usai1

It may be that over the history of pornographic cinema the films themselves have not changed so much as the organization of the senses.

Gertrud Koch2

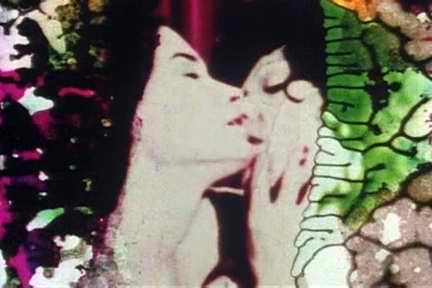

In the numerous and divergent writings on the status, characteristics and historical resonance of cinephilia, a relationship to film is posited, one of an ineffable affection, bordering on obsession, coded through the collection and recollection of ephemeral moments from the cinematic archive. What Paul Willemen, Christian Keathley and others have called the “cinephiliac moment” is studded with a tension, caught between the repetition of a privatized recognition or communion, and the public resonance of a collective identification, both which trade on the traversal of the senses.3 Cinephilia is a narrative of loss and recovery, of the suspension of sublime fragments within filmic memory, as Serge Daney suggests in his comment that “there is a dimension to cinephilia which psychoanalysis knows well under the name of ‘mourning work;’ something is dead, something of which traces, shadows remain.”4 In Peggy Ahwesh’s The Color of Love (1994, 16mm), the “cinephiliac moment” finds its object in the detritus of cinema’s history: the ruin is doubled over, in the appropriation of an extant pornographic reel, an 8mm film which appears to be from the late 1960s. The film strip is in a state of florid decay. The ten-minute film has been re-edited and optically printed to preserve the evidence of deterioration, which appears as a fluid, leaking emulsion on the surface of the image, obstructing vision, forming ornate patterns and resembling an organic presence unto itself.

Ahwesh’s serendipitous discovery of this film in a dumpster positions the filmmaker as a gleaner and archivist, a film historian collecting remnants of an overlooked cinematic past. If we recall, the cinephilia of the Cahiers era, as well as in other historical moments, circulates in some way around low cultural texts, be it the B films of Sam Fuller, Ado Kyrou’s encounter with an Italian exploitation film,5 Paul Willemen’s confession of his attachment to the films of Jess Franco, and Jonas Mekas’ and Andy Warhol’s patronage of skin flicks on 42nd Street. Even in the construction of the velvet light trap architectonic of the Invisible Cinema at Anthology Film Archives in the early 1970s, Annette Michelson observed that, “it was these very features, while conceived as a means of sacralization of the filmic object and essential in the conception of a temple for the ritual celebration of cinema as an artistic practice, that had, from the first, alternatively suggested this structure as an ideally appropriate site for the viewing of pornographic film.”6 All of these anecdotes literalize the “desire for cinema” through a marginalized, low object. We need no reminder that the history of avant-garde practice in film and the plastic arts consistently forged the mutual articulation of art and an eroticized mass culture.

Pornography, popular and unpopular at once, functions as a limit case for filmic representation. In an ontological argument regarding the realist ethos of the cinema forwarded most prominently by Bazin, pornography is seen as perching on the threshold, at the limit of the representable. Bazin’s insights conceive of cinema as a “molding of the object as it exists in time and makes an imprint of the duration of the object.”7 Thus Bazin heralds the principle of indexicality as the privileged function of the cinema, as well as the site for its uncanny effects. Linda Williams has noted how Bazin’s realist ontology collapses at the site of the pornographic and “real” sex, in his essay on Lo Duca’s Eroticism in the Cinema.8 Bazin equivocates, countering his own penchant for the realist tendencies of cinema; he reverts to the benchmarks of imagination and fiction, over and above documentary explicitness, as film’s purest aim, stating that: “actual sexual emotion…is contradictory to the exigencies of art.”9 Bazin goes further in making an analogy between the obscenity of death and sex, suggesting that if a film can show the beginnings of “sexual consummation” he would also have the right to demand that in a “crime film, you really kill the victim…”10 Death becomes the inverse figure of a pornographic ontology. Stanley Cavell makes just as forceful a categorical argument that “the ontological conditions of the motion picture reveal it as inherently pornographic.”11 Thus, pornography becomes film history’s embedded symptom, and Ahwesh’s camera-less film enacts the conflation between the entirety of film history and the pornographic fragment through the traces of the decay that overwhelm the film frame. Thus, linking the pornographic with the cinephiliac via the palpable specter of cinematic mortality, can offer a paradigm for understanding the conditions for the visibility and redemption of the film image in its doubled materiality.

The paradox of Ahwesh’s punk-inflected and feminist cinephilia is in the positing of pornography as its lost object, an object that must be mediated through its immanent destruction. On the one hand, the film refers to and engages the critical debates waged over pornography, disputes that fissured the feminist movement in the 1980s. On the other, the film in its preserved temporality returns us to the approximate historical moment of its production—the late 1960s and early 1970s—and to a period that saw the convergence of the ecstasies and subsequent disillusionments of an international cinephilia; the efflorescence, proliferation, and commercialization for the market for sexually explicit films (in adult cinemas, storefronts, and urban theaters); and the emergence of a politicized, ideologically attuned screen theory, shortly thereafter. These intersecting histories—not teleological occurrences but proximate developments—are summoned by The Color of Love’s dense and complex opacity, its indexicality to cultural, as well as chemical processes, seen in retrospect.

In its melancholic recycling of an extant, decaying stag film—in which two women engage in sexual activity over and with the body of a male “corpse”—The Color of Love proffers its own theorization of the relation of perceiving and receiving senses to film history. Ahwesh’s film is able to create a conceptual bridge between the seemingly opposed realms of history and tactility, using both the suggestive chemical processes that are operating across the physical body of the film, and the epistemological and cultural legacy of pornography.

In his sensitive consideration of the critical legacies of cinephilia, Christian Keathley writes,

“Cinephiliac moments mark not only the recovery of sensuous experience, they also mark the possibility of the recovery of history . . . that is in the very technologies which precipitate the obliteration of history, one finds to use Siegfried Kracauer’s terms, the possibility of its redemption.”12 Ahwesh’s film operates as an illustration of a redemptive cinephiliac moment, a type of core sample rendered historiographic through the material substance of the film strip itself. In positing the failure of technology, the film encourages erotic modes of perceptual experience, re-instantiating the auratic at the site and stilling of disintegration. The failure of cinematic technology—which highlights not the failure of history but the contours of historical conditions of embodied perception—activates a philosophical mode of conceiving sexed spectatorship as coextensive with cinephile modes of looking. Decomposition materializes one instantiation of the “asystematic” contingency of the cinephilic sensibility, as suggested by Mary Ann Doane, yet directs it outwards towards a more generalized horizon of filmic historicity.13 At the same time, a film’s decay inverts the logic of the “cinephiliac moment,” chosen as it is by the conditions of film’s extra-diegetic handling and mishandling, and consequently gestures not to the contingency within the pro-filmic but to the eventuality of the extra-filmic.

Thus, The Color of Love deploys the haptic sense as a political strategy for reorienting eroticized vision toward the film historical past. Embodying an imaging of history, the film invokes an unpredictable, anti-telelological causality—as a field of effects, affects and contacts. The film is the evidence of an exacerbation of chance—in that the culturally denigrated “shameless” object of pornography is the material acted upon by the chemical processes of decay, a certain and allegorical punishment. Deterioration performs an auto-critique of pornography, a reorganization of historical causalities, cultural and political indictments through a materalist literalism. The historical immediacy and sense of “presence” which Ahwesh’s camera-less film embodies is conditioned on a loss, the visible transformation of the film image in the knowledge of its sobering mortality.

Found Footage: Filmic Ruins

Scholarship on found footage consistently returns to the senses of failure, dread, and disaster that seem to inhere within this mode of cinematic practice. Perhaps some of these apocalyptic overtures are informed by recent debates around the possible extinction of film as a viable medium, in light of the encroachment of digital modes of production and exhibition, as well as the difficult politics of film preservation. These effects and affects are also linked to the explicit, artifactual materiality of deploying found film footage. William Wees, discussing the texture of Bruce Conner’s Marilyn Times Five (1973) states, “the repetition of shots and the extreme graininess of the film increasingly draw attention to the body of the film itself, to the films own image-ness. And that. . . is the effect of all found footage films.”14 Catherine Russell implicates found footage films as a genre constitutively mired in the concerns of history and obsolescence,

Found footage filmmaking, otherwise known as collage, montage, or archival film practice, is an aesthetic of ruins. Its intertextuality is always also an allegory of history, a montage of memory traces. . .

And she writes further,

The found image doubles the historical real as both truth and fiction, at once document of history and unreliable evidence of history. Within this slippage of representation, the ethnographic body emerges as a sphere of referentiality. Its indexical claim to the real belongs to a contingent order of time that resists the narrative of history implied by the salvage paradigm, and it is this counternarrative of the memory trace that is produced in found footage filmmaking. The appropriated image may, in fact, be the exemplary dialectical image. Indexicality does not make an image more real or more accurate but inscribes a difference within it that Walter Benjamin understood as the fundamental allegory of the photographic image.15

The origins of The Color of Love are comparably narrativized in terms of ruins, debris; the 8mm reel was found by Ahwesh in a dumpster. Therefore the ontological spontaneity of the “found” in found footage takes on another level of archival significance, as Ahwesh’s authorship is complicated by the existent condition of the silent porn reel. The inscription of difference within the index is doubled in Ahwesh’s film: the memory trace is a memory of a historical moment, of a represented sexual scene. The excess difference is that the footage is pornography. But the physical deterioration of the film is the most privileged testimonial of indexicality to another—extradiegetic—register of the “real.”

The lack or loss of the object is not masked in The Color of Love, as the facticity of the film’s visible chemical decomposition matches melancholia with a reinstatement of cinephilia. That is, the indexicality of the filmic body to history and to decay is conflated with the index of sexed bodies in the porn film. Lyricism and seduction emanates from the meeting of these two constitutively different sets of bodies—the patterns of bleeding emulsion and the pallid, coital nudes—on the tactile surface of the screen.

Elaborating and contextualizing the use of pornography as found footage means asking, what does it mean for pornography to become an historical object which has presumed to have been lost? What sort of “memory trace” is this staged fantasy? Pornography is one of the premier sites for sexuality’s historicity, exposing as it does the conditions of the production of sexualities through representational codes. Russell comments elsewhere that found footage allegorizes the practice of historiography in the instrumentalization of the archive.16 As a retrospective historiography of sexuality, The Color of Love is selective and intensive, rather than temporally extensive. In contrast to Ahwesh’s use of the pornographic text, Ken Jacobs in his Nervous System performance of XCXHXEXRXRXIXEXSX, (1981) extends the duration of a short clip of porn footage, to examine the structural processes of perception. Ahwesh’s film, on the other hand, functions as a “core sample,” a condensation of the pornographic universe into a re-edited, optically printed ten minutes. In the occlusion of vision manifested by the decomposition on the film’s skin, Ahwesh is able to evince arousal out of ruin, re-eroticizing the allegorical image through the logic of its own fatality.

Other uses of pornography as found footage in experimental film practice are diverse.17 In many of these works, the pornographic imagery encourages an editorial focus on the screen surface and the manipulations and obfuscations of that surface. Paul Arthur isolates some of these tendencies of the contemporary avant-garde and its “(anti)romance of the body,” noting, somewhat edgily, that “explicit sexual acts serve as yet another paradigm of de-psychologized solipsistic performance.”18 Pornography’s discourse of excessive visibility necessitates counter-argument that questions the limits and capacities of the form’s production of knowledge through vision. Ahwesh’s film is distinctive in this respect, as it documents the collapse of an embodied vision onto its historically embodied object.

Laura Marks has outlined the ways in which “haptic visuality” engenders an eroticism that acknowledges and embraces the limitations of vision as a sensual faculty. She writes, “haptic looking tends to rest on the surface of its object rather than plunge into depth, tends not to distinguish form so much as discern texture.”19 Although Marks employs video as a site for this play between the haptic and the erotic, she does not exclude the film medium’s capacity to engage with the same synesthetics. In what follows, I would like to assess the haptic in The Color of Love, exploring both the occlusion of vision and the means through which perception is addressed synesthetically and historiographically via the pornographic fragment.

The Dustbin’s Embodied Abstraction

Ahwesh’s intervention and authorial stamp is mediated by the evidential nature of the footage. The filmmaker explains how she discovered the film,

There was one film in a big box of damaged reels and cans in the garbage outside school—and that was the film. On the reel were two regular 8mm porn films—the second being a sun drenched beach cabana sex romp thing with characters seemingly out of UCLA, which didn’t appeal to me… The film had been rained on and stuck together (that’s why some images look double exposed) and wouldn’t go through a projector—the undulations in the picture (the rhythmic pulsing of the emulsion damage) comes from the fact that the area of the film being protected by the spokes of the reel look pretty normal and the other areas exposed got damaged. The film had more scenes—I can’t remember now what–but I improvised on the printer with sections of the film—slowing it down mostly and messed with it in editing until I liked it.20

Apart from editing, optically step printing, and repacing the film, transferring it to 16mm, and adding a lamenting tango by Argentine composer Astor Piazzola, Ahwesh presents the film as it was found, stating “I like it because I found it that way.”21 Ahwesh’s signature is in the speed and pacing of the motion, its synchronization with the sound rhythms, and the temporal guidance of the editing is constitutive to its effects and affects. On initial viewing, however, one can experience skepticism regarding the extent of the filmmaker’s control over the imagery and the state of the print; the decay resembles decisively painterly effects, and this further complicates the film’s epistemic status—a perceptual experience caught between the formal manifestations of the aleatory and the (seemingly) alchemical.

The dye seepage forms alternating patterns on the skin of the film, varying from fine mottled, granular, pixilation-type markings, to large chunky patterns that resemble fleshy intestinal shapes, organic liquid forms, streaming watercolor-like textures, and dense staining blotches. The seeping color varies from deep sanguine red to brownish purple to swampy green and yellow, although the tonality of the red dominates the substrate of the film’s painterly palate. In turn the color of the naked bodies is a flat, drained pallid white, at times the edges of their bodies garner a shade of lurid pinkness. There is no gradation of dark to light, no real perspectival shadow to establish depth of space. The colors all congeal at the surface, invoking an embodied circulation system. The blood motif calls forth not only the film as body but also summons one marker of sexual difference, manifest in the female menses.22

Texture is extraordinarily important as it operates on numerous registers, working both in terms of indexicality (historical knowledge: “this image is decaying”), in terms of associative processes and mimesis, (activation of fantasy: “this shape resembles flesh, bleeding, painting, landscape”), as well as on the level of temporal and spatial interpretation, (“this pattern charts time passing,” “this texture collapses depth,”) and in terms of bodily response and affect (arousal, dizziness, sadness,) all of which require the integration of vision with other bodily senses, most prominently the sense of touch.

The abstraction of these decomposing patterns blankets the naked bodies, alternating from a level of translucency to a dense opacity in which the pulsating moving colors and shapes take over the frame. It is very difficult to take in the film and be able to isolate whole frames, as the patterning forces a certain submission to the motion of the image and an effect of proximity to the image. In this vein, Marks writes,

The viewer is called upon to fill in the gaps in the image, engage with the traces the image leaves. By interacting up close with an image, close enough that figure and ground commingle, the viewer gives up her own sense of separateness from the image . . . When vision is like touch, the object’s touch back may be like a caress, though it may also be violent – a violence not toward the object but towards the viewer . . . Haptic visuality implies making oneself vulnerable to the image, reversing the relation of mastery that characterizes optical viewing.23

Marks assessment illuminates some of the conditions of viewing The Color of Love. I would add, however, that the power and alterity of the image in this film is in the fact of its historical vulnerability. Ahwesh’s film also complicates attributions of subject and object, as the physicality of temporal processes mediates between the action on screen and the viewer, introducing a third term and another position of viewership coded as both historical and sublime. Violence has already been enacted onto the film itself, ostensibly the object, and the viewer acts as its alibi, the witness that satisfies the text’s triangulation of positions, positions unfixed by their allegiance to temporal and material processes. The decomposition can be figured as another object, or itself subjectivated, attributing to it a bodily presence.

The pornographic film is narratively framed by a vampiric, necrophile motif that supports the affect of the morose, decadent, and elegiac: there is fake blood, a dagger, and a heavy red curtain. We need only recall Paul Willemen’s association of the “cinephiliac moment” with “overtones of necrophilia, of relating to something that is dead past, but alive in memory.”24 The dead (or sleeping?) man never revives himself and becomes a prop for the sexual activities between two women. The trope of death precedes the film’s death by disintegration, and the dead man functions allegorically, the “dead object” of porn and heterosexual masculinity. Yet he has to be present, stagily symbolic, to mediate the enactment of “lesbian” sex. He is playing dead, and the women are playing lesbians. This is part of the generic, tacit convention of pornography, and one that this pornographic film, typical and atypical at once, is enacting. Significantly, the fragment that Ahwesh has chosen to comprise the film offers no erection—the man’s penis remains flaccid through the film— and no “money shot,” two staples of the generic phallic “coherence” of commercial pornography.

The film begins with a slowed image of a dense, cracked painterly surface out of which emerges an image of a woman on a bed with a man. There is no depth to the space of the boudoir, and directly behind the bed is a baroque red satin curtain that encases them. Ahwesh edits and repeats her turning over on the bed twice, and her sitting up and turning to the left is followed by a burst of gray moldy film, which obliterates the entire image. Another woman enters and slowly undresses and gets on the bed. A knife is drawn, and we see that the body of the man is indeed a corpse, with (fake) blood on his chest. One woman toyingly outlines his body with the point of the knife, circling his genitals. His un-erect penis is held in close up, and then eclipsed by a fuzzy blot mark on the screen, as one of the women mounts him.

The tempo and sound shifts, as there is a closeup to the woman’s spread vagina, bordered by chromatic fibrillations of decomposition that move from the edges of the screen into the center, paralleling the vaginal lips and mimicking the motion of a curtain. The opening and closing of the curtains seems to act mimetically with the imaginings of a filmic body, which is contracting and expanding. The materialization of sexual sensation takes on the appearance of an imitative body, the filmstrip touching itself, embodying the point of contact between the eye and the screen as a self-regarding caress.

The curtain effect—in concert with and in juxtaposition to the actual red curtain that marks off the bedroom in the profilmic space—is also one of the tropes of retrogression which imbues The Color of Love with an early cinema aesthetic. Antonia Lant has commented on the visual components of the haptic aesthetic of early cinema, and the scrim or screen, which draws attention to flatness.25 The deterioration, which resembles a curtain or scrim, brings the look to the surface of the image, and along with the pallid whiteness of the porn bodies, denies perspectival depth, composing the frame of action along a horizontal axis. Perhaps this retrogression, which can be associated with a kind of “primitivism” taken up by the avant garde, as per Noel Burch, depends on the manipulation of motion in the frame.26 In addition, the original reel has no sound, reinforcing the silent film analogy. The tango music, as its only aural accompaniment, is synchronized with the speed of the images. The tango’s overfull, flooding sentimentality, as John David Rhodes suggests, bears an implicit reference to Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1928), performing an earnest and insistent affective intensity that bleeds over into tinges of histrionic excess, of “showing too much” and implicitly feeling/hearing too much as well.27 The music paces the speed at which we can see the details of the dye seepage, accentuating the mournful tone of affective investment.

This editing technique, of slowing and stilling the image, takes on its most pointed and poignant quality during the sexual interactions between the two amateur porn actresses. The music slows to a crawl as the women kiss, caressing each other’s bodies, while the flow of the chromatic decay undulates around them, as if a halo or protective shield of enclosure. The stop-start motion of the step-printing focuses attention and isolates the shape of the women’s bodies, their facial affectation, and the shapes of the leaking emulsion. The streaming patterns that accompany and border the kiss and embrace have a pulsing effect. The kiss, repeated twice, the second time haltingly slower for emphasis, frames the two bodies of the women in medium close up, the photographic aesthetic seeming for one moment to capture glimpsed evidence of pleasure, as well as structuring the viewers’ pleasure in its most poignant iteration. Is this what has been lost and re-found in the salvaging work of this film? The sexual relation between these two women seems to motor the melancholic feelings and erotic mobilizations of the film. Cinephilia is reinvested here, at the nexus of “primitivism,” arrested motion, lesbian sex and the texturing of vision.

The scene just prior to this one also manipulates temporal disjunctions around the same-sex encounter. One woman leans back with her legs spread as the other massages her reclining body and rubs her genitals. These actions seem to catch the frame, splitting the screen, as if a malfunction in the projection has disordered the coherence of the image; we see the lower half of the reclining woman’s body in both frames, she is doubled in the screen, the hands of the other touching her. Ahwesh’s editing, as the mark of her viewing practice, reinstates the responsive characteristics of the framing cinema to its sexualized content. The instability of the decay is countered with a retrogressive instability that freezes motion, allowing brief moments of reverie and erotic absorption. The rhetoric of insatiability that informs pornography is countered with a calculated repetition and a challenging of teleological progression. In this sense the literalized “lost object” of porn is supplanted by a fantasmatic lost object of an alternative, potentially queer and distinctly feminist spectatorship, which has been foregrounded through the condensation of aesthetic texture and temporal transgression.

The Surrealist filmmaker Germaine Dulac wrote of the virtues of time-lapse cinematography, its ability to condense motion as a feat of synthetic conceptualization:

A grain of wheat sprouts; it is synthetically, again, that we judge its growth. Cinema, by decomposing movement, makes us see, analytically, the beauty of the leap in a series of minor rhythms which accomplish the major rhythm, and, if we look at the sprouting grain, thanks to film, we will no longer have only the synthesis of the moment of growth, but the psychology of this movement. . . The cinema makes us spectators of its bursts toward light and air, by capturing its unconscious, instinctive and mechanical movements.28

While Dulac is speaking of a visualization of growth, Ahwesh’s film operates on an inverse logic, coextensive with the process of decay. The stilling of the frame serves as a temporary and artificial stopping of that decay, at the same time as it “decomposes” movement. The speed of the film comes to signify the onslaught of deterioration, and slowing it down gives access to the mnemonic characteristics of visual address. This arrested moment makes the privileged image visible and accessible, inserting it as a “memory trace,” a reorientation of the uses of the visible. Equally, if not more, affecting as the conceptualization of the sprouting growth, the stilled images throughout The Color of Love accumulate and archive decomposition itself as indelibly tied with moments of cinephile recognition and erotic, tactile spectatorship. Making the “invisible visible,” the motion of time materializes as the decaying inscription on the film strip. Time, in the form of a formal violence which exacts a sensation of fleshiness from inorganic matter, operates on it as it attempts to represent spaces of time.

Making the “invisible visible” also corporealizes the filmstrip itself, as the emulsion makes it appear as though a body is turned inside out, animated as flesh. Being drained of its “content,” color, the “insides” of the film rush to its surfaced exterior, like the draining of a corpse. At the same time that the siphoning off of the color drains the image of its perspectival depth, it produces a spatial conceptualization of the film strip as a body.29 In this regard, it is striking how much the decomposition approximates x-ray photography, a scientific realm of “epistemophilia” which concerns itself with making transparent the surface of the body and specularizing interiority.30 Akira Mizuta Lippit, in a phenomenological excursus on the intersection of the unconscious, cinema and the x-ray, writes: “the x-ray situates the spectacle in its context as a living document even when it depicts, as it frequently does, an image of death or the deterioration of the body that leads to it.”31 What is the impact of seeing the filmstrip as embodied? Whereas the x-ray renders transparency an instrument of depth, and in effect glorifies the effaced surface of the skin in its transposition to screen, The Color of Love situates “liveness” in the emulsification process and its revivification of a sensuous perception. In some regard, this is the central paradox of the film, which motivates sensation and vitalism out of an evidentially perishing object.

The early cinema aesthetic that the film employs also intersects with a pre-cinematic tradition of motion study. Linda Williams has explored the implications and motivations of Eadward Muybridge’s and Etienne Jules Marey’s motion studies for a study of pornography. Motion studies contributed to a technological production of knowledge about bodies and sexual difference that could not be severed from a spectatorial pleasure that depended on the fetishization of the female body.32 If the trajectory of pornography is to make sex visible and make female sexuality speak some truth, as Williams claims, Ahwesh plays with this impulse, arresting motion for an alternatively eroticized enjoyment. Yet Ahwesh’s film seems to both concatenate and complicate three conflicting strata of movement: the movement of the sexed body in the porn film, the movement of the film strip through the projector, and the movement of history along a physical surface. The first term in this series is displaced onto the last term, a syllogism between embodiment and history, and the stop motion effect thus attains a redemptive, preservationist tenor.

The film continues from these moments between the two women to a flurry of activity, the tango playfully speeds up, positions are re-arranged, as the granular and densely laden patterns of disintegration run quickly past the eye, resembling art-ified television static, interference, and sudden blotches of sanguine color. One such abstraction yields to an entirely different scene, and perhaps another space. A seemingly more naturally colorized female body (there is less chromatic decay in sections, making the woman look less vampishly pale), partially dressed, in underwear and opened shirt, lying on her side and masturbating with one hand. The figure is headless, alternately blending with and emerging from the onslaught of throbbing deterioration. The film ends within this equally depthless diegetic space, the final frame stopped on an image of pure seepage and abstraction, cracked dye, bold patterning of red, green and white, with no bodies in view.

Erotic Historicity

The bracketing of the finale of the film within this seemingly disjunctive leap to another space, another scene, another sexual actor and evidently the beginning of the reel of another film (the California sex romp mentioned above)—also raises the question of embodied spectatorship thematically, and in terms of narrativization. Ahwesh explains, “the last shot in The Color of Love—a girl masturbating—is the first shot from that second film. As I was optically printing, it ran into the head of the second film and I ended up using that shot. Kinda like the viewer or the filmmaker, or the whole thing is a dream—some metaphor along those lines.”33 The masturbating observer references cultural anxieties about the indexicality and intentionality of pornography—its mimetic capacity for arousing. The vernacular of porn’s direct effect on the viewing body, its “shame lies in the fact that it has one unequivocal intention: to excite its consumer.” 34 This “corporealized observer,”35 the masturbator-spectator, is the reviled subtextual figure of pornographic reception. As Williams writes, in correction to the presumptions of porn’s engagement with an inaccessible object, “touch is activated, but not aimed at . . . though quite material and palpable, it is not a matter of feeling the absent object represented but of the spectator-observer feeling his or her own body.”36 Ahwesh re-signifies this masturbating figure as a woman, inserting her into the text as a point of identification for her film’s viewers, structuring a fantasy within a fantasy. Conversant with feminist film theory and film practice, Ahwesh asks, “If the lover (man) is gone or dead who activates the film space and conducts the film’s look and where can it go and who killed him off? Can a female point of view enact the film? If the woman leaves the movie in the first scene of The Man Who Envied Women, as a Lacanian gesture, how do you put her back in?”37 Within the impulse towards narrativizing the film, viewers may ask: were the images that preceded her appearance a product of her lascivious imagination? Was what we saw previously a flashback or a travel in time? Was she one of the women involved, now masturbating to the memory of the events? Or was she also watching a pornographic film? Sexuality and reception are orchestrated around the articulation of positions within fantasy. This masturbating figure thus tropes both the female spectator so sought after within two decades of feminist film theory and the feminist cinephile, caught in retrospective repose within her fantasy/ memory; a riposte to the figure of the “dirty old man” which so animates the febrile pornographic imaginary.

As a relay of sensation-effects, the film connects the faculty of touch—in terms of both autoeroticism and the tactile visuality of the molding filmstrip—with a curiosity about historical contexts in light of our own retrospective viewing. Who was the audience for this film? The fact that it is 8mm and silent suggests that it was either a private stag film screened in male spaces of homosocial bonding, such as Elks Clubs and beer halls or a “split beaver” film, an intermediate form between the stag film and the rise of the publicly exhibited hardcore feature, shown in storefronts and on loops in developing red light districts in the late 1960s. However, since most storefront theaters were using 16mm film as a transitional format in this period, the 8mm film Ahwesh found is likely the former—a pornographic film made for the home market.38 The films privatized status, and the exclusion of a possibly female spectatorship, brings us to the presence and presentness of its erotic weight. Ahwesh’s reworking and salvaging of the text, in its mode of address, embraces and installs the female spectator as cinephile. The working of the film is contingent on these series of desires and identifications which structure both the tenor of the lesbian love scenes and of the exteriorized female spectator who speculatively contains or produces the phantasmatic operations which have come before.

Melancholic Archive

Therefore, the question of pornography’s capacity to be a lost object turns out to be somewhat of a ruse. Instead, the evident melancholia present at the sight of the film’s decay is displaced onto two objects. Ahwesh exposes the refused identifications39 that pornography, as a gendered representational system, depends upon, particularly the clichéd formulaic lesbian “number.” By staging the sex between these women as part of the erotic authentication of the text, the refused identification is prohibited from being incorporated into the system of the film and into pornography’s conventional structures of viewership. Having disqualified the structures of visibility that produce pornographic coherence, Ahwesh re-signifies the sexual scene in terms of female pleasure, although there can be a faulty slippage between female pleasure and its representation as lesbian sex. The loss is not of pornography, but of a type of filmic experience, a type of reading practice that Ahwesh is re-constructing and revising. The sensual, tactile elements of the film cling to this constitutive same-sex relation, depend on it for its potency. The mechanisms of sensuous perception are part of this revision. If this was a type of reading that historically has been disallowed by the conditions of exhibition and by the presumptively male audience of pornography, Ahwesh’s re-figuring and selective editing addresses her own audience in terms of seeing the sexual scenes as historically past, but experiencing them in terms of presence. Steven Shaviro expresses this sentiment in his reading of the film:

Watching it, I do not think: “this is happening now.” Rather, I think: “this has happened already.” Nothing is more fleeting than an orgasm, after all. It’s over, almost before it has begun. It happens in the barest sliver of an instant, like the time between one frame of film and the next. But it is surrounded by stretches of empty time, in which nothing happens. A time of infinite longing lies before it. And a time of slow forgetting extends after. The Color of Love is all about these abysses of obliterated time.40

Time obliterated, time emptied out: yet what kind of experience of history does The Color of Love provide? Whose history is it and who has access to it? Despite the artifactual document being accounted for as an object from the late 1960s/early 1970s, it relays less in terms of this era—genre conventions and stag film representations notwithstanding, atypical as they are—and more as a treatise on the process of historical recognition itself. In this way, the film is a historiographic text. Ahwesh’s appropriation places emphasis on the trans-historical motion of the film from one reception sphere to another, particularly in its re-signification as “experimental erotica.”41

This bridges to the second displacement of melancholia, onto the evocation of film history. Figuring pornography, as the “limit” of representation (Bazin, Cavell) and classifying it in analogy to documentary and ethnographic modes42 has furthered this critical/conceptual trajectory. The momentum of the indexicality/intentionality argument, despite its technological and ontological determinism, facilitates the way pornographic film begins to stand in for all film. The Color of Love deploys this status to make a connection between material object-ness and tactility, and the subject of film history. Gavin Smith mournfully and tellingly wrote in Film Comment at the time of the film’s initial release:

What was this film called? Who directed it? Movie history is built on the mainly modest, often worthless, contributions of hundreds of thousands of forgotten—not forgotten, but never known or noticed—lives. Why isn’t it more haunted by the futility of all the work that has vanished into the void? Why does the resurrection of a decaying ten-minute fragment of something whose totality we would consign to that void without a moment’s thought, cause such questions briefly to cross the mind?43

As a fragmentary artifact The Color of Love is able to allegorize a larger body of work, a disappearing archive. Therefore, a contemporary cinephilia transposes the sensation of revelation and private discovery onto the narrative of film history itself. Smith’s lamentations about this allegorical loss address the shunted potentialities, the denied possibilities of future embodied perceptual experiences, which this film has revived. Knowledge of an inaccessible, irrecoverable loss is conditioned, trained by the instance of a single recovery. Jacques Derrida has stressed in his Archive Fever that, “the archive has always been a pledge, and like every pledge a token of the future . . . what is no longer archived in the same way is no longer lived in the same way.”44 Derrida’s concern, with the mutual articulations of the storage of memory and the patterns of lived experience, speaks to the impact of the mode of accumulation of film as documents, their inscription into an embodied practice. The fact that film is already a mode of mechanical reproduction adds another layer of excavation for the archival project of both film historian and viewer.

Smith makes a distinction in the above passage between the loss of memory, the forgetting of uneventful lives, and the lack of knowledge about them, weighting the latter as the more egregious crime. He then directly shifts to a consideration of the lost archive. The crucial point is the unknowability of the depth, breadth, or horizon of the archive as abyss. The fragmentary nature of Ahwesh’s film can only be a metonym in its condensation and saturation, for an irrecoverable site for potential classification. Its melancholy hinges on the cultural capital that is implicit in classification and the assignation of value to cultural texts. Pornographic film can be seen in terms of the hierarchical phylum—genuses, species—of film categorization. But after all, a pornographic film is still a film. The decay, in its most extreme ideation, by moving towards a goal of abstraction and destruction of the original image, will eventually strip the film of its most defining feature, the images which explain it as a genre, as pornography. By positioning the lost archive of film history as that which has yet to be known, Smith is thinking projectively towards the limits of perceptual and spectatorial experience in terms of the limits on what can or can’t be seen, what can or can’t be known, a historical horizon. Christopher Woodward suggests that, “when we contemplate ruins, we contemplate our own future.”45 The irony of such a futurity is not the infinite regress of the reproductive, but the certitude of material dissipation. And in the model of cinephilia outlined by Paul Willemen, the cinephiliac moment allows the viewer to speculate about a filmic “beyond:” “Cinephilia designates that process, indicating that this is an issue in the relationship, a kind of matrix which says that, in the relationship between film and viewer, the film allows you to think or to fantasize a ‘beyond’ of cinema, a world beyond representation which only shimmers through in certain moments of the film.”46 In the case of The Color of Love, that beyond has become a horizon of visibility, entering onto the scene as both the physical imaging of disintegration, and its referential effect of pointing to an irrecoverable elsewhere of the cinematic archive. The politics of film preservation are summoned, the raw pragmatic materialism that seems the bottom line of the discipline of film studies. Pornography, not worthy of preservation, is evicted by the governing law, but reconstituted as the materializing object which “reminds” film history of the pleasures and dangers of sensuous, embodied spectatorship, and which reinstalls cinephilia as a function, rather than an effect, of reception. So the cultural fantasy of pornography’s destruction by the archival abyss is imbricated in the use-value of its abstracted lessons about sexuality, recollected as historical memories. Again Derrida can interject here that “the archive takes place at the place of originary and structural breakdown of the said memory,”47 and in this way there is no thinking the archive without the presupposition of destruction, Freud’s death drive. The Color of Love as a ready-made micro-archive, arrives with the dispensations of its own dissolution.

Touch is often conceived as a phenomenon of presence, the definitive mode of contact which forms the impression that haunts Derrida’s reading of Freud, particularly of the “Mystic Writing Pad.” The invention of the mystic writing pad becomes a model for memory and the mnemonic structure of the psyche. Contact is equally crucial to the self-documentation of cinephilia, which recovers from ones’ own sensorium memories of sensuous perception triggered and found in the body of films seen, films which have “pierced” the viewer, in the fashion of Roland Barthes’ punctum.48 The skin of the body is less permeable, yet I would argue that the synesthesia induced by Peggy Ahwesh’s film is able to outline the ways in which the historical impression of death, and indeed, the death of cinema, can leave a trace on vision, enabling the erotic faculties in the process.

Other filmmakers have engaged, before and after the making of The Color of Love, with filmic decay as a compelling historiographic process, one that highlights the chronos of film history through decomposition. Peter Delpeut’s Lyrical Nitrate (1991) and Bill Morrison’s Decasia (2002), as two prominent examples, collect fragments of early cinema’s nitrate era ruins. Morrison scores his images with a soundtrack that emboldens the creeping horror of cinema’s frangibility and evanescence. Mary Ann Doane has deployed Decasia as an exemplar of the continued pull of the materiality of the analogical index of cinema—its “chemical base” —for film theory, in the wake of digital media and its utopian fantasy of a mathematically generated immateriality. Discussing the shroud of Turin as the transformation of index into icon, Doane traces how Decasia, in its effacement of the look through deterioration marks cinema’s fatality; rather than “straining” to see the stain as a movement towards figuration and iconicity, filmic decomposition reverses this signifying chain: “representation returns to the stain, to the sheer non-iconic marker of existence. What is indexed here is the historicity of a medium, a history inextricable from the materiality of its base. In the face of the digital, the image is rematerialized in its vulnerability to destruction.”49 In its mapping of the relationship between cinema’s material substrate and the field of representation, Doane’s insight can just as easily apply to Ahwesh’s film. However, what makes Ahwesh’s work distinct and considerably more radical, in my estimation, is its chosen historical and generic location, and its framing of vision in terms of an explicitly corporeal sexuality. The Color of Love induces another index, the meeting of the spectator’s implied (potentially mimetic) body and the represented bodies on the screen in a form that persists in challenging and cementing cinema’s realist ontology: that of “real” sex.

But “real” death is never too far off. In his treatise on the ultimate cinematic contingency, the filming of death, Andre Bazin writes,

Two moments in life radically rebel against this concession made by consciousness: the sexual act and death. Each is in its own way the absolute negation of objective time, the qualitative instant in its purest form. Like death, love must be experienced and cannot be represented…without violating its nature. This violation is called obscenity. The representation of a real death is also an obscenity, no longer a moral one, as in love, but metaphysical. We do not die twice.50

Ahwesh marries the two tropes and realist spectacles that animate the Bazinian imaginary—explicit sex and death, here allegorized through cinema’s form. Ahwesh playfully illustrates the intertwining of these figures, asking after the motivations of the film: “is the action read as Bataille’s alternate sexual economy on film—an inverted porn and mis-managed act or perverse sex? A murder mystery? The little death and the big one together?”51 The perverse plenitude of The Color of Love preserves, and arrests the moment of film’s death, extending it into a prolonged perpetuity, its process of coming undone paradoxically preserved for our contemplation—in Bazin’s terms re-embalming the scene of failed reproduction, in another reproduction. What better testament then, to the cinema as a viable form than its imminent destruction? Bazin’s investment in the “qualitative instant” somehow rings hollow, as cinema dies multiply—an obscenity that perhaps leaves us in its most rapt fascination, but also continually renegotiates the dividing line between subject and object, living and dead matter.

Therefore, The Color of Love, having presented itself as a lost document recovered by chance from an incomprehensible and unknowable archive, re-directs its melancholia from its pornographic dejection, displacing it in two directions, towards the erotic scene of a staged “lesbian” encounter, held suspended within arrested motion, and towards the allegorization of an impossibly lost film history. Tactility and history are fused at the point of the film’s inscription by historical process, layered over the obstructed pro-filmic lure of sensate and sexed bodies. Offering a revision of history, a way to see film historiographically, and an instantiation of a feminist cinephilia, Ahwesh’s film illuminates the conditions and temporalities of modes of filmic reception, reorganizing the spectatorial senses and locating them in the physicality of mortal and erotic bodies, both animate and inanimate.

Notes

Elena Gorfinkel is Assistant Professor in Art History & Film Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her publications on cinephilia, erotic film culture and sexploitation film include articles in Framework, Cineaste, and the collections Cinephilia: Movies, Love & Memory, and Underground USA: Filmmaking Beyond the Hollywood Canon. She has co-edited, with John David Rhodes, The Place of the Moving Image, (University of Minnesota Press, forthcoming Fall 2011.) Her current book project concerns American sexploitation cinema of the 1960s and its contexts of production and reception.

Film stills courtesy of Peggy Ahwesh.

Paolo Cherchi Usai. “A Model Image, IV. The Art and Aesthetics of Moving Image Destruction.” Stanford Humanities Review 7.2. (1999): 9.

Gertrud Koch, “The Body’s Shadow Realm.” Dirty Looks: Women, Pornography, Power, eds. Pamela Church Gibson & Roma Gibson (London: BFI Publishing, 1993), 26.

Paul Willemen, “Through the Glass Darkly: Cinephilia Reconsidered,” Looks & Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies & Film Theory, (London: BFI, 1994); Christian Keathley, The Wind in the Trees, or Cinephilia & History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006).

Serge Daney, ” Les Cahiers du Cinema, 1968-1977: Interview with Serge Daney,” interview and trans. by Bill Krohn, The Thousand Eyes, Bleecker Street Cinema, New York, 1977. Archived on Steve Erickson’s website: <http://home.earthlink.net/%7Esteevee/Daney_1977.html >(Accessed March 2010.)

Willemen, “Through the Glass Darkly: Notes on Cinephilia,” Looks and Frictions, 236.

Annette Michelson, ” Gnosis and Iconoclasm: A Case Study of Cinephilia,” October 83 (Winter 1998): 5.

Andre Bazin, “Theater and Cinema Part II,” What is Cinema? (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 97.

Andre Bazin, “ Marginal Notes on Eroticism in the Cinema,” What is Cinema? Vol. 2., trans Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 169-175.

Linda Williams, Hard Core: Power Pleasure and the Frenzy of the Visible (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 184-186.

Bazin, “Marginal Notes,” 173.

Stanley Cavell. The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 45.

Keathley, The Wind in the Trees, or Cinephilia & History, 7.

Doane writes regarding the “cinephiliac moment,” “What cinephilia names is when the contingent takes on meaning…whether the moment chosen by the cinephiliac was unprogrammed, unscripted, or outside codification is fundamentally undecidable. It is also inconsequential, since cinephilia hinges not on indexicality, but on the knowledge of indexicality’s potential, a knowledge that paradoxically erases itself. The cinephile sustains a certain belief, an investment in the graspability of the asystematic, the contingent, for which the cinema is the privileged vehicle.” The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, The Archive (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 227.

William Wees, Recycled Images: The Art and Politics of Found Footage Films (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1993), 11.

Catherine Russell, “Archival Apocalypse: Found Footage as Ethnography,” Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999), 238, 252.

Ibid. 240.

A synoptic and partial list includes: Leslie Thornton’s Peggy and Fred in Hell, Abigail Child’s Mayhem,, Naomi Uman’s Removed, M.M. Serra’s L’Amour Fou , Lewis Klahr’s Downs Are Feminine, Scott Stark’s NOEMA, Paul Sharits,’ Piece Mandala/End War, Bradley Eros’ X Times X, Jerry Tartaglia’s Ecce Homo, Luther Price’s Sodom, Dietmar Brehm’s The Murder Mystery, alongside many others.

Paul Arthur, A Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film Since 1965 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 136.

Laura U. Marks, “Haptic Video and Erotics,” Screen, 39: 4 (Winter 1998): 338.

Peggy Ahwesh, interview with the author, May 24, 2005. (n.p.)

Ibid.

Ibid.

Marks, 341.

Willemen, “Through the Glass Darkly,” 227.

Antonia Lant, “Haptical Cinema,” October, no. 75 (1995): 45-73.

Noel Burch, “Primitivism and the Avant Gardes: A Dialectical Approach,” Narrative Apparatus Ideology: A Film Theory Reader, ed. Philip Rosen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 483-506.

John David Rhodes, “Peggy Ahwesh,” Senses of Cinema. November 2003. <http://archive.sensesofcinema.com/contents/directors/03/ahwesh.html > (Accessed February 12, 2010.)

Germaine Dulac, “Visual and Anti-Visual Films.” The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1987), 32. Emphasis added.

Paul Arthur contextualizes the contemporary avant-garde sensibilities which treat the film strip as body: “the conceit of filmic apparatus as filmic body owes little if anything to the conceits of Baudry, Comolli, and others; indeed it might be better understood as an artisanal qualification of apparatus theory, in which sense organs and the responses they elicit, occupy the position, held by academic theory, of psychoperceptual or unconscious processes. Foregrounding the film strip as labile, quasi organic material has roots in Brakhage…yet unlike Brakhage’s metaphors on vision, the tactics of filmmakers such as Ahwesh, Klahr, Phil Solomon, Roger Jacoby and the silt collective are not geared to express inner subjective states but simply to mobilize sensory impressions through optical experience.” Arthur, A Line of Sight, 137.hage…yet unlike Brakhage’s metaphors on vision, the tactics of filmmakers such as Ahwesh, Klahr, Phil Solomon, Roger Jacoby and the silt collective are not geared to express inner subjective states but simply to mobilize sensory impressions through optical experience.” Arthur, A Line of Sight, 137.

Bradley Eros’s film, X Times X (1998) pushes this association to its limit: projecting the images live within the frame of performance, Eros uses two projectors running two reels simultaneously to superimpose footage of x-rays with pornographic footage.

Akira Mizuta Lippit, “Phenomenologies of the Surface: Radiation-Body-Image,” in Collecting Visible Evidence. ed. Jane Gaines and Michael Renov (Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 70.

For two versions of Linda Williams’ investigation of motion studies, see: “Film Body: An Implantation of Perversions,” Narrative Apparatus Ideology, 507-534; and “Pre-History,” in Hard Core: Power Pleasure and the ‘Frenzy of the Visible.’ 34-58.

Peggy Ahwesh, interview with the author, May 2005.

Carol Clover, “Introduction.” Dirty Looks: Women, Pornography, Power. 3.

Linda Williams, “Corporealized Observers: Visual Pornographies and the ‘Carnal Density of Vision.'” Fugitive Images: From Photography to Video, ed. Patrice Petro (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 3-41.

Ibid. 15.

Peggy Ahwesh, interview with the author. May 2005.

For the history of 16mm adult filmmaking in the late 1960s and early 1970s, see Eric Schaefer, “Gauging a Revolution: 16mm Film and the Rise of the Pornographic Feature,” Cinema Journal, Vol 43, No. 1 (Spring 2002): 3-26; Schaefer has also written a synoptic history of 8mm film production for mail order and home viewing, ”Plain Brown Wrapper: Adult Films for the Home Market, 1930-1970,” Looking Past the Screen: Case Studies in American Film History & Method, eds. Jon Lewis and Eric Smoodin (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 201-226.

I am relying here on Judith Butler’s reading of melancholy and identification. Butler argues that heterosexuality is structured by a pervasive melancholia, haunted by a refusal of loss, in the form of an attachment to a love object of the same sex. The subject renounces this homosexual desire, and the loss is incorporated into the ego as an identification. Judith Butler, “Melancholy Gender/ Refused Identification.” The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 132-150.

Steven Shaviro, “ Decomposing: Peggy Ahwesh’s The Color of Love” Stranded in the Jungle. <http://www.shaviro.com/Stranded/17.html> (Accessed March 28, 2010.)

A recent DVD collection of experimental films distributed by Other Cinema takes the title of Xperimental Eros, and includes The Color of Love as well as films by Uman, Street, Klahr and others.

Christian Hansen, Catherine Needham, Bill Nichols, “Pornography, Ethnography and the Discourses of Power.” In Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary, ed. Bill Nichols (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 201-228.

Gavin Smith. “The Way of All Flesh.” Film Comment. Vol 31, No. 4. (July-August 1995): 18.

Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, trans. Eric Prenowitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 18.

Christopher Woodward, In Ruins: A Journey Through History, Art and Literature (NY: Vintage, 2003), 2.

Willemen, 241.

Ibid. 11.

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill & Wang, 1982).

Mary Ann Doane, “The Indexical and the Concept of Medium Specificity,” differences, Vol. 18, No. 1 (2007), 144.

Andre Bazin, “Death Every Afternoon,” Rites of Realism: Essays on Corporeal Cinema, ed. Ivone Margulies (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 30.

Peggy Ahwesh, interview with the author. May 2005.