Historical Omission and Psychic Repression in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights

Tania Modleski

For some time now, I have been interested in pursuing the phenomenon I call “male weepies.” “Weepies” has long been the term used to denigrate women’s films, particularly the melodramas that have been aimed largely at a female audience and that deal with women’s losses and grief/grievances. I have become weary of reading postfeminist denunciations of the “cult of sentimentality,” a phrase typically used to designate white middle-class women’s sphere. To take what is perhaps the most prominent example of a work that criticizes films and novels aimed at a large female audience, Lauren Berlant’s The Female Complaint condemns much female popular culture because it elevates suffering over the “will to socially transformative action.”1 Certainly, however, it is the case that “male” popular culture, while it may endorse action, hardly for the most part endorses political, or “socially transformative,” action. Even more to my point, however, is the fact that male popular culture also frequently indulges in sentimentalized suffering, even if it accompanies (nonpolitical) action. Thus I believe it is time to address films that make men weep, or perhaps more accurately, make us weep for them.

The suffering of men in film is seldom acknowledged as “sentimental” (or if it is, the term is heavily qualified), but rather passes for something more grandiose. Juliana Schiesari’s brilliant book, The Gendering of Melancholia, which has had a major impact on my thinking, argues that male losses have historically been culturally valued and assigned to the glorified category of melancholia while the grief experienced by women over their losses is devalued and labeled as mere “depression.”2 The losses of white women and also, one must add, of people of color are moreover frequently appropriated by men to further aggrandize themselves as melancholy figures whose suffering on behalf of “Others” is culturally accredited.

To give an all too brief and necessarily oversimplified account of melancholia: in “Mourning and Melancholia,” a brief essay which has been hugely influential in contemporary theory, Sigmund Freud discusses the melancholic person as one who has internalized the lost object (a person or an ideal) and rather than mourning the object and letting it go incorporates it and treats it in an ambivalent fashion. This ambivalence often appears to take the form of self-denigration, but in the course of the Freud essay, as Schiesari notes, the melancholic becomes something of a heroic figure insofar as he, while appearing to castigate himself, actually speaks unwelcome truths about humanity at large.3 In an essay I published on Clint Eastwood as director/star/persona, I argue that he is a quintessential contemporary melancholic hero.4

As is the case with Clint Eastwood’s work, the melodramatic aspects of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights are often denied or downplayed. Speaking of Boogie Nights, the film that made Anderson a wunderkind in the cinematic world, Variety’s Emanuel Levy wrote, “Anderson’s strategy is remarkably nonjudgmental and nonsensationalistic.”5 Critic Andrew Sarris contended, “There is no dramatic or melodramatic closure to give the audience a warm glow of moral instruction.”6 Further, the film’s admirers implicitly endorse, if not its “will to political action,” at least its reliability as a document of the period: Roger Ebert praised Anderson as a “skilled reporter.”7 The San Francisco Chronicle enthused, “With Boogie Nights we know we’re not just watching episodes from disparate lives but a panorama of recent social history, rendered in bold, exuberant colors.”8

Of course, it is true that we must trust the tale, not the teller, but perhaps it is nevertheless somewhat instructive to note Anderson’s take on the relation of politics and “political action” to his portrayal of the social milieu in Boogie Nights. This would seem to be especially important in that the film appears to aspire to a kind of documentary truth, as evidenced in the titles the film uses to specify the dates of particular events, as the years pass and the 1970s’ sex, drug and disco highs merge into the violent and drug-addled lows of the 1980s. In an interview with Indie Wire Anderson says:

My take is that video is the real enemy there. I mean certainly drugs (were) a part of it, and I’m sure there’s sort of a bigger society picture, but that’s getting into the whole political arena…video is the enemy to me…the moment there was a chance for [the industry] to breathe and sort of open up and develop a new genre…it was sort of taken away by video tape. (Ellipses in original)9

Anderson’s dismissal of “the whole political arena,” “the bigger society picture,” is rather laughable in the face of the grandiose claims made for the film as one that conveys the period with accuracy. To whittle enemies of pornography down to one single villain—video—is to fly in the face of the ongoing history of pornography’s persecution and prosecution in the United States. Writing for Salon.com, Susie Bright, member of the sex-positive wing of the feminist movement, voiced outrage that the film neglects to even hint that the greatest enemies to pornography, both film and video porn, have been the moral and legal forces who have persistently hounded and jailed the purveyors of pornography.10 Indeed, the literature documenting the history of pornography overwhelms the reader with the sense of the constant harassment to which workers in pornography have been subjected. In this essay I attempt to document yet other elements, other so-called “enemies” to the world of 70s pornography, that Anderson leaves out of the historical record, and to show how historical suppression dovetails with psychic repression. Instead of history we are presented with melodrama. Instead of a historical document, the film gives us, again, Oedipus.

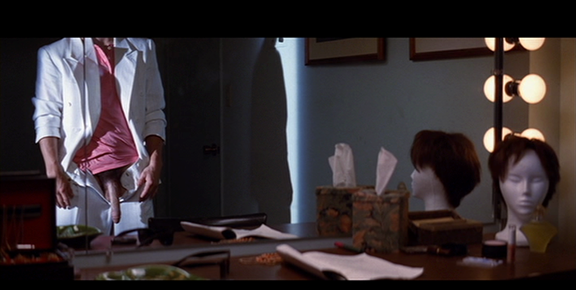

Exquisitely filmed in Altmanesque style and drawing on scenes from the films of Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino, as well as drawing on the sensibilities of these directors, Boogie Nights continues to this day to be proclaimed an ultra hip and daring look at the so-called Golden Age of pornography set in the disco-dancing, cocaine-sniffing era of the 1970s. It is an elegy to this age, as Anderson’s words, quoted above, suggest, and an aura of melancholia surrounds the film, even in its supposedly more comic moments. The film tells the story of a young man modeled after the famous and famously well-endowed porn star John Holmes, who made a number of films starring himself as a character named Johnnie Wadd, a name he embraced and that was thereafter frequently associated with his star persona. Eddie Adams is the child of a dominating mother and henpecked father who comes to realize he has one gift—a large penis—and with this gift he can make something of himself. This realization comes when pornographer Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds) spots him in a nightclub where Eddie is a waiter and somehow intuits what lies beneath Eddie’s belt.11 Soon after this night, Rollergirl (Heather Graham playing a young woman who never takes off her skates even when having sex) is sent in to fellate Eddie and report back to Horner, who convinces him that he has a promising future in the pornography business. Driven out of the house by his jealous mother, Eddie, who soon thinks up the name Dirk Diggler as his nom de porn, is warmly welcomed into Horner’s loving if dysfunctional family consisting of Horner as father, Rollergirl as sister, and Horner’s wife, porn star Amber Waves (Julianne Moore), who, having lost custody of her own son, welcomes Eddie as her surrogate son, a relationship she never tires of declaring.

In point of fact, the shadow of Oedipus hangs over the entire film. In one early scene Amber futilely attempts to get her son’s father to let her speak to her on the phone. While a sexy party is going on at Horner’s house, the telephone rings, and a man picks it up; the caller, we are led to believe, is the son calling for his mother, “Maggie.” As no one knows anyone named Maggie (and as Amber is busy sniffing cocaine) the boy is unable to make contact. In a way, Boogie Nights is one long cry for Mommy and Mommy’s reciprocal cry for her lost baby boy: the melodramatic scenario boiled down to its essence.

Eddie’s mother, who appears very briefly at the beginning of the film, is a jealous, bitter harridan whose anger at the thought that Eddie is fucking his girlfriend, causes her to fly into a rage, ripping posters off his bedroom wall, screaming that he is stupid and will never be anything but a loser. Meanwhile, we see his father in another room, engulfed by shadows, hanging his head and saying nothing. After escaping the maternal home, Eddie finds a new/old home when he and Amber have sex in front of the camera and Amber tells Eddie when he is about to climax that she wants him to come inside her. The San Francisco Chronicle reviewer applauds the scene: “Moore plays the scene as though welcoming her son back into the womb.”12 The bad mother, then, is the one who drives you out; the good mother is the one who invites you to come in(side of her). And of course, this all happens right in front of the approving father.

Hints of incest in the film notwithstanding, Anderson is surprisingly square for a man with such a hip reputation. His talent for turning “conventional morality on its head nonchalantly, almost sweetly” is overrated.13 Amber’s longing for her baby boy is as conventional as it gets. The film suggests that for all Amber’s sexual activity she remains unfulfilled, her only emotion a longing for her lost child. In this film “conventional morality” remains very much what it has always been for women. Further, although this might seem to be a case where a woman is portrayed as melancholic, I would argue that her melancholia, which actually seems more like depression (as Schiesari has said is usually the case with women), is a projection on the part of “the son,” who can’t get through to her.

In addition to the time-honored evil mother, the film features yet another “villain” in the form of an ancient stereotype: the cuckolding wife, a character who is one of the biggest ballbreakers in the history of American cinema (ironically played by porn star Nina Hartley, known for her feminist views and activities). Her husband, Little Bill, played by William Macy, continually encounters her while she is making love with another man. The first time he enters a room in his home where a man is taking her a tergo she looks up at him when he asks her what she’s doing and sneers, “What the fuck does it look like I’m doing? I’ve got a cock in my pussy, you idiot. Just get out, Bill. Fucking sleep on the couch. Keep going, big stud.” In the party scene, she is making love with a man in front of a group of onlookers, whom Little Bill joins, only to be told by his wife, who never skips a beat, to go away because he is “embarrassing” her. He slinks off. Little Bill catches her in the act one too many times, however, and he shoots his wife and sex partner and then blows his brains out. That this event occurs on New Years Eve, 1979, the precise moment Anderson identifies as the moment of the demise of the Golden Age of Pornography, when video presumably started coming into its own, is highly significant. But in order to understand the full import of the relationship between Little Bill and his wife and how it relates to the film’s historical repression of important aspects of the history of pornography, it is necessary to investigate further Anderson’s claim that video spelled the death of pornography as a legitimate Hollywood genre.

Little Bill blows his brains out after killing his wife and her sex partner

The advent of video in the early 1980s is seen to quash Horner’s hopes to direct great porn movies. The fictional Horner’s dismay when he is confronted with the necessity of turning to video is echoed by many erstwhile real-life pornographers, who deplore the advent of video and its takeover of the porn industry. It is certainly true that video at the very least hastened the death of pornographers’ “conceit that they were artists” and butchered some of the films that had achieved a certain level of legitimacy. As journalist and documentary filmmaker Michael Stabile puts it, “Remember, in the 70s you had movies like Behind the Green Door at Cannes. LA Plays Itself was shown at MoMA. The idea that Hollywood and the Valley [i.e. , the San Fernando Valley where most pornography was shot] would reach singularity, that Hollywood movies would begin to incorporate hardcore sex was central to the identity of a lot of these filmmakers. So mail order was really looked down upon.”14 On the other hand, Peter Lehman, who has written a trenchant article on Boogie Nights (which has otherwise, curiously enough, received scant scholarly attention), addresses the passage quoted above in the Indie Wire interview with Anderson and argues that “film styles and markets result from massive economic, social, and cultural forces which are complex and defy reduction to an ‘enemy. ’ The demise of 70s theatrical porn was as inevitable as the 60s demise of the old Hollywood studio system or the 90s demise of the European art cinema.”15

Lehman makes a convincing case that not all video porn has less craft, art, talent, and inspiration than film pornography. Lehman insists that a video porn auteur like Ed Powers made significant stylistic advances in cinematography and sound, as well as using broader ranges of human body types, especially female body types, and “displacing the oppressive domination of the meat shot.”16 For Lehman, Powers is every bit the auteur that the Mitchell Brothers or Alex de Renzey were. As we shall see, however, a great deal more can be said on behalf of video pornography and the kinds of sexual freedoms and diverse representations it offered, all of which are suppressed in Anderson’s work.

It is on New Year’s Eve 1979 that Jack Horner’s producer brings to Jack’s party a Mafia man who attempts to convince Jack to abandon film and his auteurist aspirations and move into video pornography. The transition from the golden age of the 1970s to the horrors to the 1980s occurs on a night when Eddie rebuffs the gay Scotty J. (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who drunkenly kisses him, and Little Bill shoots his wife and her lover. After Little Bill puts a bullet in his own head, the camera cuts to a white title against an all-black background that reads, “80s”—a time when Eddie gets too big for his britches, as it were, becomes addicted to cocaine, fails to launch a pitiful singing career, ends up being gay bashed when he takes a ride with a man who pretends to want to watch him jack off for money (which he is unable to do), and finally, like John Holmes himself, gets involved in a bizarre robbery scene that ends in multiple murders. Cross cutting in the gay bashing scene reveals Horner submitting to the ostensible imperatives of the video age, cruising in a limousine with Rollergirl, addressing the video cam and announcing that he is looking for an amateur to fuck a pro. The amateur they pick up turns out to be a former high school classmate of Rollergirl who had humiliated her in class by miming fellatio and causing her to leave during an exam; the scene turns ugly and first Horner and then Rollergirl beat the young man to a bloody pulp.

New Years Eve 1979 becomes the pivotal scene when all the “enemies” in Boogie Night’s Manichean drama come together, some more overtly than others. In what follows I attempt to unpack the dense psychic scapegoating that goes on at this crucial moment in the film and relate the over-determined phantasy of the film to the more complicated history of pornography and of real-life pornographers and porn stars in the 1970s and 1980s, especially in relation to women and gay men.

The transition from film to video increased women’s leverage within the industry. As film pornographer Henri Pachard remarks, “Women didn’t discover their power until video came along. Until then the power belonged to the director.”17 While numerous so-called “Stepford Sluts” populated the world of video porn, it was also the era of what came to be called the “video vixens,” of whom porn actress Ginger Lynn was considered to be queen. According to pornographer Bill Margold, “The three most important women in the business are Marilyn Chambers, Seka, and Ginger Lynn…They came along at exactly the right time. Chambers kicked it open with Green Door, then Seka transformed film into first-grade video—she was really the performer who carried the seventies into the eighties. Then Ginger picked up the ball and ran with it.”18 (It must be noted that John Holmes was an exception even in the golden age of porn in being paid more than female actresses, who were generally the major stars. )

Video not only empowered female porn actors, but as Jane Juffer argued some time ago, it also empowered female consumers of pornography who, understandably reluctant to enter the all-male world of porn theaters and porn shops, were able to put it to home use, as it were.19 Further, the greater access to pornography afforded by video arguably contributed to the reclamation in the 1980s of pornography by feminists, who in the 1970s had seen pornography as one of feminism’s chief enemies. “Pornography is the theory; rape is the practice,” Robin Morgan famously declared. In the early 1980s, feminist scholars began to question this bias and to insist on their rights to the pleasures offered by explicitly sexual representations.20

Most importantly, during the decade vilified by Anderson, a group of women who had performed in Golden Age pornography (among them Annie Sprinkle, Candida Royale, and Veronica Hart) began to form feminist groups to explore the question “Is there a feminist pornography?” In 1984 one of these women, Candida Royale, founded Femme Productions, which aimed to create pornography from a woman’s point of view. Susie Bright and several other female publishers founded On Our Backs, the first pornography magazine for lesbians, and a year later Fatale Video was created; its mission was to produce and distribute lesbian porn movies. Since then what Eric Schlosser calls “the new democracy of porn” ushered in by video has exploded.21 The recently published The Feminist Porn Book demonstrates how far women’s pornography has gone in creating entertainment not only for white heterosexual women and lesbians but also for women of color and trans women and trans men (the first of which was co-produced by Golden Age porn star Annie Sprinkle in 1990).22

The hideously misogynistic portrayal of Little Bill’s wife, murdered at the moment which ushered in the decade when feminists started claiming for themselves the right to enjoy pornographic representations as well as questioning the limits of heterosexual porn aimed at a male audience—the moment when video was coming into its own—can be phantasmatically viewed as a scapegoating of women for the demise of film pornography as it had existed in the past and as a reaction/overreaction to the empowerment of women in the industry and the actions of women to seize and to create access to sexual representations for their own pleasure.

That Little Bill is generally considered to have been loosely based on porn actor Cal Jammer (née Randy Layne Potes), who actually worked in the 1990s, not the 1970s, is telling. Cal Jammer, according to several porn directors, was not very successful in the industry (although his list of credits is quite long) and was obsessed with thoughts of his wife’s infidelity. Jammer’s wife, Jill Kelly’s story is somewhat different from the story fictionalized by Anderson. She, along with others on the scene, claimed that Jammer was exceedingly jealous of her even though when he met her he intended to promote her as a porn star. Kelly also says that, despite his obsession with her, he constantly cheated on her, always swearing to quit, but never able to do so. He continually threatened to kill himself and one day came over to her house and made good on the threat. Needless to say, perhaps, Jill was not making love with another man at the time.23

Anderson nicely captures Jammer’s/Little Bill’s anxieties about his position in the porn business. In Boogie Nights Little Bill is not an actor but works in the crew. Nevertheless, Jack keeps treating Little Bill like a nonentity, brushing off his attempts to talk to him about shooting schedules and the like. Further, when Eddie and Amber are having sex on the screen the camera moves in on the anguished face of Little Bill, conveying his insecurity about his own sexual prowess.

The real-life Jammer, according to pornographer Henri Pachard, was in fact suffering from a sexual identity crisis. As Pachard explains, Jammer was proud of his ability to do what in the industry are called DPs—double penetrations in which two men are able to fit their penises into one woman’s vagina or anus. Pachard’s colorful words are worth quoting at some length:

So these guys complain that they don’t get booked, but when it comes to DPs they do their own selling: “Let me tell you about the time me and this guy DP’d this girl!” And they’re not lying they probably were great. They got their dick in that girl’s ass, and they were wonderful at it—because it felt so good to run their dick against another guy’s dick, and they didn’t even know it.

I said, “I’m happy for you.” I tell them they could be out making gay movies.

He’d say I don’t do that.”

I’d say, “All Right.”

I mean, this is an identity crisis they’re in. They want me to feel sorry for them and give them money for their failures because they cannot accept their sexuality, and they’re half my age. What am I gonna do, guide them? “Son, it’s time you just accepted your proclivities . . .”

That’s not my job.

And further,

Cal liked feeling other guys’ dicks alongside his. What’s wrong with that? Is it such a bad thing that you feel you have to hide behind some stripper girlfriend who’s gonna dump you in a minute? Why would someone set themselves up to fall like that?24

What’s wrong with that indeed? One might ask the same of Boogie Nights, which, just as it scapegoats women, also scapegoats gay men, phobically denying homosexual possibility. As I have mentioned, at the New Year’s Eve party, on the same night when the man based on the closeted figure of Cal Jammer shoots his wife, the young Scotty J. , a nerdy insecure gay kid who has a huge crush on Eddie, kisses him, only to be slapped away. Scotty J. proceeds to sit in his car sobbing and repeatedly calling himself an idiot. He is a pathetic character throughout the film; after the kiss, we see him mostly in the background, especially pronounced in the scene where Diggler and Jack quarrel and nearly engage in fisticuffs; Scotty J. stands in the background looking horrified and holding his hands up to his mouth.

New Years Eve 1979: Eddie rebuffs Scotty J. , who has just kissed him

That the kissing scene and Little Bill’s murder of his wife and her lover both occur on that fateful night when video threatens to kill the porn film industry suggests that what is at stake, psychically, is a world in which straight white male film directors fear they are losing control of the dissemination and consumption of sexual representations. For if the empowerment of women in video pornography represents one threat, gay video porn represents another. The fantastic success of the biggest entrepreneur in the gay porn video market, Chuck Holmes, founder of Falcon Studios in San Francisco and major distributor of gay porn videos, is a case in point. According to Michael Stabile, who is in the process of making a documentary about Holmes titled “Seed Money”:

Chuck started in video in about 83 [the same year that Club 90 was founded by a group of feminists who were porn stars during the Golden Age]. He wasn’t a pioneer exactly—he believed in letting other people make the first mistakes, like Beta. During the Reagan recession, he bought up a lot of companies that had gone broke from the bad economy or obscenity prosecutions, so when video really took off he had a back catalog the size of MGM. That was really where he made his money.25

Most pornographers of heterosexual sex could only envy the success of Holmes.26

Moreover, just as women were granted greater access to video porn, so too were gay men avid consumers of gay male porn videos. According to Jeffrey Escoffier, “While many gay men took advantage of the porn theaters to engage in gay sex, there was an even larger audience of gay men more comfortable with viewing hardcore movies at home without risk of either police harassment or arrest.”27 Not only video’s “accessibility,” but its “versatility,” in the words of Robin Griffiths, contributed to the “new democracy of porn”: the 1990s saw greater representation in gay pornography of men of different ethnicities, ages and body types.28 It was in 1989 that major porn auteur Kristen Bjorn, released his first gay video feature, Tropical Heatwave,and he has continued to make pornography featuring men of varying ethnic backgrounds and nationalities.

Interestingly John Holmes, on whom Diggler is based, did perform in some gay porn both early and late in his careers. According to a recent biography of Holmes, a book composed mainly of interviews with people who knew him intimately:

During the Golden Age, it was not considered unusual for many sex performers to work on both sides of the fence during the preliminary stages and throughout their careers. John appeared to have respected and supported his gay and bisexual fan base throughout his career. His best-known feature that was intended for the homosexual market was made in 1983, The Private Pleasures of John Holmes.29

Boogie Nights is certainly far from showing respect to the gays and bisexuals that allegedly comprised part of Holmes’s fan base. Its homophobia is not only discernable in the care the film takes to distance Eddie from homosexual activity but in Anderson’s decision to suggest that Eddie is closing in on the nadir of his career when he becomes a street prostitute and is subjected to a “fag bashing” even though it has been made clear that he is most certainly not a “fag.” The gay bashing occurs at the point in the film when Eddie, after storming out of Horner’s world, becoming addicted to cocaine and failing to succeed at any other endeavor, allows himself to be picked up by a man who pretends he wants to watch him jerk off. A bunch of guys lying in wait then beat him up. The film’s bad faith is most in evidence here, as we liberals in the audience are made to loathe the “fag bashers” and yet feel sorry for Eddie, who is an “innocent”—i.e. , heterosexual—victim.30

Thus, the depiction in the film of events occurring in and following New Years Eve 1979, when everything supposedly went down the tubes, censors certain historical realities and replaces them with melodramatic scenes and character types that symptomatize the fears of straight white film pornographers whose powers were encroached upon by what the FBI would have called, ironically given the subject matter, “undesirable elements.” As the 1980s approach, all these elements seem to be oozing out and contaminating the closed, tight world of the heterosexual patriarchal pornotopia that has been depicted in the film.

Of course one of the biggest threats to the porn industry as it had developed in the 1970s was the AIDS epidemic, but Anderson stops short of even hinting at the devastation shortly to come (John Holmes would die of AIDS, after having knowingly infected numerous partners). Instead he again substitutes melodrama for history and politics: Eddie returns to the family fold and is shown crying on his substitute mommy’s lap.

The prodigal son returns and cries on his substitute mother’s lap

In his interview with Indie Wire, Anderson expressed disappointment that some viewers saw the ending as upbeat. Surely he is blind to his own text. It is true, as Anderson says, that the characters haven’t exactly learned anything, but are the same as they were at the beginning. Let us recall, however, that the beginning was full of fun and good times, though not without hints of the darkness to come. Likewise, the ending provides reason to hope. In keeping with the film’s strongly moralistic streak, the film metes out poetic justice to the producer who liked underage girls and is into kiddie porn: he is beaten in prison by his hulking black cellmate. Rollergirl, who has recruited Amber as a mother, has returned to school. The black man, Buck Swope (Don Cheadle), has profited from being in a convenience store when a robbery went down; he has opened his own store selling stereo equipment, fulfilling a life-long dream, after having failed to get a bank loan because he and his white wife have acted in porn. Buck and his wife have a baby boy. On the one hand, it could be said that the film’s liberal gesture of having the baby be the product of miscegenation is partly undercut by the fact that we never actually see the black and white characters involved in a porn scene. On the other hand, Anderson is perhaps to be commended for his avoidance of stereotypes of black men and their outsized penises.31 Buck, a man who loves country western music, seems to be looking for a place for himself in this world (at the New Year’s Eve party he is dressed ludicrously in Egyptian garb as he experiments with different identities he might assume).

Despite all of the hope proffered in the film’s conclusion, the final scene is at least somewhat ambivalent towards Eddie, as, in a scene reminiscent of the ending of Raging Bull, he sits in front of a mirror repeating, “I am a star. I am a star.” Is he, like Jake La Motta, washed up? What is the significance of his pulling his penis out of his pants? It is limp, on the one hand, but even limp it is huge. Anderson considers what we might call the film’s “meat shot” (usually a penis coming on a woman’s body or her mouth) a gift to the audience for having sat through a film in which we constantly wondered about Dirk Diggler’s legendary penis size. Peter Lehman felicitously calls the reveal a case of “the melodramatic penis,” invoking films like The Crying Game, another movie in which a shot of a penis is crucial to the film’s dynamic, and claiming that such films tell us more about sexuality in Anderson’s time than about sexuality in the seventies. For Lehman, the fact that the penis is flaccid does not, in this case, suggest a loss of phallic power:

This kind of emphasis on the large flaccid penis results from a slippage of the erect penis onto the flaccid penis. That is, if we are going to show the flaccid penis, it had better look as much like the supposed awesome spectacle of an erection as possible. Indeed, the flaccid penis in Boogie Nights seems virtually indistinguishable from the 13-inch erection we have been hearing about. And the brutally frontal, nearly confrontational manner in which the penis is directly revealed for the camera also relates the shot to melodrama’s excesses.32

Certainly the shot of the penis itself is melodramatic in its sudden bold appearance, but is it true that we remain in awe of it? The final scene of Eddie may recall the scene following his cocaine addiction when, in contrast to his ever-ready state early in the film, he has trouble getting an erection. Further, as Susan Bordo observes, “Despite its dimensions, Dirk Diggler’s penis is no masterful tool. It points downwards, weighted with expectation, with shame, looking tired and used.”33

The “money shot”

Or is the phallus in fact to be searched for elsewhere—say in Anderson’s style itself? Critics, even those who didn’t care much for the story, nevertheless express awe at the film’s style. In a sense, however, the style is closely linked to the substance, insofar as we may consider the substance to relate at least in part to the old penis/phallus debate. Eddie has a speech early in the film in which he opines that everybody has at least one special thing going for them; Eddie is convinced that his thing is a giant penis. That the penis in the last shot remains, strictly, a body part (as Judi Eddelston notes: “It is significant that we do not see Dirk’s head, only his penis; after all, when he started thinking for himself, he lost his head and spiraled down into a world of hustling, drugs, and crime”); that it thus carries none of the connotations of the phallus, certainly disqualifies its possessor as the phallic hero of, say, film noir (the genre of Anderson’s first film Hard Eight).34 Jack Horner, as producer of the Diggler films, seems to come closer to phallic power but falls short at those times that Anderson appears to mock him, for example, by giving him a speech in which he tells of his dream of making great art (although, as we have seen, Anderson himself deplores the loss of pornography’s potential to be if not great art, then at least a “legitimate genre”).

Ultimately, I submit, the phallus lies in the film’s cinematic technique and in the continual reminders that the person behind the camera has complete mastery of his craft and of the world he has created. Three shots illustrate my point.

The first is the film’s vaunted opening shot, an extremely long take in which the camera begins with a marquee-like title, “Boogie Nights,” moving up to a sign reading “Reseda” and then panning and craning down to show a car pulling up to a disco club, Traxx; Amber and Jack step out of the car and greet the owner, Maurice TT Rodriguez (Luis Guzman) who shows them to a table. Throughout, the camera moves fluidly among the patrons and dancers, and we are given a first glimpse of many of the secondary characters. Amber and Jack sit at a table, to which cocktail waitress Rollergirl glides up and then away. Eventually the camera pans around to a shot of Eddie. At that point we have the film’s first cut as Jack catches a glimpse of Eddie, and the camera moves in for a close-up of the former’s fascinated gaze. There is no doubt that the camera is the real star here, announcing itself emphatically at the outset, capturing the world it proceeds to “document” in a style that draws attention to itself more than to any individuals within the film’s diegesis.

While Anderson employs long takes throughout the movie, one of the two other longest ones occurs during the New Years Eve party when Little Bill shoots his wife; the second of these occurs at the end in the film’s penultimate shot (the one preceding the shot of Eddie in front of the mirror talking to himself and then revealing his penis to the avid film audience). The first of these shots shows Little Bill arriving at the party, coming into the house and walking through the throng of party-goers searching for his wife. The camera continues down a hallway losing sight of Little Bill who passes behind a wall into the kitchen only to reappear and come back into the hall, at the end of which he opens a door to see his wife (off camera) again having sex with someone. The camera then follows Little Bill back down the hallway and out into the night; he opens his car door, sits down, gets a gun and loads it, and then goes back into the house and down the hallway, opens the door and shoots the gun several times. At last there is a cut to the startled party-goers and then another cut to Little Bill emerging into a close-up and blowing his brains out.

That Anderson chooses to shoot this in a single take approximately three minutes in length—no cuts until Little Bill has murdered his wife and lover and is about to cut off his own life—suggests that the camera is functioning apotropaically to ward off the threat of castration that Little Bill has represented throughout, having been cuckolded in the most humiliating way possible. Anderson’s penetrating, virtuoso camerawork with its long, long takes of a man whose very name suggests that he possesses a little, little dick and who is desperately avenging himself on his cuckolders shows us in no uncertain terms to whom the phallus belongs.

The third of the three lengthy takes occurs at the end of the film and, like the opening shot, brings together most of the film’s dramatis personae. The camera tracks Jack Horner, as he watches some men unload equipment from a truck and then moves through the house, encountering several of the “family” as he does so; he goes out to the patio where Buck’s baby is being dangled in the pool by Eddie’s sidekick Reed Rothchild (John C. Reilly), reenters the house, passes Buck, walks down the hallway where a portrait of Little Bill is hanging on the wall, the same hallway Little Bill once trod on his mission to kill his wife, and goes into the bedroom where Amber sits in front of a mirror. Jack calls her “the foxiest bitch in the whole world.” He seems to be back in control of his empire. Here, both directors, the fictional Horner and Paul Thomas Anderson, lamenters each for the demise of film pornography as a legitimate genre, merge. Nineteenth century melodramatic dictates are in the end fully obeyed, as a disruption to an initially harmonious family throws it into tumult but is overcome and the family is reunited once more, with the white patriarch fully in place.

Like most elegies, Boogie Nights reveals that the subject being elegized is less important than the elegizer himself. Further, as in many elegies, the negative or undesirable aspects of the subject are minimized or omitted, although as I have tried to show, they come back to haunt the text. Instead, the film’s sentimental conclusion (the prodigal son returning, embracing the “father,” weeping on his “mother’s” lap; the birth of a baby boy in a racially harmonious world; etc. , etc. ) provides the “consolation” that comprises the typical ending of the elegy as a poetic form, a consolation that in the case of Boogie Nights flies in the face of history and its assaults on hetero-masculine sexual privilege.

Notes

Tania Modleski is Florence R. Scott Professor of English at the University of Southern California. She is the author of Loving with a Vengeance: Mass Produced Fantasies for Women, 2nd edition (New York and London: Routledge, 2008), The Women Who Knew Too Much (New York and London: Routledge, 2005), Old Wives Tales and Other Women’s Stories (New York: NYU Press, 1998), and Feminism without Women: Culture and Criticism in a “Post-feminist” Age (New York and London: Routlege, 1991), in addition to numerous essays.

Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 55.

Juliana Schiesari, The Gendering of Melancholia: Feminism, Psychoanalysis and the Symbolics of Loss in Renaissance Literature (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992), 16.

Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works, ed. and trans. James Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1943-1974), 243-258.

Tania Modleski, “Clint Eastwood and Male Weepies,” ALH 22, no. 1 (2010): 336-358.

Emanuel Levy, “Review Boogie Nights,” Variety. Retrieved from http://variety.com/1997/film/reviews/boogie-nights-1117329514/ 23 May 2013.

Andrew Sarris, “Before Videotape Killed the Artistry of the Porno Flick,” New York Observer (October 20, 1997). Retrieved from http://observer.com/1997/10/before-videotape-killed-the-artistry-of-the-porno-flick/ March 26, 2013.

Roger Ebert, “Boogie Nights,” Chicago Sun-Times (October 17, 1997). Retrieved from http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19971017/REVIEWS/710170301 March 26, 2013.

Mick LaSalle, “‘Boogie’ ManDoes the ‘70s/Mark Wahlberg is a porn star in film that catches spirit of an era,” San Francisco Chronicle (October 17, 1997). Retrieved from http://www.sfgate.com/movies/article/Boogie-Man-Does-the-70s-Mark-Wahlberg-is-a-2825519.php March 26, 2013.

Mark Rabinowitz, “An Interview with Paul Thomas Anderson, Director of Boogie Nights,” Indie Wire (October 31, 1997). Retrieved from http://www.indiewire.com/article/an_interview_with_paul_thomas_anderson_director_of_boogie_nights. March 26, 2013.

Susie Bright, “Boogie Nights Bummer: How the Movie Got the Porn Business All Wrong,” Salon.com (October 25, 1997). Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/1997/10/25/nc_24boogie/ March 26, 2013.

For an interesting discussion of the homoeroticism between the two men, see Brian Michael Goss, “’Things Like This Don’t Just Happen’: Ideology and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Hard Eight, Boogie Nights, and Magnolia,” Journal of Communication Inquiry 26, no. 2 (April 2002): 184-185. Retrieved from http://jci.sagepub.com/26/2/171 March 26, 2013.

LaSalle, op. cite.

Charles Taylor, “Boogie Nights,” Salon.com (October 27, 1997). Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/1997/10/17/boogie/ March 26, 2013.

Michael Stabile, personal email communication, November 19, 2012. I am grateful to Michael for so generously sharing with me his knowledge and insights into the porn industry. Any mistakes I make in my discussion of the history of film and video pornography remain strictly my own.

Peter Lehman, “Boogie Nights: Will the Real Dirk Diggler Please Stand Up?” Jump Cut (December 1998): 35. Retrieved from http://zb5lh7ed7a.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.882004&ctx_enc=info%3Aofi%2Fenc%3AUTF8&rfr_id=info:sid/summon.serialssolutions. com&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:journal&rft.genrearticle&rft.atitle=%22Boogie+Nights%3A%22+Will+the+Real+Dirk+Diggler +Please+Stand+Up %3F&rft.jtitle=Jump+Cut&rft.au=Lehman%2C+Peter&rft.date=1998-12-01& rft.pub=Jump+Cut+Associates&rft.issn=01465546&rft.spage=32&rft. epage=38 26 March 26, 2013.

Lehman, 36.

Quoted in Legs McNeil and Jennifer Osborne, The Other Hollywood: The Uncensored Oral History of the Porn Film Industry (New York: Regan Books, 2005), 366.

Quoted in McNeil and Osborne, 367.

Jane Juffer, At Home with Pornography: Women, Sex, and Everyday Life (New York: NYU Press, 1998).

The first collection of scholarly essays was compiled from a conference, “The Scholar and the Feminist IX” held at Barnard College in 1982. Its theme was female sexuality, and it is widely credited with having begun “the feminist sex wars.” See Carole Vance, Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality (New York: Routledge, 1984).

Eric Schlosser, Reefer Madness: Sex Drugs, and Cheap Labor in the American Black Market (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2003),166.

Tristan Taormino et al. The Feminist Porn Book: The Politics of Producing Pleasure (New York: The Feminist Press, 2012). The introduction provides a concise overview of the history of feminism’s vexed relation to pornography and of the developments in women’s pornography since the early 80s. Its information has proved useful in the writing of this article. For a book that contains a great many of the most important essays written since the 1970s (up to 2000) on women and pornography, see Drucilla Cornell, ed. Feminism and Pornography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000). A book that one cannot fail to mention when talking about the history of feminism and pornography is Linda Williams’s influential Hardcore: Power, Pleasure, and the Frenzy of the Visible (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989). In this book, Williams is interested in teasing out the contradictions in the depiction of pornography that is aimed at a heterosexual male audience; she doesn’t extensively discuss women’s investments in explicit sexual representations. In a later work, however, which looks at sexuality in the movies beyond hardcore pornography (in, for example, art films and the avant-garde films of Andy Warhol), she discusses her own relation to sex on the screen. See Linda Williams, Screening Sex (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008).

McNeil and Osborne 545-550.

Quoted in McNeill and Osborne 544, 547.

Stabile, personal email communication, November 19, 2012.

Major exceptions include Reuben Sturman and Phil Harvey, the latter of whom was a philanthropist like Chuck Holmes. For a discussion of the colorful life of Sturman, his empire building, his links to the Mafia, his prosecutions, incarceration, prison escapes, etc. , see Schlosser 116-208. Schlosser’s discussion of Harvey may be found on pages 185-93.

Jeffrey Escoffier, Bigger Than Life: The History of Gay Porn Cinema from Beefcake to Hardcore (Philadelphia: Running Press, 2008), 177.

Robin Griffiths, “Porn Star” in Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer Culture, ed. David A. Gerstner (New York: Routledge, 2006), 459.

Jennifer Sugar, Jill C. Nelson and William Margold, John Holmes: A Life Measured in Inches, second edition(Albany, Georgia: Bear Manor Media, 2011). Despite the unfortunate title, the book is serious and informative. See also the documentary directed by Cass Paley, WADD: The Life and Times of John Holmes, 1998. In addition to The Private Pleasures of John Holmes, early films of Holmes include “Pool Film” and “Big Deal,” according to Stabile, who also notes that Holmes seems to have been a “pretty active escort.” Private email communication, November 14, 2012. In contrast to the Holmes’ biographers’ assertion that straight performers worked both sides of the fence throughout the 1970s and 1980s, both Jeffrey Escoffier and Robin Griffiths maintain that it wasn’t until the mid 1980s that many straight men began in significant numbers to perform in gay pornography. See Escoffier, “Gay-for-Pay: Straight Men and the Making of Gay Pornography,” Qualitative Sociology 26, no. 4 (Winter 2003): 531-555. Escoffier offers interesting observations on the contradictions and paradoxes of this form of “situational homosexuality” as they relate to both straight actors and gay audiences.

Goss argues that Eddie is being punished for his foray into homosexuality: “As [Eddie] awaits a john, the camera captures [him] in silhouette at night; a glowing Christian cross on a church across the street is the most visually striking aspect of the frame’s composition and furnishes a hint that moralistic judgment is in store.” Thus it is probably most accurate to say that Eddie is in fact punished for allowing himself to be picked up, but that nevertheless there is a strong element of pathos elicited by this scene, since we know Eddie is not “really” gay. 184

It is possible that Buck is modeled on Johnny Keyes, the black male costar of Behind the Green Door, a man who made about 50 movies in the 70s and 80s. Speaking of Behind the Green Door, Natalie Purcell remarks that the film “both relies on and deploys the black man as savage sexual animal, with special endowments and special sexual prowess inherent in his biological makeup.” Violence and the Pornographic Imaginary: The Politics of Sex, Gender and Aggression in Hardcore Pornography (New York: Routledge, 2012), 65.For a hair-raisingly graphic description provided by Keyes who explains how fucking Marilyn Chambers felt like revenge for black slavery see McNeill and Osborne 93. And for an interesting and eye-opening discussion of the “fixed” patterns of interracial sex in both straight and gay porn, see Daniel Bernardi, “Interracial Joysticks: Pornography’s Web of Racist Attractions,” in Pornography: Film and Culture, ed. Peter Lehman(New York: Routledge, 2006) 220-243. Print. Bernardi’s essay is in part a response to Linda Williams’s utopian readings of films like Behind the Green Door. Williams’ analysis of the film doesn’t analyze the film’s interracial dynamics. Don Cheadle’s character, whose identity is in flux, can thus be seen as a refreshing change from the fixed nature of raced representations in heterosexual pornography aimed at white men. Thanks to Dana Johnson for her insight on this aspect of the film.

Lehman 37.

Quoted in Nicola Rehling, Extra-Ordinary Men: White Heterosexual Masculinity in Contemporary Popular Cinema (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009), 97.

Judi Eddelston, “Doing the Full Monty with Dirk and Jane: Using the Phallus to Validate Marginalized Masculinities,” Journal of Men’s Studies 7, no. 3 (1999): 346.