Circuit City Unplugged

Jeffrey Sconce

The entertainment industry is an industry—nothing could be more obvious than that. Somewhere out there, suits debate if the market will bear another Will Ferrell sports parody, advertisers conspire to convince us that deleted scenes from Hancock actually constitute a “bonus feature,” and retailers search for new ways to liquidate extra copies of another failed Dane Cook project. And yet, while we may be vaguely aware that budgeting, marketing, demographics, advertising, and distribution have an impact on media commodities, the business side of entertainment often remains remote and almost magical—like Keebler elves shoveling cookies out of a tree.

There are, however, occasions when a radical irruption forces a more direct and all-too-real confrontation between the economic realms of production and consumption, Fudge Stripe factory and cookie jar. I experienced just such a breach a few days ago while having my car’s oil changed at the local Jiffy Lube. With a half-hour to kill, I decided to check out a “store closing” sale at the Circuit City across the street. For those who haven’t heard, Circuit City—once the nation’s second-largest retailer of media and electronics—recently declared bankruptcy, bested by Best Buy. While a few of the flagship stores will remain open, most Circuit City locations are in the midst of liquidating inventory and closing their doors for good.

I can’t say Circuit City’s troubles came as a complete surprise. Best Buy has clearly done a better job staging the fantasies of electronics consumption. With its solar-yellow-on-deep-blue signage, 40-foot ceilings, and faux-warehouse plentitude, Best Buy has become the Church of Convergence within the Big Box empire. A typical Circuit City, on the other hand, almost always looks like the forgotten floor of an insolvent J.C. Penny’s. While Best Buy’s choreography invites us to follow Hannah Montana, T-Pain, and the Cloverfield monster as they leap from platform to platform in a type of digital transubstantiation, Circuit City’s sagging acoustic tiles and rust-colored carpeting make even the hardware look sad to be there.

Yes, Circuit City was always a rather depressing destination, usually of last resort, and I doubt they will be missed all that much. Still, their bankruptcy should be cause for great concern. The chain’s collapse may seem little more than another casualty of the current “economic meltdown,” but the symbolic implications of Circuit City’s bankruptcy are much more profound than its material impact on the economy. As is generally well known, Americans gave up long ago on the idea that the nation would ever again manufacture any durable goods or useful commodities. In this respect, the impending collapse of Ford, GM, and Chrysler evokes not so much shock as a sense of nostalgic surprise (“They’re still making Chryslers…Who knew?”). After losing its manufacturing base, the nation’s one consolation was to dominate the globe in the production and consumption of media. Even if the U.S. no longer made the actual hardware, there was still some satisfaction to be had in leading the world in the production of crappy movies, raw television feed, and “Mentos meets Diet Pepsi” You Tube postings. If an American retailer can now go broke selling electronics and entertainment—to fellow Americans, no less—then perhaps the end really is near.

These thoughts weighed heavily on my mind as I entered the store. Passing through a gauntlet of grimly enthusiastic “Store Closing” signs, I was immediately seized with that strange sense of embarrassment and shame that hovers over a bankrupt space—embarrassment for the merchant’s failure at capitalism and shame for one’s own opportunistic pillaging of retail misfortune. Of course, there is no rational reason for this awkwardness—most retail employees are wage-slaves with no real emotional investment in their particular brick and mortar outposts. Still, I found myself avoiding eye contact with the staff. Once the fixtures start coming down and the Styrofoam peanuts on the floor remain upswept, bankrupt spaces take on a feral quality. It is the tipping point between the obvious and the obscene, that moment when the niceties of consumer ritual fall away and leave only a brutally visible circuit of exchange: my money for your products. Don’t look at me while I shop! With no restocking, no rain checks, no tomorrow, each item becomes a wounded gazelle waiting to be picked off as shoppers move through the space either as fearless, informed hunters—demanding the last plasma screen be unbolted from the display wall—or as opportunistic vultures hovering at the edges of the herd, grateful to find even a stray iPod cover on the floor behind an abandoned display case.

Cautiously circling the store with my own mental shopping list, I found that most sections still had some vestigial product left on display—with one key exception. The gaming aisle was an absolute wasteland. Whether this speaks to the rarity or expense of Xbox product I cannot say. But this section’s utter decimation did resolve a series of perplexing questions. How did Max Payne make it to the screen? For that matter, how did not one, not two, but three Resident Evil movies clog up the nation’s multiplexes? Just what are fourteen-year-olds doing to kill the forty to fifty seconds of time before their next text message arrives? In the first Depression, mythology has it that Hollywood provided the great means of escape that kept the nation sane (nothing blunts the pain of poverty, after all, like watching showgirls dressed as filthy lucre singing, “We’re in the Money”). As the gaming industry increasingly makes the cinema a secondary platform, however, it appears that the next Depression (or, perhaps, this Depression) will be spent roaming the streets of Liberty City in search of virtual Ferraris to boost. In the interests of verisimilitude, perhaps game designers can add a soup line or a blind man selling pencils as additional driving hazards.

Next to the gaming section I found a rack stocked with Atomic Fireballs, Twix, Skittles, and other Technicolor candies, standing next to a refrigerator case chock full of Pepsi, Mountain Dew, and Rock Star Energy Fluid. The name “Circuit City” implies a trade limited strictly to electronics, so at first such fare might seem out of place. But in truth, here was the fuel necessary to keep the human remainder of the Xbox cyborg in an optimum state of chemical agitation and free-floating dementia. Perhaps out of sarcasm, this caloric juggernaut of corn syrup and chilled methylxanthines had been labeled as “Food”—10% off.

At the center of the store, meanwhile, employees had begun the melancholy task of dismantling the Guitar Hero display, no doubt to cannibalize the game, monitor, and couch for additional inventory. Here was a loss for the neighborhood that went beyond mere merchandise. Back in the days when Americans were in a more ambitious frame of mind, teenagers sometimes dropped out of high school to give more attention to their band or rap careers. Of late, however, it seems that more and more kids have been cutting school to work on their Guitar Hero chops, an apprenticeship that often brings them to Circuit City and Best Buy for prolonged muscle-memory “jam” sessions. Those searching for a symbol of America’s tragic destiny—a nation laid low by its excessive fascination with media, fame, and carbohydrates—need look no further than this: obese fourteen-year-old boys parked in EZ-Boy recliners at 2pm on a school day, joylessly riffing their way through Aerosmith’s “Sweet Emotion.” And nary a truant officer in sight! Still, sad as they were, Guitar Hero displays provided at least some remnant of public space for bored, wayward, and/or unimaginative teens. With this prime venue now removed from the tour schedule, those kids are probably back at home—denied the benefits of a daily walk to Circuit City—getting fatter and lonelier and thus more vulnerable to the flattering attention of Face Book stalkers. Either that or they are all Best Buy’s problem now.

I next visited ye olde “Compact Disc” section in the hopes that some esoteric boxed-set of interest to the 40+ crowd might still be on the racks. Unfortunately, not much was left—just the remnants of a former manager’s insane optimism as to how many Avril Lavigne or Nickelback units the store might have moved back when music still assumed some material form. Particularly sad was a nearly empty CD rack near the checkout area. Here were the orphaned discs that customers had pulled from the racks, presumably with an intention to purchase, only to banish them at the last moment as worthless even with a 20% discount. Mostly they were the kind of product K-Tel used to hock with such success during the vinyl age—cheaply licensed compilations of off-brand pop, funk, soul, and country hits. Customers apparently had done the math while standing in line: Ten “New Wave” classics of the 80s for $5.98…marked down to $4.78 on sale…that’s just under 50 cents per classic…Is Thomas Dolby’s “She Blinded Me with Science” worth 50 cents?…back on the rack it goes.

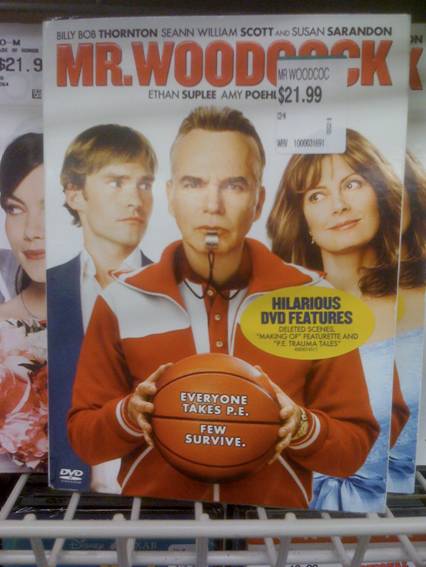

I was almost feeling sorry for Circuit City, this once thriving metropolis buried beneath a Pompeii blast of Wall Street greed, bad mortgages, and bottomless credit debt. But then I hit the DVD section. There on the shelf, stacked five deep, was the 2007 “comedy” Mr. Woodcock. Now, as it so happens, I have actually seen Mr. Woodcock. Laid up on the couch one night with the flu, too sick and too dispirited to change the channel, I allowed this fever dream of dick jokes to unfold without comment or laughter. The film stars Seann William Scott as a 20-something self-help guru who returns to his hometown in rural Nebraska. To his surprise and horror, he finds that his widowed mother (played by Susan Sarandon) is in a relationship with his former gym teacher (the eponymous Woodcock, played by Billy Bob Thornton). As one would expect, Woodcock is a total dick, a dick’s dick really, who has traumatized generations of young boys through his sadistic torment of the athletically challenged—be they fat, lazy, stupid, sensitive, or just slightly eccentric. Of course, even though the son is now successful as a nationally recognized author, he instantly regresses to the shame and loathing that marked his former relationship with Woodcock. Life, as it turns out, really is about who has the upper-body strength to climb the rope in gym class and who does not. Worse yet, the son must endure a predictable and increasingly tiresome series of comic set-pieces: hearing his mother and Woodcock engaged in raucous intercourse; seeing his nemesis walking around the family home nude and rude; listening to unsolicited testimonials as to Woodcock’s incredible sexual prowess. In the end, after an inevitable and less than sublimated showdown, son and gym fascist realize they share a common interest in Mom’s happiness. Moreover, the son comes to understand that Woodcock’s “tough love” made him the successful writer he is today. A new and better family emerges. In short, the movie embodies all the horrors that attend screenwriters actually reading Freud rather than simply letting their unexamined Oedipal difficulties emerge the old-fashioned way.

Recycled dick jokes are bad enough, but when they are served up under a meta-winking title like Mr. Woodcock they become particularly insufferable. And how much did Circuit City want for Mr. Woodcock? Incredibly, they were asking $21.99. Twenty-one freakin’ dollars and ninety-nine cents. True, with a 20% discount, the final price came out to around $17.50—still, that’s the better part of two sawbucks to relive the hilarious groin endangerment scenarios that accompany an adolescent boy’s first forays into wrestling, dodge ball, and jock strap adjustment. And this for a movie that did little to no initial box office and had already played for months on HBO. To put this in perspective, I later saw copies of Nacho Libre, Good Luck Chuck, and Meet the Fockers—all equally miserable in their own way– selling at a 7-11 for $5.99. So truly, the makers of Mr. Woodcock have oaken balls to be asking $21.99. With a running time of just under an hour and a half, this ode to dingus anxiety prices out around 25 cents a minute. From this perspective, the movie becomes like a swear jar—one that demands I throw away another quarter for each insipid gag I consent to witness. The price per minute comes down somewhat if the purchaser also watches the added DVD featurette, Pick up the Pace: Making Mr. Woodcock—but somehow this seems less a “bonus” than salt in the wound.

Looking at these “units” gathering dust on the shelf, brazenly overpriced at $21.99, I couldn’t help but see the film’s entire lifecycle pass before my eyes (and why not? Seeing the movie had been akin to a type of death only a few months earlier). I could visualize a committee of script doctors work-shopping their worst memories of junior high school—interns fetching lattes—the laser printer spitting out the finished script—agents on phones—checks being signed—equipment loaded on trucks at 4am for a 6am call—extras standing around the honey-wagon eating tofu wraps and lentils—a newly minted film school grad shooting B-roll in the closest town to L.A. that might pass for Nebraska–Foley artists searching for the perfect squeak of Converse on gym floor—editors taking a cigarette break, gathering the nerve to put the finishing touches on the crucial baseball bat to crotch sequence—rushes, color timing, test screenings—the graphics department high-fiving each other over the money shot of Thornton standing erect and holding two testicular basketballs side by side—distribution deals and exhibition scheduling—bored projectionists yawning and flipping the switch for the early Woodcock matinee—digital transfers—HBO traffic management—a foreign factory speeding blank DVD’s down the line for Woodcock encoding—crates of Woodcock DVDs arriving at Circuit City’s central distribution center—five DVDs thrown in the box for the northside Chicago location—an employee cutting open the box, pricing them, and then placing them on display. And there one such DVD sat, holding this paper-thin wisp of a movie backed by millions and millions of dollars in production, advertising, and distribution costs, hoping upon hope that at least five more people in the neighborhood would pony up the $21.99 to take Mr. Woodcock home—perhaps for a permanent collection of some kind.

How much should Mr. Woodcock cost? That’s hard to say, given how enchanted use and exchange value now seem in the twenty-first century—especially when considered in relation to the purchase of purportedly affective experiences. DVDs are a strange commodity in this respect. It is not difficult to understand the difference in price between a bottle of Chateau Lafite and a gallon of Mad Dog 20/20—so how is it that Mr. Woodcock prices out higher than a four-disc Don Knotts collection? But I digress. The shock here was not that Mr. Woodcock was priced too high, but rather that Mr. Woodcock exists at all, at any price. Again, if Depression-era Hollywood produced films as an escape, a place of temporary retreat from the troubles of the world, now there seems to be no escape in kind from movies themselves—droves and droves of pointless, uninspired, banal, and worst of all, completely average movies, titles multiplying independently of any perceived need or demand for them. Conjured into existence by some occult negotiation of financing, creative compromise, synergistic momentum, and occasional sexual favors, they queue up on the distribution runway for their chance at a fortnight of annoyance—demanding our attention in pre-release advertising, multimedia tie-ins, assorted talk-show plugs, vapid web chatter, and countless “consumer guide” reviews–snarky and straight, amateur and professional. And then the cycle repeats itself all over again for the DVD release! No doubt this is effective marketing, and perhaps this is what it takes to squeeze blood out of a Woodcock turnip. During the heyday of the studio system, Hollywood could afford a string of turkeys: they had a captive audience and generally covered their production costs up front. But the contemporary entertainment industry depends more and more on DVD and cable sales, the “secondary markets” that increasingly wag the dog of theatrical exhibition. In truth, the makers of Mr. Woodcock may not even care all that much if the film underperforms on opening weekend, just as long as the preparatory media campaign clears some brush in the public mind, a campsite where Woodcock can wait it out to re-emerge, hat in hand, for the DVD release.

There is surely a sense of panic attending these promotional carousel rides, as if the audience for all Hollywood product might evaporate unless every film—no matter how horrible—received an equal roll-out, the same blitzkrieg of bullshit to prop up a marketplace that is perhaps fatally flawed. America’s financial institutions recently collapsed, in large part, because of a similarly daredevil leveraging of capital—banks and insurers trading ever-escalating amounts of virtual money left wholly unsecured by equivalent assets. The whole house of cards of course began to implode once the loans were called in, the assets more fairly valued, and the fundamentals of the marketplace more soberly reassessed. Perhaps the entertainment industry senses the potential for a similar collapse in their own capital markets—the economic bottom line, to be sure, but also a more ineffable trade in cultural, symbolic, and affective capital, the world of buzz, attention, and a generally unexamined investment in consuming media for the sake of consuming media. The industry’s almost manic over-production of the banal would then make more sense. Like crazed mortgage bundlers, they too hope to make one last killing before their audience realizes that dick jokes have now been leveraged 40 to 1, that there is no “there” there backing up a rapidly expanding portfolio of CGI super slow-mo bullet films, or that the high-profile A-list treatment of Jim Carrey’s career ceased making sense a decade ago.

In the larger scheme of the marketplace, there was a time when you could still hear a few cranks arguing for a return to the “gold standard.” I don’t think any credible economists remain out there today to argue that this is feasible or even desirable. Still, the idea of abstract economies underwritten by actual bricks of metal stashed in a vault somewhere does raise interesting questions of value and asset, security and investment, in the realm of entertainment commodities. What would be the “gold” in a gold standard of entertainment, if such a thing could be imagined? As Xbox, Wii, and Playstation continue to marginalize popular cinema, will we soon discover that Hollywood has been living for decades on the declining interest from its squandered creative principle? On display amid the entropic ruins of a bankrupt Circuit City, Mr. Woodcock never looked so naked, obvious, obscene, and unappealing—a harbinger, perhaps, of a signifying order that will soon need its own New Deal, or at the very least an emergency injection of some indefinable form of “capital” to restore a degree of creative liquidity. After all, if the nation can no longer pretend to have money, how long can it continue to pretend to be entertained?

Notes

Jeffrey Sconce is associate professor in the Screen Cultures program at Northwestern University. He is the author of Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Durham: Duke, 2000) and the editor of Sleaze Artists: Cinema at the Margins of Taste, Style, and Financing (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007). His current book project, Delusional Media, presents a history of media and psychosis.